Bring Down the Walls suggests that the dance floor can provide liberation from oppressive judicial policies.

In 1980s America, mass incarceration was gaining momentum. Due to the introduction of New York City’s Rockefeller Drug Laws – which could imprison someone for a minimum of 15 years for selling two ounces of cannabis – and the monetisation of prison labour, disadvantaged neighbourhoods found themselves pounced upon by cops ready to wield their new powers and sling more individuals behind bars. Consequently, the “land of the free” is now the world’s largest jailer with two million people behind bars.

As communities found themselves ripped apart by heavy sentencing, the increase in bodies locked up behind concrete walls unusually coincided with the liberation of bodies across dance floors and the rise of house music. While one portion of this oppressed community was severed from society another was responding by building a space of inclusivity, freedom and transformation. And the enduring connection between the black, latinx and queer communities that birthed house music and the battle to abolish the prison industrial complex is highlighted in Turner Prize-nominated artist Phil Collins’ documentary Bring Down the Walls.

Collins initially noticed the link during his time producing music with inmates at Sing Sing Correctional Facility in New York, where sessions regularly returned to the canon of house classics. After his prison permissions were revoked, Collins decided to carry his workshop participants’ passion for house music back over the wall into the community and in 2018 established Bring Down the Walls, a communal space that embraced creativity and campaigning.

During daylight, the project in Manhattan’s Court District was a school of workshops, talks and advisory services, outlining how to instigate change in the inflexible prison system. But once the sun set, the venue transformed into a nightclub, blasting out house favourites with vocals by former incarcerated individuals and production by contemporary, electronic musicians.

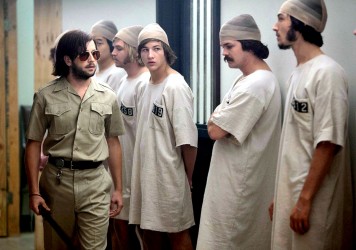

Rather than focusing on Collins and his backstory, the documentary blends shots from Bring Down the Walls with street footage, material from Sing Sing Correctional Facility and archive photography. The result is a hopeful montage of provocative thought, heart-breaking anecdotes and graceful dance moves.

Talking heads with important titles are eschewed in favour of former inmates, who are afforded as much space to speak as the professionals offering big-picture perspective on the justice system. Conversations captured at Sing Sing’s music class blend with presentations at the community project and discussions about sentencing and surveillance bridge the barbed wire divide.

The quiet stillness of shots from the prison contrast directly with the activists at Bring Down the Walls who are infused with life, swaying under the pink light of the dance floor. Interspersed between informative lectures on the history of house or the legality of discriminating against ex-offenders are liberating musical performances from previous inmates. A 70-year-old man who has “spent more time in prison than at home” belts out “You’re gonna miss me when I’m gone” to a packed dance floor of cheers and elevated palms.

The joy and energy that emanates from the gyrating limbs and relaxed smiles removes the societal divides between those that have and have not offended, opening up the possibility that perhaps this juggernaut of a prison system could be dismantled after all.

Bring Down the Walls is part of Sheffield Doc/Fest’s official programme and is available to watch on Doc/Fest Selects.

Published 16 Jun 2020

A robust dramatic rendering of the 1971 psychological experiment conducted in a University basement.

By Thomas Hobbs

Screenwriter Tyger Williams reflects on the legacy of the Hughes Brothers’ controversial crime saga, which turns 25 this year.

By Aimee Knight

This essential, moving documentary challenges the idea of prison as a breeding ground for machismo and violence.