Damien Chazelle earned himself a handsome reputation with his striking breakthrough feature, Whiplash, which sternly implies that tough love is imperative to achieving artistic goals. The mischievous suggestion floated throughout the film is that JK Simmons’ ferocious taskmaster, Fletcher, may have dubious methods, but it’s precisely this which pushes aspiring drummer Andrew (Miles Teller) to greatness.

While Chazelle’s new film, La La Land, shares a similar jazz background, this time the writer/director looks to be playing a far happier tune. Whiplash was almost comically intense when it came to depicting Andrew’s ambition, and just about self-aware enough to acknowledge it. By contrast, La La Land has been promoted as a feel-good musical revival about the joys of falling in love and following your dreams. The reality is a little different.

Both films are structured around the twin pursuits of art and romance, and in Whiplash it’s clear which one Andrew values more. His music is not just a passion but an obsession, leading to late nights rehearsing alone and bleeding hands, battered by infinite beats. It’s fair to say love is not on his mind. Nevertheless, ripe with awkwardness he acquires a girlfriend, Nicole (Supergirl’s Melissa Benoist); though it’s clear from the word go that she’s not his priority. Even on their first date he spends half his time geeking out over the cafe’s jazzy music and passive-aggressively questioning her lack of ambition compared to him.

The scene where Andrew breaks up with Nicole is the most telling explanation of his personal philosophy. Andrew explains with an almost pathologically unemotional calmness exactly how their relationship is going to pan out. He’s going to want to practise drumming because he wants to be one of the greats, and she’ll want to spend time with him, and those two things just aren’t compatible in his mind. There are two implications: he loves drumming more than her, and romantic love can only ever hinder artistic success.

If the carrot doesn’t work, the stick must be the answer. Andrew sees no benefit in having a loving partner alongside his musical career; instead the driving whip provided by Fletcher’s abusive teaching carves out his path to glory. That bleak argument seems to be reinforced by the film’s climax, where Andrew delivers a bravura solo and finally trumps Fletcher’s attempts to humiliate him, before the two unite to deliver one superb last song. Their abusive relationship may produce some incredible music, but it’s hard to argue that Chazelle fully endorses this message.

Throughout the film he pushes Andrew’s sadism to extreme lengths, most notably in the moment where he crawls out from the wreckage of a car crash, runs to a band performance, and still tries to play. That scene can only be read as a condemnation of both Fletcher’s methods and Andrew’s insane commitment to art over more normal things like having a girlfriend and his own health.

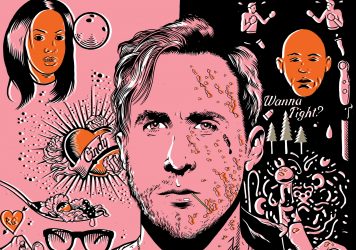

In La La Land, Chazelle explores many of the same questions – namely whether artistic success and romantic love are ever compatible. Its protagonists, jazz pianist Seb (Ryan Gosling) and actress Mia (Emma Stone), are pursuing the same kind of artistic lifestyle as Andrew, but with less naivety. As befits people 10 years further down the line, they’re all too aware that reality must and perhaps should intrude, whether in the form of paying rent or going on a date.

What they manage where Andrew fails – and what also suggests a more mature viewpoint from Chazelle – is pursuing a creative life and a romantic relationship at the same time. For a period, their love provides a salve for the rejection in their fledgling careers. More cynically, in an echo of Whiplash’s main theme, it’s implied that Mia’s eventual success is down to how Seb pushed her, most notably in the breakthrough audition she would have otherwise bailed on.

Ultimately, art and love come into conflict again, when Seb chooses the jazz band whose populist style he despises over supporting Mia’s more genuine passion for her one-woman show. This decision suggests that both of them were more in love with their partner’s mutual passion than each other; all they really needed was someone to believe in them. The couple recognise that their art will always come first and separate, but their love affair with showbiz continues.

Seb opens the jazz club he’d always dreamed of, but without Mia at his side. She’s found love and success elsewhere, now married with a daughter and a bright movie career. Her happy ending suggests that artistic glory and love aren’t as incompatible as it first seemed in Chazelle’s work, but it’s clear which one infatuates him more. Seb and Mia’s romance may be shot with passion and imbued with chemistry by Stone and Gosling, but it’s the magic of show business that both they and Chazelle are really in love with.

Every song is lit with a spotlight, a taste of the stardom both leads hunger for; the very form of a musical allows their deepest desires to be vocalised in the form of song and dance; and even in those songs, it’s Hollywood and showbiz that are being lusted after, not the other person – for example City of Stars’ “City of stars/Are you shining just for me?/I felt it from the first embrace I shared with you”.

Most tellingly, Chazelle favours Seb and Mia’s passion for performing over their artistic ability, allowing endearing vocal stumbles into the songs and hinging Mia’s big audition on an improvised story rather than an example of honed craft. She succeeds not through rigorous training like Whiplash’s Andrew, or even Seb, but through how she turns the emotions of her life into art. In that way, her romance with Seb can be seen as simply fuel for her fire, one more experience that she channels in her acting.

Arguably that passion for an abstract artform over real people leaves Chazelle’s work feeling a little cold. It’s a claim that could be levelled at the mutually destructive pair at the heart of Whiplash, but not La La Land. A love for jazz, or acting, or cinema is one which we can all recognise. Even if you can’t identify with pursuing an acting career, we all have films that we cherish and know the real emotional power they hold. It’s arguably even stronger because it affects everyone who comes into contact with that piece of art, not just one person. It’s the same reason we mourn dead celebrities as if we really knew them, because in a way, through their art, we did.

It’s this strange power that Chazelle harnesses in La La Land, and it’s the real reason why the film is so great. Not only has he created a breathtaking piece of cinema, he reminds us why we love movies in the first place.

Published 14 Jan 2017

Shake, rattle and brawl. A student drummer faces off with his psycho teacher in Damien Chazelle’s pulsating drama.

The Lost River director reflects on his childhood and ponders the myth of the American Dream.

Emma Stone and Ryan Gosling are a match made in old-school movie heaven in this dazzling musical.