The poetry and horror of globalisation and manual labour are beautifully evoked in this haunting doc-fiction hybrid.

This is a film which lambasts Chinese cultural imperialism in the harshest terms possible. It accuses a giant excavation project for fossil fuels of creating a literal hellscape on Earth. At one point a camera glides silently along an underground mineshaft before a sudden, terrifying explosion shakes it and the walls around it. After a moment of confusion, it becomes clear that a dynamite charge from the surface is the cause of the rumble, but it could just as well have been the Devil stamping his clawed feet.

Director Zhao Liang heads to rural Mongolia where energy companies insouciantly lay waste to rolling meadow lands. They claim to cheerfully provide jobs for locals with their ecologically ruinous open caste coal mines. Yet unskilled villagers scavenge for nuggets of coke with little more than decorative rags to prevent the dust particles from entering into their bodies and causing chronic emphysema. They head back to their hovels to live out a drab existence, with much of their down-time dedicated to washing off the black grime that cakes their bodies. They’re sustained on a thin broth with limp greens floating on the surface. They have nothing to talk about and no form of entertainment. They sit and contemplate. And then they’re back to work.

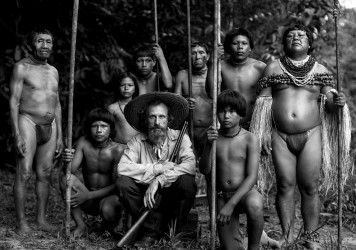

Zhao’s miraculous film is extremely simple in its political aims. It frames capitalist enterprise as uncaring and also clueless as to the desires of its rank and file collaborators. Though the camera often comes extremely close to its human subjects, a psychological distance is always maintained. Communication is a no-no. Zhao doesn’t want to hear gripes, excuses or explanations. That these things he films are happening means that someone, somewhere has flashed the green light. He just wants to watch as the untainted truth unfolds in front of him. He toys with the form, including the occasional fictional insert of a naked wanderer observing the desolation from afar. Sometimes, the manner in which he films a subject transforms it into something otherworldly. At a steel mill, a river of molten metal fills the screen with an intense blotch of glowing orange-red, emphasising the film’s connection to some kind of fiery underworld.

As the film progresses, its scope expands. Zhao shifts his focus from the workers themselves to the world in which they are supposed to exist. The utopian vision of a workers’ paradise is angrily mocked, as an entire metropolis erected on the Mongolian plains lays completely depopulated. Colourful multi-story apartment blocks defile the skyline as workers remain content with their own meagre living arrangements. These ghost towns represent the fight back, the refusal of workers to become entirely immersed within a corporate system.

With this modicum of independence, they are able to exist as more than just drone-like labourers. Though the film is specifically about a single instance in a single place, it speaks passionately and evocatively about the dehumanising effects of industry the world over. It exists to take everything away from us, to own both our time and our bodies. Whether we’re able to fight against it never addressed, but if there is a Devil, then surely there has to be a God.

Published 18 Aug 2016

Chinese documentarian Zhao Liang is little known, but his films are highly acclaimed.

A poetic and disruptive look at modern manual labour.

Rich, deep and eventually very moving.

By Violet Lucca

Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s elegant martial arts tale is one the most beautiful films you’ll see all year.

Ciro Guerra’s film is a stark reminder of the destructive nature of European colonialism.

Mr March of the Penguins returns with an affecting, unhysterical film about the ensuing climate disaster ahead.