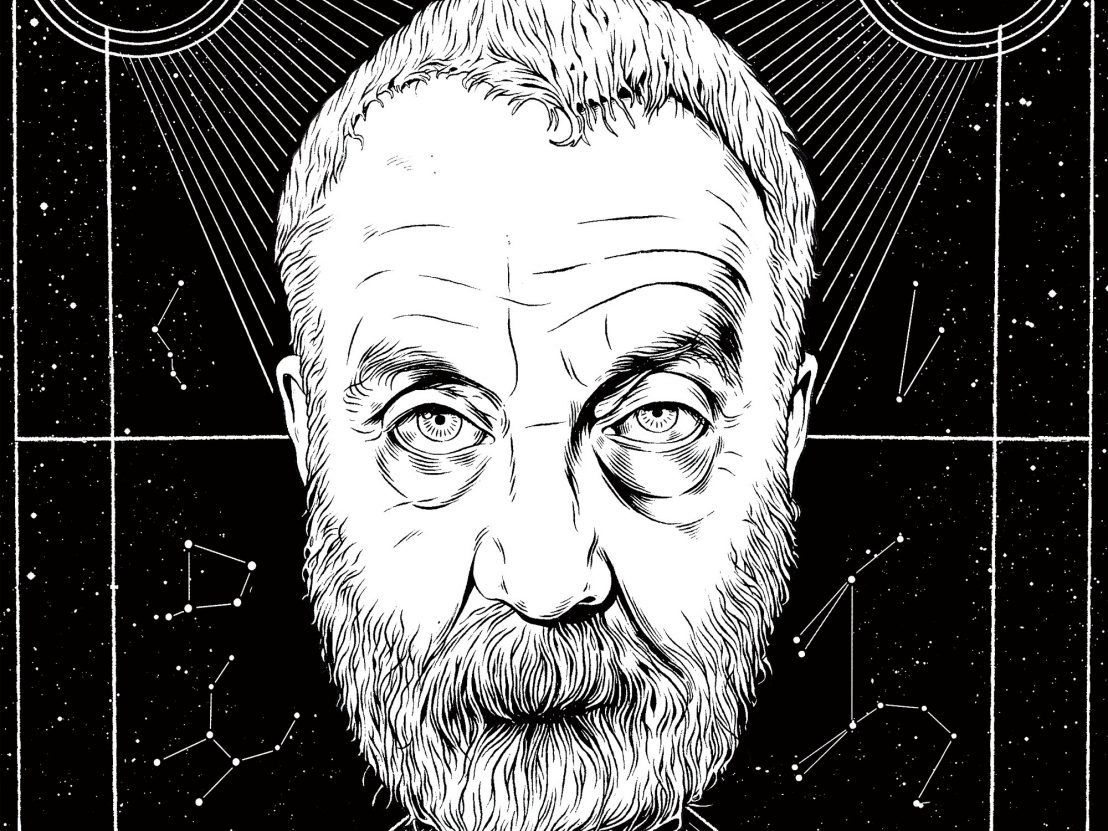

LWLies sits for the British cinema icon who doesn’t mince his words to talk Mr Turner.

Mike Leigh has a reputation for being spiky in interviews, so it was with moderate terror that LWLies sat down with the 71-year-old British maestro to discuss the ins-and-outs of his astonishing new work, Mr Turner.

LWLies: Mr Turner is a film where death looms large but by the very act of making the film you’re resurrecting a life that clearly has meaning to you. To what extent do you think that we can, through art, make people live forever?

Leigh: I don’t think we can make people live forever. Turner is dead. He died in 1851. His work lives. We’ve created a world, a character. We evoked something. On the one hand, I’m quite sure that if you get into a time machine and go back to the actual events they, in many respects, would bear absolutely no resemblance to what’s on the flickering silver screen. On the other hand, we, and you – the audience – enter into a conspiracy to say that we are bringing something to life. That’s what we do in films anyway. Even if I make the whole thing up, as I usually do. You’re still bringing something to life that actually doesn’t exist. What’s important is what we experience from it and what we gain from it, what we share about it.

Where does the extensive concentration required to create come from?

It’s hard to answer a question like that without – and I’m cautious here – without running the risk of sounding deeply pretentious because the fact is that an artist of any kind has to be driven, and has to be driven by some sense of something that goes beyond simply, a thing that is very important but nonetheless which is just the practical fact of doing it. So there’s going to be something spiritual and telepathic, whatever you call it, I hesitate to call it divine because I think that would be over-stating the case but all that has to be going on at some level but what is that? That is only about having your antennae attuned to stuff that’s going on on different levels.

So you’ve got your antennae up to purely an idea and then you’ve got to transform into something that translates to the screen.

Well that’s the name of the game! And that’s what Mr Turner is about! There you see a guy who can see and experience profound and epic things but actually what you see all the time is a guy mixing paints and lugging things about and doing practical things which is what we call making paintings. Nothing is more practical and prosaic than the mechanics of filmmaking but the job is to take all of that and all of those people involved in it and somehow go beyond the mere technicality of it and create something that looks at the world and distils something from it but in a way we’re not saying anything that’s not obvious really.

The mechanics of filmmaking in this case involved the goal of recreating some of the scenes within Turner’s paintings and drawings…

We’ve been inspired by his paintings in how we’ve rendered and made things look. To begin with it’s about looking at and understanding and getting to know his work and coming to understand where he was coming from…

Do you remember the first Turner painting you ever looked at?

