A curious artistic experiment amounts to little more than that in this so-so Vincent Van Gogh biopic.

Anyone mounting a new biopic of “the father of modern art”, Vincent Van Gogh, must surely be aware of the fact that they’ve got some tough acts to follow. There’s the vibrant Technicolor psychodrama of Vincente Minelli’s Lust for Life from 1956, with a roaringly-pained Kirk Douglas centre-stage, as often chewing the scenery as he is painting it. Then there’s Robert Altman’s characteristically shaggy portrait of the dynamic between two brothers in 1990’s Vincent & Theo, adding Method to the madness of the Van Gogh saga. Finally, a year later, came the masterfully subdued (and best) account of the artist’s final days with Maurice Pialat’s straightforwardly-monikered, Van Gogh, starring French rocker Jacques Dutronc in the lead.

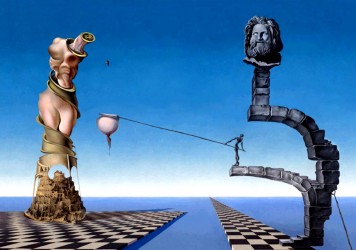

Yet surely there’s room at the table for one more VGV movie? With Loving Vincent, the Polish/ English directorial tag-team of Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman bring something new to the table, even while covering familiar biographical territory. Theirs is purportedly the first feature film to be painted entirely by hand, employing a team of over 100 artists to painstakingly tackle each individual frame. For a 91-minute movie that’s no mean achievement. At 24-frames-per-second, some 130,000 individual paintings make up the film. The effect is undoubtedly impressive. Using a rotoscopic technique familiar to fans of Richard Linklater’s A Scanner Darkly, flashbacks are rendered in black and white (charcoal?) while the present-tense meat of the narrative approximates Van Gogh’s own style.

Yet it’s hard to comprehend what such arduous toil is all finally in service of, given the major screenplay issues in evidence. The film’s drama is framed as a mystery, asking questions around the suspicious circumstances surrounding the artist’s death. An opening newspaper headline tells us that Van Gogh died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound in the fields near Auvergne. An appallingly-mockneyed Douglas Booth plays Armand Roulin, the son of a postmaster tasked with delivering one of Vincent’s final letters.

He’s not convinced that the troubled artist could collapse into suicidal agony in such a short space of time, and begins questioning those who knew the man in his final days. So we’re introduced to a series of characters, each taken from one of Van Gogh’s works. Roulin meets them, asks them a question about Vincent which cues a flashback of biographical monologuing, before bringing us back to the present-tense where the amateur sleuth moves on to another. And repeat. And repeat.

“What I’m wondering is whether people will appreciate what he did,” says Roulin at the end of the film. But Loving Vincent seems more concerned with the riddle of his passing than saying much about the artist himself, a ghostly presence in his own narrative. It’s a sensationalistic approach – did he shag Saoirse Ronan in that boat? – that sheds more light on the guilt of an opportunistic community than on the man himself. Perhaps that’s the point, but the tedious structure and Wikipedic dialogue illuminate about as much as a film that finally says Van Gogh’s art looked a bit like this.

Published 13 Oct 2017

The first animated feature film to be entirely painted by hand.

Aesthetically impressive, at first.

A sensationalist approach to the artist’s final days which ultimately illuminates little.

Gerda Wegener shocked the art world in the 1920s with her progressive and provocative paintings.

By James Clarke

In 1946 the moustachioed maestros embarked on the most ambitious project of their careers.

Meet the resident Da Vinci who turns candy into art at California’s notorious San Quentin penitentiary.