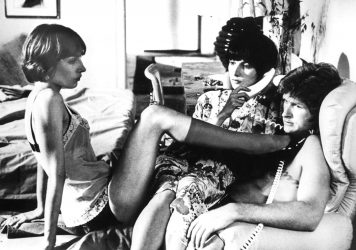

The 1969 film Funeral Parade of Roses, yanked back from the brink of extinction via a new 4K restoration, opens on a context-free nipple. Director Toshio Matsumoto obscures all distinguishing secondary characteristics that may mark this patch of flesh as belonging to a man or a woman, squeezing out any hint of curvature with his extreme close-up. The brightly-lit monochrome lines look more like a landscape than a reclining nude, an abstraction on an otherwise featureless snowbank.

Any viewer recognises the humanity in this anatomy, but the gendered specifics have been stripped away to leave something simultaneously foreign and familiar – until a moment later, when a woman’s head enters the frame to gingerly caress this anonymous torso. Behold Matsumoto’s all-but-lost treasure in miniature: he deconstructs gender, rendering the alien known and the known alien, then uses passion as a vessel to give his confounding semiotic tinkering shape. Funeral Parade of Roses is a film of dense, often conflicting ideas about gender, sexuality, and how identity is forged through the delicate interplay between the two, but the extremes of lust betray it as a work both cerebral and primally felt.

The face that intrudes on that first frame – a gentle, androgynous face, eyes half-lidded and done up with massive false lashes – belongs to Eddie, a transgender street kid who identifies as one of the “gay boys” of 1960s Tokyo. He’s into normal teenager stuff: gettin’ high, gettin’ laid, acting on the unresolved animosities towards his father (or, rather, his daddy) and the messy, charged dynamic with his mother. His reenactment of the Oedipal myth guides whatever semblance of a plot this film can be said to possess, but it mostly acts as scaffolding on which Matsumoto can hang a portrait of Eddie’s specific milieu. With a hallucinatory cocktail of narrative cinema, avant-garde artistry, and verité documentary styles, Matsumoto tore open a portal to a world that, for many, was hidden in plain sight.

