Young actress Nina is shocked when she returns to her native Brixton after a few years living in east London. Communities she once knew have been forced out, small businesses have closed to make way for “gourmet jerk chicken shops”. Nina decides to make a film about Brixton’s gentrification, while examining her own complicity as an now-trendy returnee. But at a research meeting, an activist is openly hostile towards her self-described “visual art project”. “Them kind of projects, they don’t mean shit. Not to real people,” he says to her obvious dismay.

Is that activist right? Can films, no matter how well-intentioned, really make a difference? This is the crux of A Moving Image, the feature debut from 32-year-old director Shola Amoo. A south Londoner of Nigerian descent, Amoo admits that Nina’s neurosis is really all his. “They are 100 per cent my thoughts on art – and are still my thoughts on art – in the face of social structural upheaval,” he tells LWLies. “Art’s usefulness to confront gentrification, as well as art’s complicity in it, is a big question for me. My aim was to start a conversation, but through facilitating that conversation be a catalyst for some kind of broader change.”

This blurring of fiction and reality doesn’t end with Amoo’s proxy character. The director mixes in footage of real-life protests and interviews with locals into Nina’s fictional story arc. At one point Nina, played by Tanya Fear, solicits video responses from people living in Harlem and other American gentrification hotspots. These were real videos taken from Amoo’s online gentrification database on the film’s website

Amoo bills A Moving Image as a multimedia film and believes that, “Cinema now has got to the point where the engagement isn’t just with the film. It’s part of the broader conversation that takes place in the digital space as well. Outside the film there’s other stuff you can engage with, like my database. You can take it onto social media and have discussions with other people.”

From Harun Farocki to Ken Loach, filmmakers have long struggled to visualise the vast, invisible social structures to make a film that “means shit”. A Moving Image seems very much a millennial take on political filmmaking. Acutely aware of self-reflexive identity projects, and embracing innovative multimedia, it focusses on the personal as the political. “I wanted to look at the individual rather than the council planning and the development projects that happen on the macro level,” says Amoo. “In exploring ourselves and how we deal with structural changes, there was more potential to look at cultural nuances.”

A Moving Image is adept at demonstrating the slippery, nebulous nature of gentrification. But like a horror movie that never reveals its monster, the film doesn’t bring to light the root political and social causes of gentrification. The politicians failing Brixton’s less affluent residents, and the well-off newcomers enjoying black culture minus the black people, seem get off relatively lightly, despite the occasional kale joke.

Even after making this ambitious film, Amoo is honest about his ambivalence of filmmaking as a political force. “I’m still waiting to be shown the true power of cinema,” he says. “I can’t say I’ve completely seen it or understood fully its full capabilities. That’s part of the journey – the push-pull of what does it take for a film to be more than a film? That’s a question I’m still trying to answer.”

A Moving Image screens at Ritzy Picturehouse, Brixton and Hackney Picturehouse on 28 April. The film will receive a wider release the following week.

Published 11 Apr 2017

By Sam Thompson

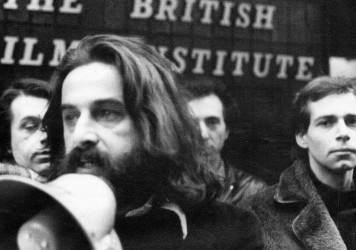

Radical socialist filmmaker Marc Karlin emerged as a key counterculture figure in the 1970s and ’80s.

By Beth Perkin

Collectives like the WFC are providing the tools to enable people around the world to create meaningful connections.

This 1966 TV play on a young woman’s descent into homelessness has lost none of its impact.