The ‘Black Film, British Cinema’ conference, organised by the writer and art historian Kobena Mercer, was first held at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1988. Nearly 30 years on, a new incarnation now run by Dr Clive Nwonka welcomed audiences at Goldsmiths University and the ICA. Over two days in central London, the conference of academics and filmmakers attempted to tackle a multitude of questions around blackness, Britishness, the relationships between film cultures and national identities, and the potential of digital spaces as the new forum for black voices.

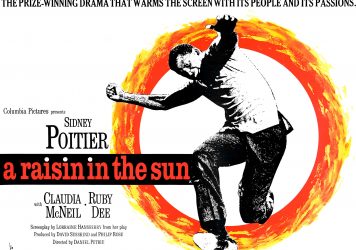

Simply put, what has and hasn’t become of black British cinema? Unlike British Asian cinema, which has seen a number of box office hits including East is East and Bend it Like Beckham, Black British cinema has never truly had its moment in the sun. It is tempting to be overly nostalgic about the might-have-beens from Black British cinema’s past. But when faced with the cultural concussion of another hyper-masculine Noel Clarke film, one cannot help but long for Horace Ové, John Akomfrah and Isaac Julien.

Yes, we have had the first glimmers of success with directors such as Steve McQueen and Amma Asante. Yet the capitulation by both filmmakers to making films where blackness is a social/political “problem” suggests that, in fact, black cinema has not come as far as we might like to think. Is it possible that in this world of neoliberal multiculturalism, another wave of proudly black and truly radical filmmakers could emerge? At a time when the sense of a collective black identity is being fractured and re-fractured, because, as Stuart Hall once put it, “in the age of refugees, asylum seekers and global dispersal, black will no longer do,” do we even really know what a Black British film is any more?

The BFI has been doing sterling work in amassing some very comprehensive statistics about diversity in British film. There has been much talk of the diversity of on-screen talent: the most telling of these statistics is that in the past decade only 13 per cent of all UK films have featured one or more black actors in a leading role, 59 per cent have no black actors in any named role, and that 50 per cent of all the roles played by black actors have been clustered in only 47 films (less than five per cent of the total films produced in that period). However, when you include the wider UK film ecology, we discover that overall BAME film employment has also in fact fallen to less than three per cent. It is undeniable that black people do not make the cut as stories or as staff.

Certainly there is plenty to despair about, but there are also a lot of highly-publicised diversity schemes and initiatives at a number of film institutions and companies. Although, to quote Gaylene Gould, “We don’t need more schemes. We need more jobs.” From the online and real-life vitriol I personally received while taking part in one such diversity film scheme, it seems that some conservative thinkers believe diversity has gone too far, and identity politics has gone mad.

They needn’t worry, because every so often the industry has a spasm of conscience, much like its current one, and talk of diversity bubbles up. A few prizes are given, a few careers are made, there are some relative successes. But there has never been a true step-change that puts black filmmakers firmly in the club, or as Bidisha put it at the conference, “We are never considered as a right and natural and permanent contributor to the history and future of our art form. We are seen as exceptional, as contingent.”

So what of the exceptions? Can McQueen, as the first black person to win the Best Picture Oscar (the ultimate hallmark of mainstream assimilation) really be The Great Black British Hope? There are those that do not consider McQueen a Black British filmmaker because he does not make films about Black British life (there is a rumoured BBC project). I would argue that McQueen moves beyond that somewhat antiquated notion of identity, to what is potentially the real future of black filmmaking – black gaze on white bodies.

His fetishisation of Michael Fassbender’s physical and political body in Hunger and Shame is perhaps his most radical quality – to turn the lens of cinema, which has for so long fetishised black bodies as mammies, sidekicks and fuck fantasies, back on itself, and hold white masculinity to account. I’m aware that the burden of responsibility on McQueen is deeply unfair, but I can’t help but feel let down by 12 Years A Slave as a return to the well-trodden narratives that white filmmakers have been peddling about black people for years.

Though I find the idea of being in a “post-racial” era nonsensical, the idea of a “post-cinema” age intrigues me. People in a variety of locations have access to the technology of film and video production, and to the means through which to distribute it. This is the age of Netflix and YouTube, where filmmakers do not have to compromise their vision via networks and studios in order to reach an audience. So do digital platforms provide a real opportunity for re-democratising films, handing power back to filmmakers, and even becoming creative spaces for communities?

A new wave of incredibly talented black British filmmakers including Cecile Emeke (Strolling), Kibwe Tavares (Robots of Brixton) and Usayd Younis & Cassie Quarless (Generation Revolution) are all making noise online. In a way, digital cinema fulfils a dream of Third Cinema, the dream of a non-commercialised, collaborative, revolutionary and democratic cinema the appeals to the masses. But are we actually just kidding ourselves? There is much evidence of the racism of search engine algorithms – and we know that the internet is designed to show us more of what it knows we already like. So are online audiences really new audiences for black work, or might it in fact be a digital ghetto? Moreover, by moving into new spaces, we do not solve the inequalities of the mainstream.

After two days of listening, talking and soul-searching, I do not know if I can tell you what a Black British film looks like. Maybe it was easier to define 30 years ago – black identity itself was more binary, and now it is prismatic. What I do know, is that for black British cinema to truly move forward, it must do so on dual fronts.

Yes, there must be mainstream commercial success that acknowledges the enormous black audience in our multiplexes who are hungry for more. But there must also be a reinvestment in radical, aesthetic-driven, and proudly black (in any sense of the word) filmmaking. Because isn’t that real freedom? The ability to be experimental, be avant garde, to just make art. It’s been the reserve of white artists for far too long.

Published 8 Jun 2017

Our Obama Era Cinema series continues with Caspar Salmon reflecting on the vitriolic online backlash to recent progress in Hollywood casting.

John Singleton and Barry Jenkins’ films understand what it means to grow up young, black and American.

These beautiful, revealing posters highlight African-American culture’s contribution to cinema.