Michael Mann returns with a majestic B-thriller which offers a sharp commentary on the mass digitisation of communication.

In box office terms, what Michael Mann’s Blackhat did in the US early in 2015 was equivalent to swan-diving into a swimming pool that didn’t contain any water. The pulpy mess was hosed away quickly and quietly, causing some commentators to suggest that this would be the last time Mann would be able to command such a serious budget. As such, the fanfare surrounding its UK release is muted to say the least, the sound all-but drowned out by omnipresent award season gabbing. Over here, it’s less a pool, more a shallow puddle.

Yet there’s a strange paradox at the centre of Blackhat. On one hand, the film offers ample pleasures to those willing to pick at its complex design schematics, specifically its innovative use of digital photography which reflects Mann’s connoisseur-like abilities to select the right tool for the right job. On the other, its archly dismissive attitude towards conventional plotting and stock showmanship make it tough to decipher whether Mann views his movies as portable museums to house a breathtaking collection of style tics, or whether the job of fulfilling audience expectation is just secondary for him.

Alternatively, is Blackhat’s commercial failure in actuality a veiled victory for sensorily-inclined aesthete Mann, or was there an intention for the film to slot neatly into the cash-grabbing neo B-thriller template forged by Liam Neeson and the Europacorp jet-trash? If Mann were no longer able to command top-end budgets, would that really be such a bad thing for the people he appears to be making movies for?

During the Sony hacking scandal of late 2014, it was noted that the orbiting furore was possibly/probably more interesting that the subject that caused it, the button-pushing comedy feature The Interview. This stranger-than-fiction occurrence ended up being the stuff of shadowy ’70s-style conspiracy thrillers, and the intricacies of who won, who lost and who was even playing the game remain opaque to this day.

In the same way, Blackhat is less interested in handing us a cackling Joker-style villain and observing a wily game of cat-and-mouse than it is leaving us to ponder exactly who or what is the malevolent force causing all this wireless destruction. It’s a film which is interested in spectacle, but only within the context of reality. Oftentimes, reality is the spectacle, depending on how we look at it. Computers mean that we no longer know who the bad guys are, or that bad guys don’t have to have a public (and by extension, cinematic) persona, and movies that paint in those crude shades are simply wrong. Yet even though computers are shields, they can be penetrated.

One criticism levelled at the film is that it contains too many shots of people sat down at computers and typing. Which, without meaning to generalise, would seem a somewhat hypocritical judgment. It’s true, the film does contain shots of keys being tapped, code being forged, monitors flashing with abstract, two-tone compositions of character formulations and frames within frames. If anything, these moments are what make Blackhat feel entirely relevant and contemporary, a statement on the large-scale atomisation and mechanisation of human processes.

Where a traditional heist — such as those that made for breathless centrepieces in films like Heat and Public Enemies — would’ve once involved bodies and bullets, crime is now characterised by banality, ease and progress bars. Electronic synapses have replaced guns, but the latter still do come in handy, and are still very loud. Another criticism is that Mann has reached a point where he’s Xeroxing his own work, and if that is indeed the case, then there’s a certain poetry in the idea of a filmmaker resorting to the Apple-C, Apple-V function at the service of a thrilling commentary on absolute digital consummation.

When it comes to shooting on digital, Mann could be seen as something of a pioneer. The gripe that it “doesn’t look like film” has bypassed him completely. He accepts what it does look like and duly attempts to capture images that synch up with digital’s singular visual constitution. On occasion the film resembles blocky video art, with the compositions verging on the abstract. Although Mann embraces these qualities, Blackhat also concerns the ultimate fallibility of technology, with its combustible final image leaving a question mark over how far the medium has to come to attain perfection (perhaps also suggesting that, while many are happy to allow their lives to hang in the balance of the internet, there’s still hope if we want to get the hell out).

There is a heist sequence in Blackhat, though it doesn’t involve any people. Mann imagines what a heist would resemble in a world where the physical has been displaced by the digital. It initially recalls so many ancient Intel PC TV advertisements in which the goal is to depict the manifold functions of the microchip and somehow emphasise its world-conquering properties. The “camera” begins its journey by hovering in the stratosphere, surveying a planet verily a-glow with golden communication tendrils.

Then it dips down into a Chinese nuclear facility, through the waters of the cooling tank and then down into the motherboard of a vital component: an electronically powered pump. It soon becomes clear that the camera isn’t there to survey the mechanical innards, but to follow the course of a malware programme uploaded by some unknown cyber terrorist. It’s a masterclass in visual storytelling, with barely a word of dialogue uttered until meltdown is duly instigated.

Enter Chris Hemsworth and his monster bangs, on lockdown for a cyberhacking rap and filling the hours doing gravity-defying knuckle push-ups. He’s given conditional release because a Chinese investigator (and old college pal) believes he’s the only one who can track down the mystery hacker. The film then stacks up the set-pieces which are linked with fuzzy GoPro interludes and the customary neon-grilled night vistas.

Hemsworth gets to snuggle with Tang Wei, while from the sidelines, Viola Davis casually walks away with top acting honours for her hard-boiled FBI stooge whose government-mandated supervision gradually takes a turn for the Stockholm-y. It’s easy to dismiss Davis’ character as peripheral — a plot crutch — for much of the time she’s on screen, only for her to eventually appear in the film’s most nakedly moving shot prior to the final act showdown. It’s not possible to say what it is, but rest assured: it’s devastating.

Maybe it’s too cute that Mann would reach his digital apotheosis in a film about cyber terrorism, but he proves this technology is still in a state of flux, waiting to be amply harnessed. Blackhat suggests that the world could be crumbling and we wouldn’t even notice it, with billion-dollar battles fought via text message and GPS satellites showing exactly where the sniper should perch for the cleanest, easiest shot. When the day finally feels like it has been saved, Mann then flashes up that haunting final shot, reminding us that we’re just a one burnt-out microchip away from total annihilation.

Published 20 Feb 2015

America said an emphatic, “no thank you!”

With each new film, Mann’s past films look even more interesting and abstract.

Much cybercandy here to chew on.

By Fred Wagner

Oliver Stone’s Snowden will look to realistically show the actions of the NSA and other government agencies.

The John Wick: Chapter 2 director and onetime stunt double reveals some of the secrets of his craft.

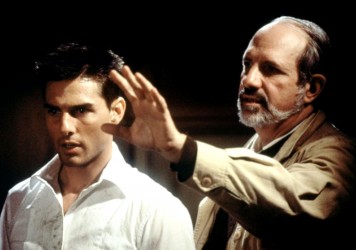

Twenty years ago Brian De Palma and Tom Cruise ushered in a new blockbuster era.