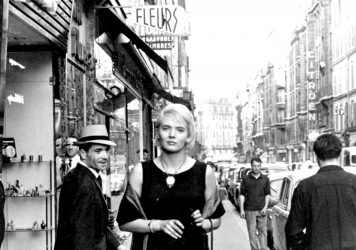

A welcome re-release of Agnés Varda’s best film, chronicling the final days of a French wanderer in search of freedom.

So often in Agnés Varda’s 1985 ghost story, Vagabond, the camera tracks across a landscape before the image fades into nothingness. Then, a flicker of black before a new image bursts forth. This smooth, gliding action gives the camera the feel of a floating apparition observing a moment while in transit, attempting to draw in as much detail as possible but never stopping to stare.

This never feels like a purely cosmetic decision, or a way to imbue this deeply melancholic text with undue dynamism. It does, however, transmit a feeling of evanescence and impermanence, the idea that it’s impossible to really have the time, the inclination or even the emotional agility to understand the wilful desires of others.

Having delivered one of the great lead performances of the decade in Maurice Pialat’s brittle 1983 teen movie, A Nos Amours, Sandrine Bonnaire once more shows herself as a master of playing indefatigable and free-spirited women masking deep wells of fragility and confusion. The tragedy of this film, in which she stars as a transient named Mona (aka Simone) wandering aimlessly around the scrublands, graveyards and community farms of Montpellier, is that we know her fate from the off.

In the opening scene, Varda shows us Mona’s frozen corpse in rigid repose, blanketed in dirt, at the bottom of a drainage ditch which runs down the edge of tatty vineyard. This film, as Varda herself acknowledges in an opening monologue, is an attempt to re-trace Mona’s final days – a poetic soliloquy for an unknown woman.

Mona has a feral quality which means she doesn’t mix well with others. With each new person she meets, a fast friendship is formed as quickly as it burns out to nothing. She could be read as the physical embodiment of freedom – that is, a person who has staunchly chosen to opt our of civilised society and exist through alternative means. It’s never really specified what happened in her past that prompted her to go it alone, but she is militant in her apolitical outlook, never moved or convinced by the pleas of those who want to help her, to bring her back into the capitalist fold. She symbolises the elusive, abstract and erotic nature of freedom, a concept rendered meaningless in her refusal to exist within a defined system.

Varda tries hard to mask her natural affection for the iconoclast Mona, but she can’t help but frame this charming wanderer as a plucky folk heroine. The people she meets deliver monologues to the camera, attempting to define her through their vague memories. She is romanticised to a degree, which makes her plight more tragic. She is raped off camera but she takes various indignities in her stride. Despite its doomy end point, Varda’s film offers a compassionate depiction people who always want to help out a lost soul. The very fact they remember Mona suggests that they are open to forging new bonds, building new relationships and, wherever possible, letting love in.

Vagabond is a film which combines everything that Varda does best: a story ripped from the headlines which she refuses to fully fictionalise; a strong female lead who battles against a patriarchal system and against people who can’t comprehend her anxieties; a love of those liminal spaces between cities, roads, buildings – locations which appear as blank spaces on maps; a belief in building stories through small nuance rather than sweeping gestures. On that last point, you must watch this film (or, indeed, rewatch it) for a moment where Mona scoops the contents of a can of fish into her mouth and wipes the oily remnants across her face – a poetic vision of unselfconscious contentment which defines this beautiful character.

Published 28 Jun 2018

Of her many great movies, this one is often considered to be Agnès Varda’s masterpiece.

Perhaps down to Sandrine Bonnaire’s transcendent performance, yes it probably is.

An exceptionally beautiful film.

By Adam Scovell

A curiosity in the everyday powers Agnès Varda’s masterful second feature.

Ava DuVernay, Josephine Decker and Mia Hansen-Løve feature in the final part of our celebration of women filmmakers.

The French writer/director’s debut feature from 1988 is an elegant, perfectly poised character study.