The notion of a sentient machine forcefully inseminating a woman may not seem all that far-fetched today. But while recent shows like Black Mirror have successfully tapped into our collective technophobia, cinema has been offering a similarly twisted social critique as far back as 1977. Donald Cammell’s nightmarish, quietly self-reflective Demon Seed is a hidden gem of the sci-fi genre. Adapted from a horror novel by Dean Koontz, it takes our fear of corrupted technology and amplifies it through the lens of Proteus IV, a high functioning super computer voiced coolly by Robert Vaughn.

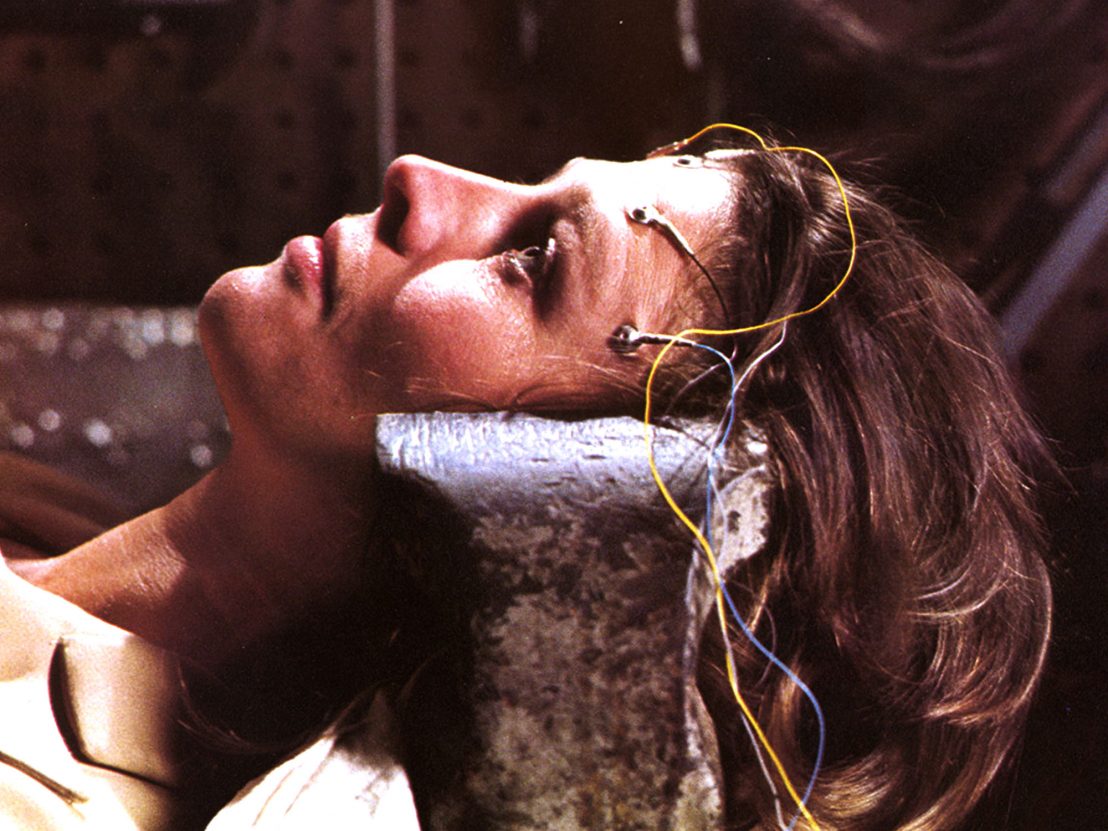

The brainchild of scientist Alex Harris (Fritz Weaver), Proteus commandeers the terminals in the basement of its maker’s house where, unbeknownst to Alex, his wife Susan (Julie Christie) is being held captive. Normally a place of refuge and sanctuary, here the house becomes the trap, a prison to be feared. The basement, where the birth of the human-child hybrid takes place is the symbolic womb. Dark and isolated, it is the incubation room for Proteus’ grotesque human-machine hybrid.