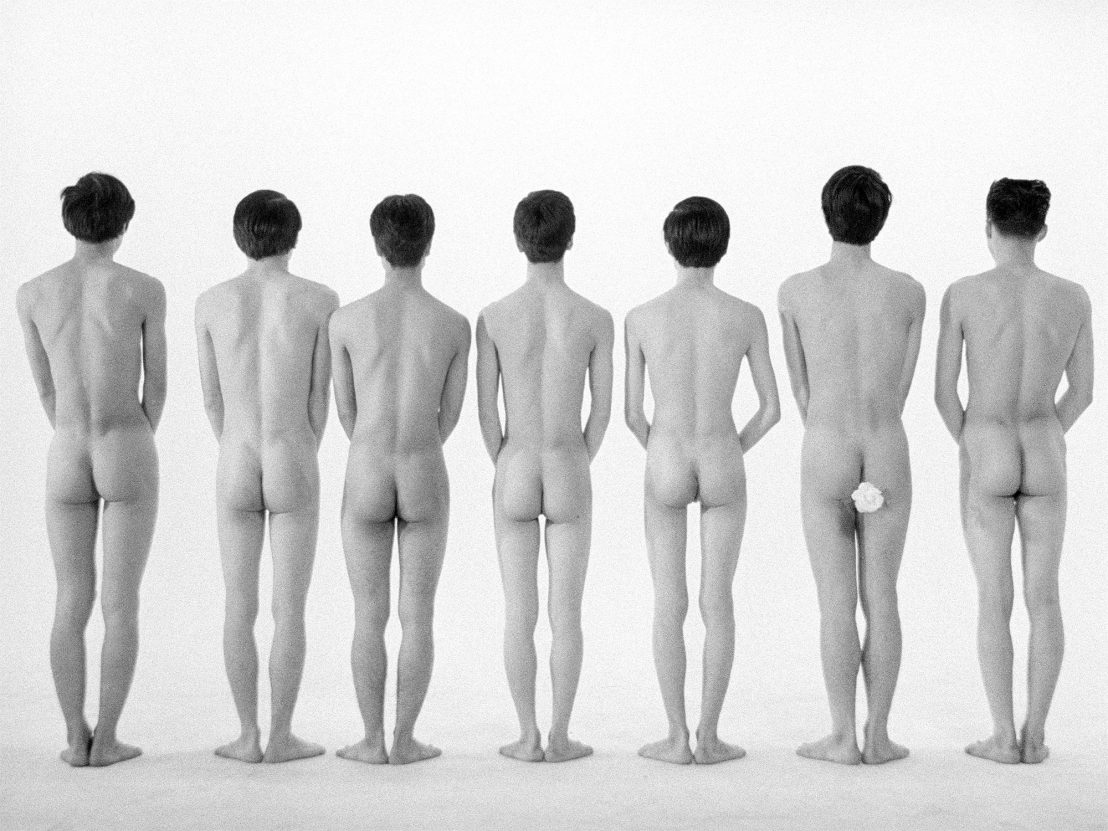

Both Eddie and Peter, the mononymous Japanese comic (so named for his habit of cross-dressing as Mary Martin’s Peter Pan during stage shows) who stepped in to portray him, were children of Tokyo’s hip-n-happenin’ queer underground. Bristling with the pansexual abandon of Weimar Germany with the added hedonistic amplifiers of easy drugs and proto psych-rock, this space permitted the “gay boys” the freedom to live unapologetically, if not as figures of worship. Both the subculture and the film Matsumoto built around it celebrate the body in all of its manifestations, binary and non-binary. If the film objectifies the human form (in one of the more experimental touches, Matsumoto frequently cuts to a non-diegetic image of a butt with a blooming flower sticking out of it), it does so in the same way the devout trembles before a graven image.

Modern audiences may recognise in Funeral Parade of Roses the DNA of another landmark film about the LGBT community, Jennie Livingston’s Paris Is Burning from 1990. Matsumoto punctuates Eddie’s psychosexual spiral with nonfiction talking heads interviews in which he peppers the real-world gay boys with questions about the lifestyle. He affords them a platform to speak about their individual journeys on their own terms, and in vocalising their experiences, they move to dispel misconceptions that still persist today. As one of the gay boys patiently explains that no, liking girls and being a girl is not the same thing, and no, it’s not a choice, you can see him barely suppressing an eye roll. It could be a scene out of any awkward family reunion in 2017.

Like Paris Is Burning, the film supplies edification to an uninitiated audience without sanding off any of the edges that made this particular scene what it was. The documentary segments define terminology and bring those unaware of the particulars through an otherwise insular culture. Matsumoto’s film opens itself up to all viewers, and never in a way that over-broadens the perspective. Consider the fact that one of the film’s most notable disciples was confirmed heterosexual white man Stanley Kubrick, who nicked one sped-up sequence from Funeral Parade of Roses for the hyperactive fuck sesh in A Clockwork Orange.

It’s all too apropos that Matsumoto borrowed from the Greek tradition of drama for his film’s narrative skeleton. The ancient Athenians believed that homosexuality was a mark of refinement, even enlightenment. This dizzying swirl of fiction, metafiction and reality takes a similarly reverent stance towards indulgence, pleasure, and the splendorous body. There would be an orgiastic quality to the film even if it wasn’t packed with literal orgies; it writhes with unruly life, bursting out all over, too frenetic to be ignored and too sincere to be denied.

Funeral Parade of Roses opens 9 June in select US theatres. For more info check out cineliciouspics.com

Published 9 Jun 2017

Gary Oldman delivers a sensational turn in this biopic of the late playwright Joe Orton.

Inspired by Todd Haynes’ Carol, explore our potted history of great films that depict gay lives on screen.

By Leigh Clark

This subversive cult classic imagines a world of empowered women.