The maverick filmmaker of his generation takes on the most popular children’s book of all time with mixed results.

Breaking through in the fabled filmmaking class of ’99, Spike Jonze did everything but dress up in a wolf suit to prove that he was an original Wild Thing. Forged in the fires of gonzo publishing, skate and music videos, Jonze reflected a new American aesthetic that combined reckless bravado and youthful energy with an instinctive feel for the feral power of film.

Being John Malkovich emerged fully formed from the Siamese brain space of Jonze and screenwriter Charlie Kaufman. Electric and elusive, with it Jonze graduated from the MTV gunslinger behind Björk and the Beastie Boys, merging the sensibilities of ‘serious’ moviemaking with style-conscious modernism and intellectual swagger. Three years later, Jonze and Kaufman produced Adaptation., whose narrative pyrotechnics dynamited the final, brittle boundaries of conventional filmmaking. But that was then. Seven years have passed. Seven years in which the class of ’99 – the likes of Wes Anderson, Sofia Coppola, David Fincher and PT Anderson – have evolved in their different ways. But while his contemporaries have suffered their slings and arrows, Jonze has been curiously silent.

It was in that silence that an adaptation of Maurice Sendak’s ‘Where The Wild Things Are’ gestated. The story of Max, a young boy sent to his bedroom with no supper who journeys across the sea to the land of the Wild Things, it was published in 1963, earned a Caldecott Medal and has since taken up residence in any list of the best selling kids books of all time. The book has been circled by a succession of filmmakers tempted not just by its high profile but by the rich possibilities for translation to the screen. Until now, the story’s economy and maturity have defeated them all, but given the childlike qualities evident in Jonze’s elastic cinematic worlds, it seems like the material has finally fallen into the hands of the perfect director.

When following Max’s harum-scarum flight from home, or the wild rumpus in the woods, propelled by Karen O’s exhilarating soundtrack, the film lodges itself in some post-conscious part of the brain and sends out pure bolts of cinematic bliss. Sendak certainly thinks so – giving his blessing to the project for the first time. And why wouldn’t he? Looking back at Jonze’s previous films, there are thematic parallels between the work of the two men. Sendak intended his Wild Things to serve not just as traditional cartoon monsters but as physical manifestations of Max’s emotions.

Published two years after the death of Carl Jung, it’s no coincidence that Where The Wild Things Are brings the realm of the unconscious to life. For Sendak, it was also a form of art therapy – another Jungian conceit – capable of expressing the feelings of trauma and alienation that haunted him in secret for most of his life. Jonze, alongside Charlie Kaufman, has also fixated on visualising the unconscious. Whether getting into the literal head space of a famous actor in Being John Malkovich, or physically dramatising the multi-layered personality of a screenwriter in Adaptation., he’s been able to bring a feather-light pop-cultural prescience to Kaufman’s complex philosophical psychoses.

So here we are, five years later, breath-bated and feverish with anticipation. Because this isn’t the usual Spike Jonze joint. Whether casually reinventing the pop promo, making slyly subversive ads or quickening Hollywood’s pulse, Jonze has always made it look easy. He stole out of leftfield, spending creative capital rather than studio cash. He made films with tight-knit crews and guerrilla energy. He was quick and sharp and spontaneous. What happens when you bring that filmmaker into the studio system, where the answer to any question is counted in dollars (seventy million of them in this case)? What happens when he’s in charge of production with a crew of over 400 people, where every shot must be painstakingly mapped out over a series of months? What happens when he answers to five producers, four executive producers and three separate film units?

The answer, perhaps inevitably, isn’t straightforward. Because for all that Where The Wild Things Are is redolent of the exuberance, love, fear and loathing of childhood, it is also an unwieldy, conflicted, awkward teenager of a film. It’s a film of occasionally transcendent highs that nevertheless creates icicles of disappointment in the gut. It’s a film that you’ll desperately, desperately want to love. But won’t.

At its best Jonze’s film locates within the dark heart of childhood a nesting place of loneliness and confusion. Max – brilliantly played by Max Records as a combination of boisterous free spiritedness and fearful introspection – is a child on the cusp of change. His single mother (Catherine Keener) has a new boyfriend, while his sister is drifting away from him into adolescence. Left alone, he’s gripped by separation anxiety and a sense of betrayal. At school, he learns that one day the sun will die too, and as this ultimate cosmic abandonment takes shape in Max’s fragile sense of reality, his paranoia morphs into existential dread. In other words, he dons a wolf costume, bites his mum and runs away.

In a transition signified by a shift in light and texture, Max is transferred to the land of the Wild Things – giant creatures caught in a primal cycle of creation and destruction, the embodiment of a nine-year-old’s often-violent worldview. A combination of puppetry, performance and CGI, the Wild Things are a technical marvel. Designed by artist Sonny Gerasimowicz, they were constructed by Jim Henson’s Creature Shop in LA while the voice actors spent two weeks performing a live stage version of the script. Puppet actors then worked the suits on set in Australia before CGI features were overlaid to add an extra layer of expressiveness.

