Wes Anderson returns with an opulent and strangely moving caper movie.

Wes Anderson made a credit card commercial back in 2004 in which he satirised the jodphur-sporting, bull-horn wielding autocrat that forms our romantic conception of what a film director is and how he/she operates. Anderson himself starred in the amusing short and is seen sashaying around a movie set as toadying flunkies fall at his feet so that he may personally anoint their creative proposals.

This motif – the single heroic figure flanked by his loyal charges – has since appeared in The Fantastic Mr Fox, Moonrise Kingdom and now forms the ideological core for his predictably delightful new work, The Grand Budapest Hotel. We may have inferred spurious behavioural similarities between Max Fischer, Royal Tennenbaum or Steve Zissou in the director himself – characters as an extension of the creator’s personality, as the auteurists would have it – yet this latest work appears wholly obsessed with the mechanics and logistics of Anderson’s experience writing and directing movies.

The film is a fleet-footed, ultra ornate mittel-European caper with all retro fittings in place and bursts of cartoonish macabre filling in where the Martini dry humour once was. And here the genteel, syllable-heavy olde world dialogue is written to dovetail with the customarily meticulous production design and Robert Yeoman’s snowglobe framing. The cinematic reference points range from Lubitsch, Murnau, Von Sternberg and famed German silhouette animator, Lotte Reiniger, right through to Kubrick (particularly The Shining), while the film is said to be primarily inspired by the writings of Austrian literary stylist, Stefan Zweig. The delicate wordplay in the script feels, if not purloined from Zweig’s pages, then certainly studiously and fondly recalibrated for the big screen with Anderson’s customary reverence.

Subtle pangs of melancholy – that Anderson staple – permeate every immaculate frame, even as the film’s plot barrels along at a more spritely pace than usual. This melancholy arrives in its opening frames when a young woman hangs a hotel key on a bust/memorial and begins reading from a hardback entitled ‘The Grand Budapest Hotel’.

Once we are two, three layers and two aspect ratios removed from contemporary reality (or Anderson’s slightly less geometrically precise vision of contemporary reality), we are introduced to the world of this baroque mountaintop spa hotel, lorded over by the obscenely devoted and motor-mouthed concierge M Gustave (Ralph Fiennes) and his pencil-mostachio’d lobby boy-cum-protege, Zero (Tony Revolori).

If Gustave – barking orders, maintaining standards, holding the future of the establishment in the palm of his hand – is the Anderson manqué, then the eponymous grand hotel stands in for his idiosyncratic brand of cinema. He doesn’t so much have supporting players in the film as he does an extended family of cherished guests who he invites to stay for a while, relax and soak up the ambience: French it girl Léa Seydoux has a part as a maid which may as well be non-speaking; Owen Wilson plays one of M Gustave’s concierge brethren and gets a line (if not a laugh); even Tilda Swinton makes a flying visit to Wesworld, caked in gristly prosthetics as an ageing dowager who drops dead after her first and only scene, her passing acting as deus ex machina for an elaborate art heist involving the whereabouts of the apocryphal, priceless chef d’oeuvre, ‘Boy With Apple’.

Although the murmurings of European conflict can be heard in the backdrop of all the cross-country capering, Anderson co-opts the period’s social rather than political detail. Accent-wise, Fiennes does a loquacious spin on his English Patient but peppered with bizarre Americanisms (goddamn!) and fruity sign-offs (darling).

The baddies of the piece, brothers Dmitri (Adrien Brody) and Jopling (Willem Dafoe, replete with Max Schreck-style lower-jaw fangs), have a mild germanic lilt, while there is French dialogue from Seydoux and Mathieu Amalric. Saoirse Ronan (as Zero’s pastry-chef fiancé with facial scar) retains a Northern Irish twang. This geographical melting pot helps to maintain a sense of fantastical distance, reminding us constantly that a movie is a whimsical fabrication of reality – and that we are watching a movie.

Anderson often prizes in-the-moment emotion over contrived drama, though with this film you feel that tricks are sometimes being missed. There is a mystery element to the plot – Who’s got the painting? Where’s the second will? How will Gustave break out of jail? – though Anderson always opts for telling you how something is going to happen first, allowing you to watch and soak up the rich aesthetic detail.

A sequence in which the family lawyer, Kovacs (Jeff Goldblum), is being chased around an art gallery by a knife-wielding Jopling, his fate seems pre-destined, a foregone conclusion. It’s not will this happen, it’s how will this happen. The frame is there as much to show as it is to conceal, and one wonders if the film could not have been supercharged by simply allowing a few blank spaces for the audience to fill. But then with Anderson the process is the story and the details are the drama.

Even though from the outset The Grand Budapest Hotel announces itself as a jolly trifle, its cumulative power catches you daydreaming. Anderson has this innate ability to shoot a moment through with intense sadness through a repetition, a realisation or a tonal remove. The finale of the story is largely upbeat, but then we are back dragged back through time, through literary devices, through narrators, interpretations and dreamworlds and back into the snow-swept reality of the girl stood alone, clutching the hotel key. This sadness derives not from the fact that the story has come to an end, but that it was all just a story in the first place.

Published 6 Mar 2014

It’s been barely a year since Moonrise Kingdom, but you can't keep a good Wes-head down.

The haters will no-doubt hate, but this is a sparkling effort with an utterly endearing lead turn from Ralph Fiennes.

An opulent and elaborate cartoon romp that exists under a deep ocean of Andersonian melancholy.

Wes Anderson’s brilliant debut, which turns 20 this month, channels the youthful spirit of Mean Streets.

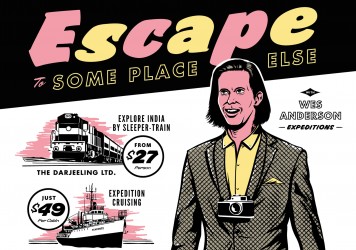

The inimitable writer/director throws open the doors to The Grand Budapest Hotel.

The Whitmans, the Tenenbaums and others lifted my spirits at a time when it seemed nothing could.