Cold exteriors and warm interiors combine in the Coen brothers’ rhapsodic portrait of a ’60s folk singer.

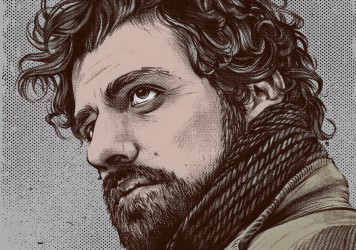

“If it was never new, and it never gets old, then it’s a folk song.” A warm ripple of laughter issues from the sparse crowd, diffusing the smoke-filled air as Llewyn Davis (Oscar Isaac) caps off another set at the Gaslight Café, a smoky fleapit in Greenwich Village, New York, circa 1961.

This opening quip is delivered at the end of a stirring rendition of folk standard “Hang Me, Oh Hang Me” which was recorded by real-life troubadour Dave Van Ronk – the Brooklyn-born singer-songwriter whose story part-inspired Joel and Ethan Coen’s toe-tappin’ triumph. It’s a line that neatly establishes the self-defeating cynicism that’s indicative of the film’s hirsute proto-hipster protagonist, who is imagined as an affectionate caricature of the kind of fame-hungry yet conflictingly anti-careerist performers who occupied the city’s blossoming folk music scene before Dylan got down in the groove.

It comes as a surprise to learn that Llewyn, who cuts a lonesome figure throughout, at one time made up one half of a promising trad-folk duo whose sole LP, ‘If I Had Wings’, has been steadily collecting dust in storage crates since his partner’s suicide. Llewyn has been on a downward spiral of sorrow and self-loathing ever since, his self-righteous, couch-surfing anti-establishment credo gradually wearing thin on the few remaining friends and family members still willing to take him under their wing. Having jacked in the merchant marines to go pro, his debut solo album, from which the film takes its title, isn’t selling well, much to Llewyn’s indignation. “You’ve got to give people time to get to know you,” his has-been manager unconvincingly reassures him. On the surface of it, though, why would anyone want to get inside Llewyn Davis?

The answer isn’t obvious, at least not right away. Llewyn isn’t an obvious addition to the Coens’ elongated line-up of beautiful losers, scoundrels and rogues, and the writer/director siblings are in no hurry to enamour us with this belligerent balladeer. His journey is pockmarked with minor setbacks, many of which are self-inflicted. As Llewyn picks his frets and sets the world to rights, it feels increasingly as if everything is conspiring against him. Every flaw is magnified and no indiscretion goes unpunished. Mistakes unfold in plain view, each new regret-in-waiting signposted in a language that only Llewyn can’t read.

In one standout scene Llewyn lays down a track at Columbia Records with fellow songsmith and close pal Jim (Justin Timberlake) and a baritone cowboy named Al Cody (Adam Driver), only to wave any performance royalties in favour of a quick buck having arrogantly written off the song as being too square to be a hit. “You’re like King Midas’ idiot brother,” scorns Jim’s partner (and Llewyn’s one-stop lover) Jean (Carey Mulligan).

Jean’s beef may come with a particularly delicate caveat, but even so, there’s no risk of Llewyn winning a popularity contest amongst his peers. Even a friends’ cat – written in, according to the Coens, though surely said with some degree of self-deprecating facetiousness, because the screenplay didn’t contain a plot – doesn’t hang around for long in Llewyn’s company, opting to brave the biting winter cold rather than wait to be returned to its owners. Despite being lifted by flashes of satirical humour and a tranche of typically quirky cameos (some of which feel recycled, but are no less effective), Inside Llewyn Davis is one of the Coens’ more inwardly melancholic offerings.

This is a film about sticking to your guns, even if that means alienating those who offer support. But while the Coens explore the indomitable nature of the American spirit, they’re also quick to establish a harsh disconnect between dreams and reality. Like so many struggling musicians working the same baskethouse club circuit, Llewyn Davis is treading water, his endearing self-belief smited by each fresh knockback. When Llewyn hitches a ride to a snow-blanketed Chicago in an opportunistic attempt to secure a record deal at Bud Grossman’s legendary venue, the Gate of Horn, there’s a fleeting sense that this could be his big break. As he makes the long trip back to New York, his despondency palpable, the feeling of terminal malaise that makes the Coens’ sixteenth feature so affecting is unavoidable.

It’s upon returning home that something clicks. Llewyn may yet convince himself that he is destined for great things, gold records and sell-out world tours, but for now, New York is where he belongs. The city fits Llewyn like a glove. Though he itches for something more, there is a part of him that is as settled as the clock-punching suburbanites he holds in such contempt. For now, this time and this place offer his best shot. And so he picks up his guitar and strums a familiar tune, thankful for the loose change but determined to continue stepping to his own beat. It’s a bittersweet coda that arrives right on cue, just when you start to suspect that, like its sailor-mouthed, angel-voiced antihero, this spiky tragicomedy has nowhere left to go.

Timing, of course, is everything, and something the Coens have a better grasp of than most. Their mastery of character and setting (whether period or present day) are nothing new, their ability to populate and colour instantly recognisable locales – be it post-war Southern California, Dust Bowl Mississippi or Space Race-era NYC – while avoiding the more obvious landmarks and cultural reference points is consistently gratifying. Irrespective of the where and the when, there’s a soothing familiarity about the worlds they create that’s as unwavering as their dry observational wit. Like slipping on an old pair of jeans, everything fits just the way it should.

In Inside Llewyn Davis this effortlessly applied realism is reinforced by long-time Coens collaborator “T-Bone” Burnett, Bob Dylan’s old touring guitarist who produced the soundtracks for O Brother, Where Art Thou? and The Ladykillers, here working alongside Marcus Mumford, who earns himself some serious cred for his lyrical and vocal work. Performed live by Oscar Isaac in spine-tingling close-up, the songs selected for the film are gutsily played out in full, and frankly it’s no wonder when they’re so infectiously, soul-nourishingly good. If the songs linger longest in the mind, however, it’s only because the Coens have built such a robust player on which these glorious platters can spin. They say that the best songs are the most simple ones. Well, as far as the Coen brothers are concerned, no one makes simple look so easy.

Published 22 Jan 2014

Any new film by the Coen brothers is an instant must-see.

Funny, charming, surprising, heartbreaking. Play it again, maestros!

And again, and again, and again...

The Coens are back and have brought every one of their celebrity pals with them.

The Inside Llewyn Davis star chats to LWLies about getting into character for the Coen brothers’ latest.

Two men, operating as a single creative body. Little White Lies was offered a rare audience with the Coen brothers.