The final effect is an elegant assembly of engineering and art – the Wild Things of Sendak’s drawings finessed by the imagination of Jonze and the hard work of actors and experts. Their very weight and physicality prove crucial to the emotional resonance that makes the story tick. They run and leap and fight and howl with a menacing but paradoxically otherworldly ‘realness’, with a history written into their bodies in snapped toenails, gouged horns and crusted fur.

Jonze and cinematographer Lance Acord shoot them in natural light, reflecting the fact that childhood isn’t the primary-coloured paradise of Disney, but a world of hazy sunlight and hidden shadows. Further naturalising the Wild Things within their surroundings, it’s Max’s troubled and unsatisfactory home life that begins to look like the fantasy world.

There is also, perhaps, in this hermetic kingdom of the imagination a comment on filmmaking itself. Max and the Wild Things build a fort – another physical symbol of their inner feelings – where ‘only the things that you want to happen, happen.’ But as that fort is metaphorically and literally destroyed from within by a petty procession of lies, compromises and disappointments, it’s hard not to see it as an unwitting reflection of the filmmaking process.

Just like the Wild Things themselves, Sendak’s book was looking for a king and in Spike Jonze it found the wildest one of all. But even that ultimately hasn’t proved enough to offset five years of frustrations, studio arguments, technical hitches and disastrous test screenings. Because at the same time that Jonze lifts us out of the comfort zone of traditional kids films, a nagging sense of familiarity keeps us grounded. The film’s tension between domesticity and wildness is never convincingly resolved. Instead, the relationships among the Wild Things are played out as a series of almost sit-comic archetypes in which the ‘Wife’, the ‘Husband’, the ‘Loner’, the ‘Serious One’ and so on trade improbably random snippets of dialogue like a child’s eye parody of a soap opera.

No doubt this is part of Jonze’s commitment both to the spirit and the logic of childhood where life is more easily viewed as a series of non-sequiturs and fleeting thoughts, but the cumulative effect is of narrative threads slowly unravelling. That very sense of slow disintegration is telling, because the film has only two speeds: flat out and dead stop. When following Max’s harum-scarum flight from home, or the wild rumpus in the woods, propelled by Karen O’s exhilarating soundtrack, the film lodges itself in some post-conscious part of the brain and sends out pure bolts of cinematic bliss. These are the scenes in which you can feel Jonze behind the camera channelling his enthusiasm through the screen. But when it’s not doing that, Where The Wild Things Are grinds to a halt and the spotlight is shifted onto a script that can’t bear the scrutiny.

Unmoored from the dynamic abstruseness of Charlie Kaufman, some of Jonze’s choices seem wilfully odd. Additions to the book include a giant dog and talking owls. Why? Well, this is a child’s world – the why is irrelevant. But this is also a piece of cinema with certain stylistic and narrative demands, ones that Jonze is unwilling to meet.

The fact that the film is co-scripted by Dave Eggers adds an extra frisson. His first novel, ‘A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius’, detailed the emotional fall-out from the death of his parents, and the enforced and painful period of growing up that followed. But while Eggers’ fingerprints may be on the film’s more tender scenes in which Max and his mother share a quiet and convincing bond, he isn’t able to balance Jonze’s flights of fancy with the screenwriting rigour that Kaufman understands instinctively.

Gradually, Max will realise that life is a state of change – that all good things come to an end, and sometimes what’s fun isn’t what’s right. Neither Sendak nor Jonze shy away from the uncomfortable truth that childhood is a time of insecurity and cruelty; when we lash out in our confusion at the world and insist – against all the evidence of our ignorance and fecklessness – that it should treat us as its king. It is, to use that maddening, evasive but ultimately accurate phrase from adulthood, ‘complicated’.

And the same is true for Jonze. Where The Wild Things Are is complicated. It moves smoothly from the sublime to the ridiculous, it inhabits the dual worlds of fantasy and reality, and articulates something profoundly simple about both. But what’s fun isn’t always what’s right. Like the trees in the Wild Things’ forest, there’s a hole in the heart of this film – something missing that can’t quite be covered by all the industry and artistry that five long years could muster.

It’s the spark of inspiration, the easy charm and reckless bravado of Jonze’s earlier work. This may be his most ambitious film ever but it’s a hard one to go wild for.

Published 11 Dec 2009

Spike Jonze takes on the most popular children’s book of all time. Minds will be blown.

In between moments of pure joy, the film’s narrative inconsistencies fire tracer bullets of disappointment from the screen.

There is enough that’s good about the film to suggest it may grow rather than diminish over time.

Whimsical futuro-romance effortlessly evolves into ambiguous, unfathomable hard sci-fi in Spike Jonze’s best film to date.

LWLies gets up close and (too?) personal with the cherished Her director.

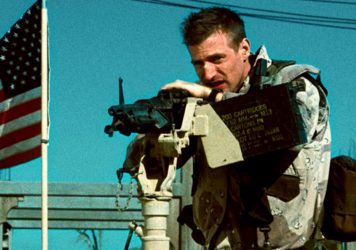

His role as good-ol’-boy Conrad Vig is one of the great examples of directors acting.