It’s unlikely that any other type of dedicated retail outlet rose, prospered, faltered and vanished as quickly and decisively as the video rental store. Once ubiquitous throughout the UK and North America, the act of renting a physical format from a chain like Blockbuster (which had almost 9,000 shops globally at its peak in 2004) will now be a fleeting, peripheral memory for just about everyone under the age of 20.

Jon Spira spent many years of his life in thrall to the world of rental video – as a customer, as an employee of both Blockbuster and several independent shops, and ultimately as an independent video shop owner. Now an acclaimed film director (Anyone Can Play Guitar, Elstree 1976 and the upcoming Elstree 1979), Spira recently published ‘Videosyncratic’, a memoir of his youth and early adult years spent working in video rental. Here he recounts the experiences that informed this wistful, ruminative and hilarious book.

“I had always wanted to own a video shop. I had gone to video shops and worked in the video trade for so long that they were a big part of my life, and I held a deep-seated, arrogant notion that having worked in them for so long, I knew how to do a great one. When the opportunity to have my own shop presented itself in Oxford in 2002, it was actually a bit late – I assumed [the industry] had about eight years left. There are certain kinds of jobs you do because you love it, and because you want that lifestyle, not because you ever expect you’re going to make any money out of it. That’s really what Videosyncratic was about: we never really figured out how to monetise it effectively; we paid our rent, we paid our bills and we had a really good time.

“Clerks is probably the film that had the biggest influence on me. It’s an access point for independent film, and it was the first independent film that didn’t just appeal to a kind of elitist audience. I really love that about it. I was a big Kevin Smith fan, and I idolised his first three movies, Clerks, Mall Rats and Chasing Amy. I suppose that in turn it might have influenced the shop. That said, no one in our shop was openly hostile, though we did have a Clerks poster on the back wall facing the customers which said ‘Just because they serve you doesn’t mean they like you’. No one ever commented on it.

“I would argue that Blockbuster was almost the ultimate retail experience. If you think about it, they were catering to their audience in a pure manner. The main problem with Blockbuster was that there were too many of them and they killed the independents. If there was one Blockbuster in each town and one independent, you wouldn’t have had a problem, because they had two very distinct audiences. But Blockbuster killed off the independents and didn’t replace their business model, and they didn’t service the market they killed off.

“When you walked into a Blockbuster all you saw was new releases. They’d order 80 or 100 or even 150 copies of a new release. I think they actually changed what the audience wanted by placing value in ‘newness’, but I don’t know where that came from. When video shops started they were called video libraries, and it was more about finding something good. Even as a kid who was obsessed with films and watched lots of new stuff, I never figured out why that was a factor in wanting to see a film, the idea that it was the newest in the shop.

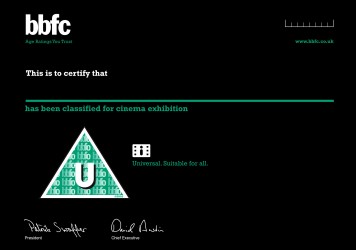

“When I was doing my Kickstarter campaign for the book, I was scouring Facebook because I wanted to advertise the campaign as much as I could, and I found all these incredible VHS groups. I didn’t even realise that VHS collecting was a real thing. Every day these people post about things they’ve found either on eBay or at car boot sales or in charity shops. They’re trying to track down the pre-cert tapes [feature films on VHS released before the BBFC began certifying all UK video releases] and other rarities. Watching what they’re saying and how they’re interacting, you can see their characters emerging.

“I think the next thing we’re going to see in digital culture is the rise of the curator. We’ve got endless choice but no one knows what to watch. The curation on Netflix and the other VOD platforms is terrible. There’s always been a role in our culture for curators. When I was growing up there was a programme on TV called Moviedrome, which kind of felt like having a crazy cousin who would say to you, ‘Hey, you’ve got to watch this!’ It was great to have someone explain why these films were good, it gave them context. I used to buy eight film magazines a month, most of which are gone now, and what’s online has a lot more to do with marketing, especially when you’re looking at Netflix and Amazon. The way they’re pushing stuff – it’s not curation.

“Back in the day – not just in terms of video watching but also cinema going and even TV – you had to be in a certain place at a certain time to watch something, you made a certain commitment to that and you saw it the whole of the way through. With Netflix and other video on demand services, you don’t make that same investment. If you look at people’s Netflix accounts you often see a whole line of ‘continue watching…’ People pause a lot or get distracted. I’m not angry about it; people can do what they want to do, but the fact is, watching a film isn’t so special anymore.”

Videosyncratic is available now.

Published 3 Jun 2017

By Wil Jones

They may seem tame today, but during the home video boom even the trashiest cover artwork could prove intensely effective.

By David Hayles

From Charles Bronson to Chuck Norris, David Hayles offers an indispensable guide to the cult production company.

By Beth Perkin

VOD is forcing classification boards to diversify. But should we be educating young viewers instead of restricting what they watch?