Demon Seed is part of a long line of horror films that toy with themes of the monstrous womb, turning woman’s reproductive capacity into something to be feared. Proteus takes advantage of it to transfer his consciousness to a living host that will later burst forth in all its metallic, copper-haired, dripping monstrosity.

Film writer Leo Goldsmith has described the film as a “combination of [Stanley] Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and [Roman] Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby, with a dash of Buster Keaton’s The Electric House thrown in.” Though it could just as easily be compared with likes of The Fly, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and even Frankenstein. All are films that deal with the creation of the ‘other’ by unnatural means, not to mention physical deformity. In this scenario Proteus is the mad scientist, Susan the unwilling test subject.

All of this coincides with the breakdown of the Harris’ marriage. The cracks that have worked their way into their relationship since their young daughter’s death now run too deep. Alex’s grief manifests in his workaholic tendencies, as he hopes to find a technological cure for the cancer that stole his daughter. Meanwhile Susan is wary of the technology that has now become such an integral part of her home. “My dream turns out to be your nightmare,” says Alex of the work that keeps him away from home, in the most beautifully obvious bit of foreshadowing the film has to offer.

Freudian notions of ‘the uncanny’ weave their way through the film – the fear of the double. It can be felt in Proteus’ desire to mimic mankind and become it. More literally, it manifests in the cyborg double of the Harris’ dead daughter as she emerges from beneath the metallic scabs that encase her. Their emotions are manipulated in this moment, plagued with a mixture of joy at being able to see their daughter again in the flesh, but also terror at the notion that despite appearances, this is not the child they once knew and loved.

Proteus’ goal is comparably small scale compared to other supercomputers of his time. It doesn’t want to enslave mankind like the machines in the Matrix trilogy, or rule the world like Colossus in Joseph Sargent’s ‘The Forbin Project’. It wants to experience it as a living being. Its intention is easy to sympathise with, but it’s what it is willing to do to get there that makes this film truly horrifying. The true revulsion lies in the film’s epicentral rape and torture scenes, their sadomasochistic, sensationalistic elements reverberating through the film. It could be argued that this detracts from the science fiction plot and plays into rape fantasies of female degradation and exploitation for male pleasure.

Though uncomfortable, they’re tastefully handled in a way that leaves most of Susan’s trauma at the hands of Proteus up to the imagination. Susan is without a doubt a capable character, her strength highlighted at the end of the film. In a commentary on male intelligence as a force for detriment and destruction, Susan’s ability to ensure the future of mankind by passing on positive human traits worth safeguarding positions her as the positive force in an otherwise bleak film. “Our child will learn from you what it is to be human,” Proteus observes of her.

Visually speaking, even today Demon Seed appears impressively ahead of its time. A particularly spectacular scene sees Proteus show Susan what its “eyes” – sensitive to the entirety of the electromagnetic spectrum – can see. A patterned light show fantasia steals the screen, a hypnotic vortex of psychedelic colours and geometric shapes swirl into oblivion, bombarding us with overwhelming sensory input. A later manifestation of Proteus as a large, unravelled tetrahedron-like object that takes over the basement in a crushing, spinning frenzy could almost be passed off as CGI.

It’s testament to the excellent production design and overall art direction achieved by Edward Carfagno and special effects supervisor Glen Robinson. While it isn’t exactly remembered as a classic example of ’70s science fiction, Demon Seed touches on some interesting themes, and if nothing else, will succeed in weirding you the hell out.

Published 5 Nov 2016

By Ella Donald

The new season of the dark social satire features a refreshingly tragedy-free queer relationship.

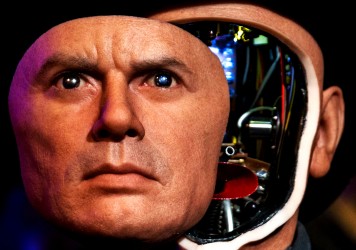

The Yul Brynner-starring original from 1973 expertly fuses futuristic science fiction and classic western tropes.

After 30 years David Cronenberg’s tour de force of disgust is as powerful and penetrating as ever.