“You gotta show them you ain’t soft.” These words, spoken to Moonlight’s protagonist, Chiron, as a young child, reverberate throughout Barry Jenkins’ film – a quiet masterpiece told as a triptych of vignettes about Chiron growing up poor, gay and black in America. Jenkins’ and screenwriter Tarell Alvin’s experiences of growing up in Miami are crucial in creating a nuanced, palpably real portrayal of the social tensions that thrive in poor black neighbourhoods. Their real-life experiences with people make it onto the screen, turning the picture into a reflection of their childhood in a manner that evokes John Singleton’s seminal 1991 film Boyz n the Hood.

In the opening scene of Moonlight, we’re introduced to a drug dealer named Juan (Mahershala Ali) and his corner boy, with Jenkins drawing on personal experience to set up clichés only to immediately subvert them. Juan, despite his harmful profession, is a kind and surprisingly tolerant man who all but takes Chiron under his wing, nicknaming him ‘Little’, teaching him how to swim, and attempting to instil in him the film’s most important life lesson: “Never let someone else tell you who you supposed to be.”

Both Moonlight and Boyz n the Hood prominently incorporate black music, not just as reference points for the eras they respectively portray, but as thematic hooks too. Most notable is the relationship between both films and hip-hop. Generally, hip-hop is a platform for real stories that might otherwise be ignored, to be told – which is essentially the same thing that John Singleton and Jenkins accomplish with their films. The close relationship to this genre of music makes perfect sense. To this day hip-hop music maintains a complex relationship with homosexuality and images of masculinity, which are only now beginning to be challenged by mainstream acts like Young Thug.

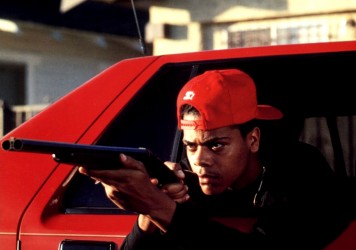

But 20 years ago, when Boyz n the Hood was released, gangsta rap was still very prominent and hardly known for its tolerance. Gangsta rap remains an outlet for anger and frustration, its violent braggadocio evolving from a refusal to be trodden underfoot (see: ‘Straight Outta Compton’, ‘Fuk Tha Police’, pretty much any NWA song). Yet this also extends into a refusal to appear vulnerable, ‘feminine’ or just plain weird. Boyz n the Hood (especially in the casting of Ice Cube as Doughboy) has a closer association with the gritty, disturbing realism of gangsta rap, but also includes the popular black genres that preceded hip-hop, with funk, soul and disco punctuating several significant moments of the film.

Moonlight confronts the issue of masculinity head on through its choice of music. Jenkins uses chopped and screwed music – a remix in which the tempo of a song is slowed down that originated in southern hip-hop. This idea is also applied to Nicholas Brittell’s fantastic score. The recurring theme heard early on in the film has its high notes suppressed, slowed down, going from a regular speed and pitch during Chiron’s childhood, to a much lower pitch and slower speed as the story unfolds.

While the connection between ‘Little’ and Chiron is absolutely clear, the character we meet in the film’s third act is decidedly not someone we recognise straight away. ‘Black’ (Trevante Rhodes) is wholly a product of his environment, opting to mimic acts of masculinity that he’s witnessed throughout his life rather than act on his own impulses. In this segment of the film, ’Black’ plays chop and screw versions of R&B songs, one of which is Jidenna’s ‘Classic Man’, a nod at how Chiron acts as a ‘classic’ (heterosexual) man.

Of course, ‘Black’ is fronting, just how Kevin taught him. In Boyz n the Hood, no one illustrates this kind of posturing – and where it gets you – better than Doughboy. During a scene where a night out turns sour, he says: “This is why fools get shot all the time – trying to show how hard they is.” Both films are make sure to show where this masculine one-upmanship leads. In a particularly painful moment in Moonlight, Kevin attempts to prove his masculinity by beating Chiron, who is targeted for his perceived lack of traditional masculinity by his peers. Here, Jenkins shows the lengths that some young black men have to go to in order to hide any perceived vulnerability.

A lot of characters in Moonlight assume that masculinity means asserting dominance. Kevin is the first example of this, playing up to an image of a heterosexuality that practically comes across as parody. A similarly humorous sequence occurs in Boyz n the Hood, when Tre (Cuba Gooding Jr) tries to impress his dad with a phony story about a sexual conquest. Kevin attempts to keep up appearances are desperate, especially during a scene on a beach with Chiron. Following the near-admission that he cries, he backtracks and responds: “Nah. I wish I did.” It’s almost comical that even in a scene as intimate as this, Kevin feels the need to maintain his hyper-masculine facade.

Moonlight and Boyz n the Hood may be vastly different in style and tone, but there’s enough thematic semblance for these films to be considered companion pieces of sorts. They are personal, unique and honest explorations of the connection between the hostile environments that young African-American men are met with, and how they respond. In response to the question of what ‘makes a man’, both Jenkins and Singleton provide a similar answer: it’s not about adhering to or performing specific gender stereotypes, but rather a feeling of independence, and the right to choose a life for one’s self.

Published 14 Feb 2017

A welcome re-release of John Singleton’s emotionally wrenching ghetto saga heads up the BFI’s Black Star season.

By Josh Lee

By not showing physical intimacy, Barry Jenkins allows sexuality to surface in his film in other ways.

By James Clarke

John Singleton’s South Central LA story delivered a powerful universal message that still rings true today.