Since the release of Franklin J Schaffner’s original Planet of the Apes in 1968, itself an adaptation of Pierre Boulle’s 1963 novel, there have been four sequels, an unsuccessful reboot helmed by Tim Burton, and another much more successful reboot that has spawned two sequels. This is in addition to multiple spin-offs across other media, including comics, video games and television series (both live action and animated), and of course a hilarious Simpsons parody featuring a bedraggled Troy McClure singing “I hate every chimp I see / From chimpan-A to chimpan-Z.”

Amid all this clutter, memory of the original film has become diluted – everyone recognises the image of the Statue of Liberty denoting the twist ending, as well as Heston’s classic “take your stinking paws off me” line, but details of the film as a whole are hazy. Revisiting the film now and looking beyond its iconic moments and images, what emerges is an unnerving, exciting sci-fi, with a sharp satirical edge that astutely exposes and explores the anxieties of the time.

Released in 1968, Planet of the Apes was part of the wave of fresh, experimentally inclined films that came to be known as New Hollywood. Various hallmarks of the era can be found in Schaffner’s film. Jerry Goldsmith’s soundtrack, for instance, rejects conventionality in favour of creating a disquieting tone through a percussion-orientated score full of dissonant noises and irregular rhythms.

There’s plenty of loose, innovative camerawork, including a series of disorienting point of view shots at the beginning as the spaceship boarded by Charlton Heston and his crew crash lands on a planet they do not recognise. And the majority of the film is shot on location in Arizona rather than a studio, its dusty, untouched landscapes perfect for evoking the sense of alien remoteness of the planet the characters find themselves stranded on.

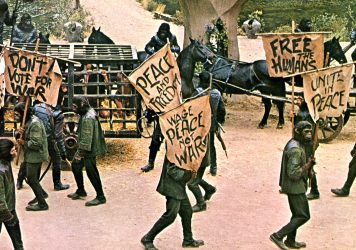

The film is also identifiable as product of its era in the way it relates to to the wider social context of counterculturalism. The film’s apocalyptic aesthetic, consolidated by the infamous revelation that this ‘unknown’ planet is in fact Earth post-nuclear war, in an explicit reflection of the fear of the bomb by a society living through an unprecedentedly dangerous arms race. It has also often been remarked upon how the topsy-turvy society Heston discovers on this planet, where a species of sophisticated, talking apes rule while mute, savage humans, functions as a subversive allegory for race relations, and therefore reflects the tensions in America at the time regarding the ongoing fight for Civil Rights.

But given the social upheaval of the late ’60s, it’s safe to say that the allegory can be broadened to reflect the social landscape in general, where the hitherto underprivileged groups of the younger generation helped reshape the traditional dynamics in society. To the older generations used to the conservatism of the 1950s, it must have felt as though society was not being run by a whole new, strange species of hippies, feminists and rock stars.

In this sense, Planet of the Apes is an expression of the fear felt by the established privileged order of this new generation and their eagerness to uproot everything. The casting of Charlton Heston is particularly noteworthy – having built a star persona around being a traditionally macho white, alpha male in epics such as Ben Hur and The Ten Commandments, he represented a throwback to the kind of hero of yore, who audiences believed could bring order back to this world gone wrong.

Similarly, despite the New Hollywood look and sound, the plot and storytelling generally subscribe to the old-fashioned studio model of an adventure yarn, with plenty of chases, fights, and even a romance with damsel in distress in the form of Linda Harrison’s Nova.

None of this is to say that Planet of the Apes was a work of some kind of reactionary conservatism – quite the opposite. Again, everything hinges on the ending, which is still jaw-dropping despite its familiarity, thanks largely to the brilliant decision to accompany the reveal with a stunned silence on the soundtrack. It invites us to question everything we’ve just seen.

Although the apes had been portrayed as reasonable beings, they were still clearly the antagonists to Heston and the humans – but with the final reveal that the humans had in fact been the architects of their own downfall, suddenly man’s status as the film’s de facto heroes is brought into disrepute, and the inherent worth of what they and Heston represent is questioned. Maybe the basis for Heston’s heroism isn’t quite as infallible as we’d assumed – maybe those that fear a planet run by apes should be more afraid of their own hubris?

Published 9 Jul 2017

There are pertinent lessons to be learned from the original simian-based film series.

This latest instalment in the Apes franchise, about the preservation of humanity, lacks any genuine human characters.

By Matt Thrift

We take an exhaustive look back at the ups and downs of this iconic movie simian.