A formalist with a forensic eye for detail (and no patience for wading through emotional sludge), David Fincher holds his characters at arm’s length – perhaps all the better to see them in their entirety. Most of these characters are men; Fincher is, after all, a man’s man with a particular predilection for stories about fraternity in crisis (The Game, Zodiac, The Social Network) and the crumbling framework of masculinity in a late-capitalist society (Fight Club, The Social Network and – we think – Gone Girl). However, that is not to say that Fincher’s women are shrinking violets.

There are exceptions; Gwyneth Paltrow’s only notable scene as Tracy, wife of Brad Pitt’s detective in Se7en, is nothing more than a shock in a box, while Chloë Sevigny’s role as Robert Graysmith’s shy, smart wife in Zodiac is so incidental to the plot that she might as well not exist. As for Alien 3’s feminist heroine Ripley – she isn’t exactly Fincher’s creation. Yet, despite these missteps, many of the women in Fincher’s filmography stand out as being equally as interesting, if perhaps not always as well-explored, as their male counterparts. From Jodie Foster’s fierce single mother in Panic Room to the Machiavellian women of the Fincher-produced House of Cards, tough, curious, complex – and as psychologically opaque as any of his misanthropes – women feature in almost all of his features. With his adaption of Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl set to open the New York Film Festival later this month, Little White Lies looks back at some of Fincher’s most interesting, complicated and subversive female creations.

Deborah Kara Unger’s steely, straight-talking waitress Christine facilitates Nicolas Van Orton’s (Michael Douglas) tumble down the rabbit hole created by mysterious organisation CRS. Sexy, resourceful and seemingly fearless, the earthy Christine is worlds away from Douglas’ shivering suited and booted Van Orton – and much more complicated than the average love interest. She maintains the ability to disguise her intentions throughout The Game; whether she’s saving him from a snarling Alsatian as the pair prowl the empty streets of San Francisco’s Chinatown or cajoling him into drug-induced stupor, she retains agency. Yeah, there’s that bit at the end when Van Orton tries to score a date, but even then it’s Christine who asks him if he’s like to join her for coffee.

Given that “I haven’t been fucked like that since grade school” is Marla Singer’s most memorable line in Fight Club, it’s easy to think she’s a bohemian femme fatale, a token designed to titillate in an otherwise all-male cast. However – as Edward Norton’s narrator himself states – “all of this has something to do with a girl called Marla.” Whether you read her as a mirror of the narrator’s splintering psychosis, or the human source of strength he needs to defeat his demons, Helena Bonham Carter’s Marla is as central to the plot as Brad Pitt’s Tyler Durden.

Rooney Mara plays a small but significant role as Mark Zuckerberg’s (Jesse Eisenberg) ex-girlfriend Erica in The Social Network. Mara and Eisenberg’s verbal sparring is thrilling to watch, with Erica delivering Sorkin’s delicious zinger: “Dating you is like dating a Stairmaster.” Zuckerberg’s breakup with Erica is presented as the catalyst for the creation of Facebook, but she transcends her function as a plot device by verbally castrating him, publicly highlighting both his misogyny and his immaturity.

The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo – Lisbeth Salander (Rooney Mara)

Mara is somehow both strong and vulnerable as Lisbeth Salander in The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo. A bisexual hacker with a penchant for punk, Salander exists outside the mainstream, it is Daniel Craig’s bumbling bourgeois journalist Blomkvist who is the foil in Fincher’s depiction of their relationship. While some might argue he fetishises Salander’s graphic rape scene, lingering provocatively on Mara’s gamine body in a shower scene that follows her trauma, Fincher’s formalist approach to the murder mystery at the heart of the story keeps the film from being a revenge tale. Salander is an intensely high-functioning individual who subverts traditional gender roles, pursuing Blomkvist sexually and rescuing him from certain death at the film’s climax.

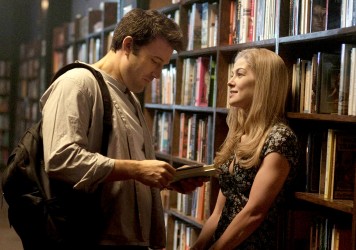

With no previews of Gone Girl available at the time of writing, we can only speculate about how Fincher has chiselled Pike’s regal carriage into the shape of Gillian Flynn’s impossibly icy villainess. Depending on how you read her, Amy can be seen as a man-hating master manipulator; a jealous, highly strung shrew that deceives her husband to punish him for his evolutionary shortcomings, or a fastidious deconstruction of the ‘Cool Girl’ myth. To quote Flynn: “Being the Cool Girl means I am a hot, brilliant, funny woman who adores football, poker, dirty jokes, and burping, who plays video games, drinks cheap beer, loves threesomes and anal sex, and jams hot dogs and hamburgers into her mouth like she’s hosting the world’s biggest culinary gang bang while somehow maintaining a size 2, because Cool Girls are above all hot.”

In Flynn’s novel, Amy writes, “I like strong women” is code for “I hate strong women.” While Fincher’s canon resists the ‘I like strong women’ moniker, his complex, fully-realised female characters suggests otherwise.

Published 12 Sep 2014

David Fincher’s trash procedural for the Twitter age taunts, tickles and, ultimately, terrifies.

The director reveals how he approached adapting Gillian Flynn’s psychological best-seller, ‘Gone Girl’.

The Social Network may not have the impact on the world that Facebook has, but when the story is told this well, it doesn’t have to.