Mao! Mao! Mao! Michael Cimino invites horrific ’Nam flashbacks in his gruelling ’78 opus.

Friendships forged in the steel mills of Shitwheel, Pennsylvania. Money earned for beer and broads, maybe also for firearms to perfect killing wild animals with a single pull of the trigger. Boom. One shot. Michael Cimino was instantly elevated to the status of Tinseltown deity in the mid-’70s due to the success of The Deer Hunter, his widescreen, minor-key symphony to the innocent, honest-to-goodness working class Midwestern dreamers who were packed off to ’Nam to become cannon fodder for Uncle Sam. If they didn’t return (at best) with missing limbs or (at worst) in a metal casket, most likely the wires up-top were well-and-truly frazzled.

Viewed today, the film comes across like Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused had that film contained a second act where Wooderson and co were all drafted into the US infantry then later returned to Austin to continue their annual hazing rituals while on heroin and with snub-nosed revolvers instead of hand-tooled wooden paddles.

Yet where Linklater’s film generates emotion from the bittersweet realisation that these characters will live on and develop after the film has ended, The Deer Hunter is novelistic and self-consciously epic, a self-contained tale in which things are said primarily through fear that the audience may concoct a reading which doesn’t square with Cimino’s lofty, all-encompassing vision of man’s fate. Know this: outside the timeline of The Deer Hunter and after the (sentimental) credits have rolled, nothing else of interest happens to these characters.

The prolonged wedding sequence at the start of the film remains its highlight, as it is the sole stretch of film where Cimino strains for realism rather than meaning. Indeed, these scenes smack of the democratised-likes of Robert Altman, not merely in the way the editing impulsively switches between characters and perspectives, but also the wealth of naturalistic background detail.

The best shot in the entire film is a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moment where the crowd are at one in frenzied elation at Angela and Steven’s union while an elderly couple sitting alone on the periphery of the hall and – seemingly unprompted – begin to kiss. Cimino’s knack for locating poetry in pure, swirling texture would come to full fruition two years late in by far his greatest achievement, Heaven’s Gate.

All the central characters are culled from a Russian-American community, which would appear from some angles to be a provocative choice of ethnicity. Though the musical repertoire at the wedding is predominately made up of Russian and Slavic folk songs, none of the characters seem so in touch with their roots that they might question the Vietnam war on an ideological level.

It’s as if the promise of America is enough subsume any overhanging political allegiances. It’s also interesting the way in which Cimino presents happiness and contentment within what is an outwardly dreary social milieu, with Nick even stating point-blank that he loves life in his hometown. There’s even an irony to the fact that it’s Russian Roulette that becomes the group’s death sport of choice.

Talking of which, there is a dark irony to the concept of a film about the dismal psychological effects that come from the viewing of extreme and ungoverned violence, and the fact that it is clearly one of the film’s aims to employ imagery and sound which will pummel the viewer into submission. Certainly, in a time when there’s a market value in the cinematic race for world-beating acts of revulsion – like Pink Flamingos gone blue chip — the much vaunted Russian Roulette sequences perhaps don’t repel at quite the same level they may have done to those for whom the thunder of war was still ringing in the ears. But they are earnestly staged and, of the many chapters in this three-hour feature, are protracted as a way to generate tension rather than ladle-on texture.

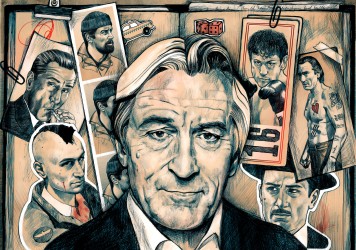

Though the film is essentially about the sudden dissolution of the aforementioned friendship, it’s Robert De Niro’s Mike who is the film’s central character, something which is mooted during the first deer hunt sequence when he dashes off for some solo shooting, and then confirmed in the final act where he takes on the task of attaining a post-war status update on his tragic pals Nick (Christopher Walken) and Steven (John Savage). This is not a work whose subtexts and themes are hidden particularly well, and Nick and Steven are shown as the sorry victims and in no uncertain terms.

It is, however, De Niro’s character who is, in hindsight, the most intriguing of the three, as he’s the one on whom the harsh legacy of war has imparted the least direct effect. His impulsive decision to spare the life of a deer later in the film may be the start of a new pacifist streak, but it’s strangely upsetting that a man could see all that he has seen and manage to conceal the psychological fall-out. Or, is his willingness to enter into a Russian Roulette bout with Nick as a way to lure him back home even more crazy than the listless suiciding of his smack-addled comrade?

Published 1 Aug 2014

Oscar-ordained ’70s powerhouse back under the spotlight.

Heart-on-sleeve stuff that works despite some of its more egregious impulses.

Its classic status has endured.

Francis Ford Coppola’s magnum opus gets a big screen outing, see it if only to be able to understand The Simpsons better.

By Matt Thrift

Dirty Grandpa may be an indefensible dud, but the actor’s recent output is nowhere near as bad as everyone seems to think.

A jaw-dropping spectacle and brain-melting existential nightmare, Francis Ford Coppola’s Vietnam opus is touched by genius.