Human understanding often relies on binaries: light and dark, right and wrong, good and evil. Martin Luther King Jr’s legacy, while complex, is often framed in contrast to that of Malcom X, who was the subject of one of the great movie biopics, written and directed by Spike Lee and starring Denzel Washington. The image of ‘nonviolent’ King has been constructed in the public consciousness as the antithesis to Malcolm X’s ‘violent’ black nationalism; the two supposed nemeses representing a duality which has appeared time and again in modern cinema.

Malcolm X himself described the pair’s conflict in stark terms: “Black people in this country have been the victim of violence at the hands of the white man for 400 years and following the ignorant negro preachers we have thought that it was godlike to turn the other cheek to the brute that was brutalising us… Martin Luther King is just a 20th century or modern Uncle Tom or a religious Uncle tom who is doing the same thing today to keep negroes defenceless in the face of attack that Uncle Tom did on the plantation to keep those negroes defenceless in the face of the attacks in that day.”

The legacy of this conflict has been passed down through cinema. In Boyz n the Hood, Cuba Gooding Jr’s Tre just wants an end to the cycle of violence, whereas Ice Cube’s Doughboy is committed to violent retaliation. In X-Men, Magneto and Xavier clash while fighting for mutant rights. In The Help, Viola Davis’ spiritual Aibileen adores the white children in her care and turns the other cheek in the face of their abuse, while Octavia Spencer’s feisty Minny seeks retribution against her racist employers. And in Get Out, Daniel Kaluuya’s Chris determinedly gives white people the benefit of the doubt and attempts to win their favour, while Lil Rey Howery’s Rod immediately distrusts and warns against them.

The ideological differences between Malcolm X and Martin Luther King were most recently mirrored in Black Panther. Michael B Jordan’s Killmonger hails from Oakland – the birth place of the Black Panthers – and his father is murdered, just as Malcolm X’s was. He passionately believes in righting the systemic wrongs waged against black people since his ancestors were bound in chains, packed onto ships and sold into generations of suffering and bondage. He is not willing to look to the future until the wrongs of the past are righted. Chadwick Boseman’s spiritual T’Challa, by contrast, though not practicing non- violence by any stretch of the imagination, does not prioritise exacting justice over past ills. He chooses to save Martin Freeman’s Agent Ross rather than pursue Andy Serkis’ Ulysses Klaue, a racist with blood on his hands.

However, King was far from the simple caricature that history and the media has reduced him to. In fact, as evidenced in Raoul Peck’s superlative 2016 documentary I Am Not Your Negro, based on James Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript of the same name, King’s reality was far more complex and his position more radical and fluid than is widely assumed. As Baldwin puts it, “As concerns Malcolm and Martin, I watched two men, coming from unimaginably different backgrounds, whose positions, originally, were poles apart, driven closer and closer together.”

Baldwin’s words are narrated by an almost unrecognisably sombre Samuel L Jackson, who captures the world weary gravitas as well as the warmth he feels towards his deceased friends. “By the time each died, their positions had become virtually the same position. It can be said, indeed, that Martin picked up Malcolm’s burden, articulated the vision which Malcolm had begun to see, and for which he paid with his life. And that Malcolm was one of the people Martin saw on the mountaintop.”

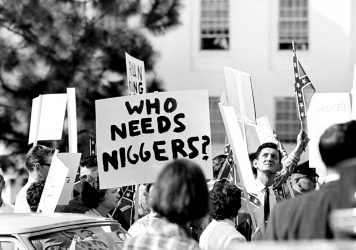

In one scene King is met by contemptuous young white thugs holding banners daubed with racial slurs and swastikas as he marches peacefully with some of his supporters. Sadly, without King for context, this footage could easily be mistaken as contemporary. He is shown to be stoic and solemn in the face of this abuse and even when purporting non-violence, a position he would eventually edge away from, the radical side of his spirit and the bravery of non-violence.

King appears in interview responding to Malcolm X’s criticisms and, with his distinctive and affecting cadence clarifies his philosophy, “We are not engaging in a struggle that means we sit down and do nothing. There’s a great deal of difference between nonresistance to evil and non-violent resistance to evil…” He pauses before laying out the grim reality of what he is asking of his followers. “I think that we can be sure that the vast majority of negroes who engage in the demonstrations that understand the non-violent philosophy will be able to face dogs and all of the other brutal methods that they use because they understand that one of the first principles of non-violence is a willingness to be the recipient of violence while never inflicting violence on another.”

People often misremember King. They think of the safe and gentle soul, forgetting that he openly called for the redistribution of wealth, justified rioting, worked alongside violent organisations like the Deacons for Defense and travelled with armed bodyguards. He was much more aggressive than the Dream time has condensed his legacy down to. By 1967 King’s stance had shifted from strict non-violence to understanding violence as an inevitable means to an end for the Civil Rights movement. Privately, he feared leading black people to a promised land that did not exist.

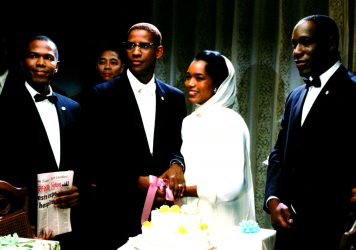

It was with this in mind that director Ava DuVernay chose to cover a three month period in King’s life – December 1964 to March 1965 – in her 2014 biopic Selma, rather than a cradle to grave biopic. As DuVernay sees it, this was, “A time when King was truly hitting on all cylinders, strategically, as an orator, as an organiser, whilst also some of the lowest moments he had personally.” The film was released 50 years after the events it depicted, and marked the first time King was the central focus of a major Hollywood production. This oversight was not simply down to studios’ unwillingness to invest in black stories but also the legal complexities of covering intellectual property contained within King’s life.

Selma showcases King’s gift for uniting people with different ideas, from different organisations, in support of a single cause. The film does not shy away from describing the violence that was inflicted upon those who followed King, or indeed the internal conflict that he himself felt. We see him lying exhausted on a couch surrounded by his impassioned inner circle who are unable to decide where their demands should even begin. We see his shortcomings as a husband, his discomfort with his Nobel prize, the dissent amongst his own ranks and; in Oyelowo’s portrayal, a man whose burden weighs heavy on his every waking moment. This makes the film’s triumph all the more earned – as it was in King’s life, unity was born from conflict, strength from uncertainty and victory from certain defeat.

Published 4 Apr 2018

By Nadia Latif

Spike Lee’s epic biopic of the black civil rights leader offers only glimpses of the great woman behind the man.

Our Obama Era Cinema series continues with Caspar Salmon reflecting on the vitriolic online backlash to recent progress in Hollywood casting.

Raoul Peck’s use of ‘The Blacker the Berry’ in his civil rights documentary I Am Not Your Negro is truly inspired.