When I was a teenager a million years ago in the 1950s, I, now, thinking back on it, was pretty vague about Turner and indeed Constable and all that. By the time I was 14 or something I really knew about Picasso and the impressionists and 20th century art and even surrealism and Salvador Dali. All of those things were pinned on my bedroom wall as postcards but Turner was vague. Was it something on chocolate boxes? I don’t know. But it wasn’t until I was at art school a few years later that I started to look at him and understand. And I don’t know what the first painting was but I know that I started to go to the Tate and the National Gallery and see the paintings and become aware of what he was about.

Presumably there was then a gap of some years before you decided to return to Turner…

It was only in about 1998/9 that it suddenly hit me. Have you seen my film Topsy-Turvy?

Yes.

After we’d done that somewhere along the line it started to occur to me… because until then I hadn’t really done a period and once I’d done Topsy-Turvy I realised you could do that. So then I started thinking and reading about Turner and I realised that the, again, what I’ve already referred to about the tension between the character and the work, it all came together. And apart from anything else there isn’t or hasn’t been a motion feature film about Turner so I though maybe we should do one. The next thing was a decade or so of trying to get the money to do it because it needed to cost a lot more than we normally get to make my films when you just see people arguing on staircases and in back gardens…

And cafes…

And cafes. Absolutely. But in the end we didn’t get really as much as we wanted and in the end it was made for less than Topsy-Turvy so that was the big struggle. While that was going on we were constantly researching and reading and building up ideas. When it came to actually doing it then it was about casting it and looking for locations and all those things.

Was Timothy Spall always going to be your Turner?

He was the only actor I asked. And once I’d thought of him that seemed very logical. Partly because, apart from anything else, Turner was very much a Londoner and there’s something in what Tim knows as a Londoner that he would have to tap into. I also knew he had a certain amateur predilection for drawing and painting.

In your film he communicates through an extraordinary array of non-verbal sounds…

That came in the first place from what we read about Turner. He did grunt. Somebody had sat down and transcribed him actually talking so that was quite useful. It’s an attempt to try and get at how he talked.

What do you think words can do that sounds can’t?

An equally interesting question is, ‘What do I think sounds can do that words can’t?’ People talk about language and words. What I’m concerned with in a film, and this film is no exception, is the total combination of elements that make reality. It’s what we say and it’s the space between words. If you listen to where we are now its incredible, there’s an incredible amount of soundscape going on in this room. And also there’s what we’re saying, how we’re saying it, what our subtexts are, what happens in the pauses but also part and parcel of all that is me as a character, you as a character, where we are, what the dynamics of our relationship is, what I’m wearing, what you’re wearing, what I think about you, what I wonder about you, what you wonder about me. All those things, the whole history of what leads to this moment and what I do in all films – including this one – is an incredible amount of work that leads up to a moment so that moment resonates with reality so that it’s the tip of an iceberg, as in real life. So the question about sounds, words, silences, articulacy, all those things, I see them all as part of an organic whole and you can’t separate them out. They’re all different elements that have to be dealt with.

Do you think – and this is just an off-the-top of my head theory – do you think that words are a way of interrupting and rationalising emotions?

That is, if you’re serious… well, you say it’s an off-the-top-of-your-head theory; it sounds like an off-the-top-of-your-head theory.

Sorry!

You can’t seriously be suggesting that by definition words dilute feelings or disguise or camouflage feelings or truth or meaning because that is altogether a highly reductionist over-simplified thing to say. Of course, they can do that but to say that they do do that would be very dangerous.

So how do you find this part of your job – talking to people that ask you lots of questions; some bright and some not so bright?

Unless it’s irritatingly stupid, which this isn’t… or irrelevant… I mean, look, here’s a thing. You make a film. We finished this film at the beginning of the year. Until I went to Cannes I didn’t really have to talk at all about it to anyone. Then all of a sudden you get dropped in this mayhem they call Cannes and you’ve got to do a massive amount of press. Now, what is happening there to me is I’m at the beginning of a journey of finding out two things. One is how to talk about this film and two is learning what it actually is that I’ve made. That involves a whole bunch of conversations with all kinds of people. And I love conversations so we’re having a conversation. You’re hardly the most predictable journalist I’ve met so it’s great.

Who matters most: the response of the public, the response of fellow filmmakers or the response of the press?

It all. Anyone that says, ‘I don’t care what anybody else thinks’ is lying. Positive responses can only be good news. It makes you feel like you haven’t been wasting your time. It’s stimulating. Also, apart from anything else, I have this ticket to conversations with people and I go to film festivals where you get fed and watered and you meet audiences. I make films for audiences. There are people that make films and they don’t want to talk to anybody. I mean there’s a level of sometimes you think actually it would be great just to make a film, walk away and make another film and not have to do all of this. But that’s only because it gets repetitious or it gets too much or it encroaches on your time but in real terms, part of the joy and the point of doing something – which by definition is about communicating with people and sharing with people – is the feedback, which is as important as anything else. Indeed the feedback feeds back. I hope it makes me a better filmmaker in some way.

Is it too early for you to be thinking about your next project?

I have other things I have to do. I’m going to direct a production of The Pirates of Penzance next year in May for the English National Opera so we’ve been working on that, designing it and so on.

I know it’s not autobiographical by any stretch of the imagination but I’m curious to hear what it is about him that is your conduit?

He took no shit from nobody so I identify with that.

Have you always been a no shit-taker?

What do you think…

Published 29 Oct 2014