Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop has little in the way of plot; what story it does have seems to trade on the popularity of 1969’s Easy Rider. Only one of its four leads was a professional actor at the time of filming, the rest being two musicians and a teenage model. The action is understated to the point of abstraction. By all rights it should feel like a dated, derivative folly. Yet the film has endured for 50 years as a cult classic and a left-field critical darling.

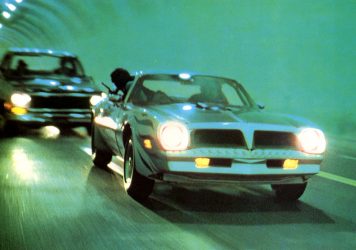

Rudy Wurlitzer and Will Corry’s script concerns a cross-country car race, but demonstrates no interest in petrol-head chases or stunts, steadfastly refusing to yield to audience expectations. Instead, the loose narrative serves as the framework for an existential examination of the American Dream, masculinity, and the curdling hippy ideals of its road movie contemporaries.

The style of Two-Lane Blacktop is restrained and distant, unobtrusively observing its characters go about their business, allowing the protagonists to emerge organically without any explanation of their motivations. Tellingly, none of the leads are identified traditionally – instead, their names derive either from what they are or what they drive.

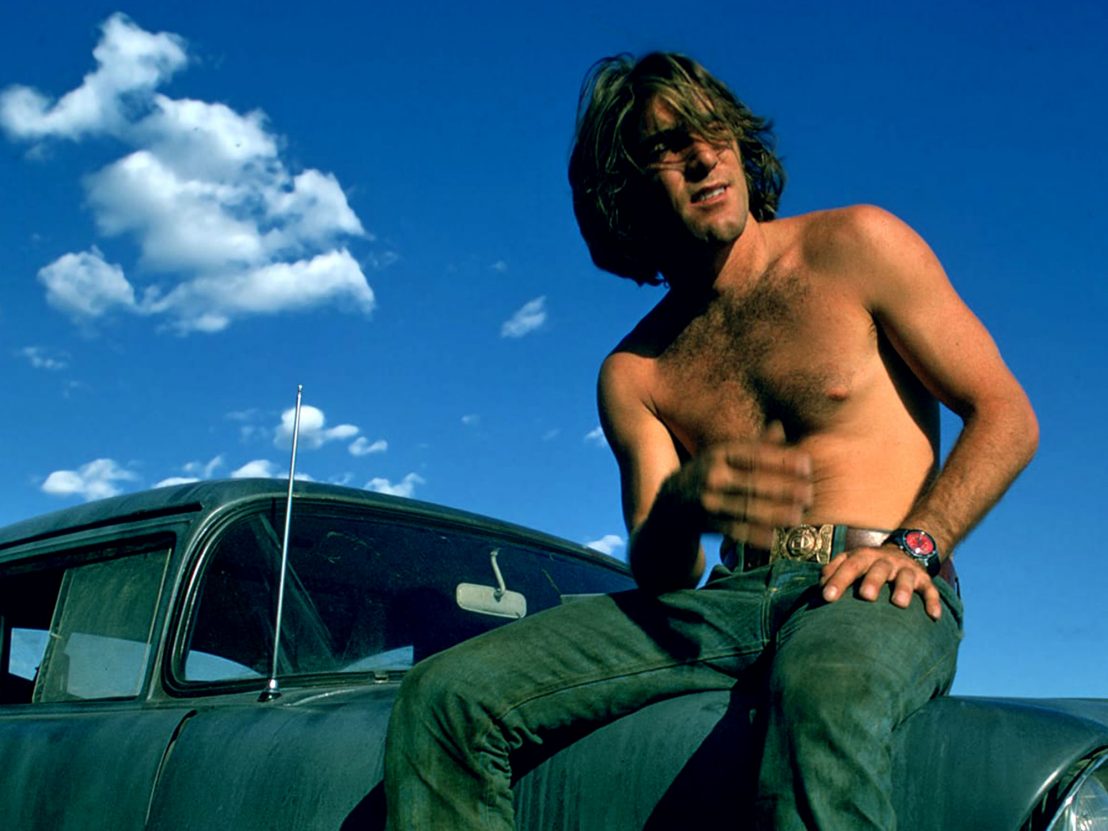

Singer-songwriter James Taylor plays The Driver, a withdrawn, taciturn racer. He traverses the landscape aimlessly with The Mechanic, played by Beach Boy Dennis Wilson. We follow the duo as they race against various inexperienced locals; they seem to live for nothing but their car, but show little joy at their victories. While it’s fair to say that neither musician is a particularly emotive screen presence, their low-key performances perfectly match the vacant, isolated world of the film.

They encounter teenage hitchhiker The Girl, played by Laurie Bird, and she begins to travel with them. While her moniker suggests she will simply be a token love interest (and her presence does create a certain jealous tension between the male characters), the film adopts a more ambiguous approach, with Bird’s composed turn lending a haunting quality to what could otherwise have been a clichéd and thankless role.

“Though Two-Lane Blacktop’s conclusions are less obviously violent than those of Easy Rider, they easily surpass that picture’s force with a biting sense of sadness and desolation.”

The fourth and final protagonist is Warren Oates’ GTO, who challenges The Driver to an epic race along the titular roads to Washington DC. As if to make up for the other monosyllabic leads, GTO is a braggart and a fantasist with an irresistible urge to talk, no matter how hollow his stories are. Oates was one of the finest character actors of his generation, and this may just be his greatest performance. He crafts an utterly compelling portrait of a hopelessly lost and lonely man, a would-be adventurer who simply cannot outrun his own emptiness.

Their race soon reveals a run-down rural America, captured in washed-out tones by cinematographer Jack Deerson. The bleak roads, truck stops and bars encapsulate a depressed blue-collar world, left behind by the cultural revolutions of the 1960s. Nobody appears to be fulfilled, or to really belong there – not even the inhabitants themselves, frustrated and caught out of time.

The characters should be living a key part of the American Dream, free and looking for adventure on the open highway. Yet all they can find is an endless nothingness. They are so alienated from their environment that they never get anywhere near their symbolic goal of the capital. The pink slips offered as the prize (awarding ownership of the vehicles to the winner) are never even mailed, and the race simply wears itself out.

Despite their supposed freedom, the men have simply swapped one conventional conservative world for another. Their empire of cars is just as hidebound, with codified routines, and new parts forever required to keep up with the Joneses. They even squabble over winning a kind of nuclear family for themselves, fighting over The Girl more out of a sense of consumerist possessiveness than genuine passion. They have no real idea of what to do with her as she drifts from car to car, simply desiring ownership of her for its own sake. She eventually leaves them all behind with a withering verdict: “No good.”

Two-Lane Blacktop opens with the monotonous roar of engines over the Universal logo, subtly suggesting that its lonely vision may not just be applicable to the US. Leaving its characters unmoored and going in circles, the film stock literally burns itself out at the end. Though its conclusions are less obviously violent than those of Easy Rider, they easily surpass that picture’s force with a biting sense of sadness and desolation. In many ways, the film’s examination of a world without cohesion rings just as true today as it did in 1971.

Published 7 Jul 2021

By Taryn McCabe

Fifty years ago, The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind kicked off the ultimate counter-cultural genre.

How Wim Wenders’ 1970s Road Movie Trilogy captured the romantic lure of American culture.

Walter Hill’s cult film is full of intense car chases and silent antiheroes.