The German writer/director reveals how she quietly went about making one of the great films of the 21st century.

Following the 2016 Cannes world premiere of her third feature, Toni Erdmann, German writer/director Maren Ade became an instant celebrity. The film concerns a father who goes to absurd lengths to regain closeness with his daughter. Its maker spends years gestating ideas, playing the long game of producing only a few, highly-refined movies a decade, as opposed to cranking them out annually. Her features, to date, reveal an interest in character dramas powered by observations on the bungling ways that humans – sometimes comically, often painfully – try to connect with those closest to them.

Her debut The Forest for the Trees, from 2003, is a deadpan study of adult loneliness and alienation channelled through wide-eyed, well-meaning schoolteacher, Melanie Pröschle (Eva Löbau). The more desperately Melanie tries to find a companion, the more it eludes her. To compound this, her total inability to read social cues leads to a string of excruciatingly awkward rejections.

Later, in 2009, came Everyone Else, a meandering summer story about Chris (Lars Eidinger) and Gitti (Birgit Minichmayr) who are sexually compatible but struggle for mutual understanding in other areas. The abiding enigma of whether they will stay together or drift apart makes for an open ending that holds answers without giving them away.

Read more in LWLies 68

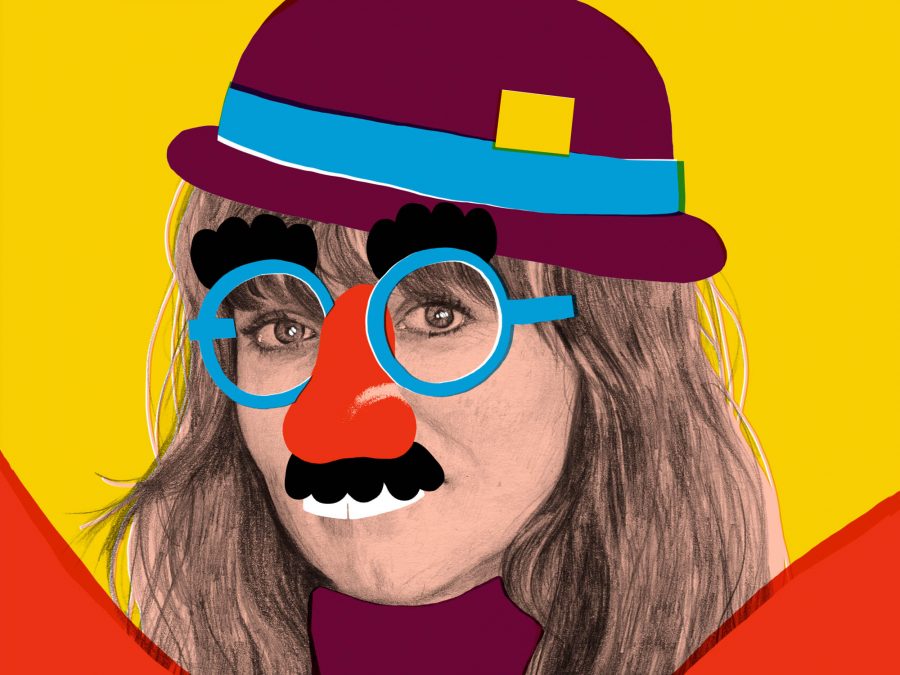

Get the magOn to the film that transformed Ade from a respected arthouse director to an exalted icon of the scene: Toni Erdmann. Deserving of its plaudits by virtue of masterful pacing that causes three hours to fly by in a throng of hilarious situations that move towards a hard-won harmony between a father and his daughter. When we meet Ines (Sandra Hüller) she is a stressed and serious businesswoman, who is only exasperated when father Winfried (Peter Simonischek), camouflaged in false teeth and a wig, begins introducing himself to her colleagues under the alias ‘Toni Erdmann’.

Undeterred by his daughter’s reaction, Winifred persists in long-haul pranking. Simonischek’s physicality – hulking yet poised, with dark eyebrows that sit under white hair – contributes to an air of good-natured buffoonery. Performance wise, Hüller is tenser and tauter, but the pair share a certain restraint that reveals a subtle sense of the unspoken respect pulsing between them.

We spoke to Ade back in October 2016 on the day of her BAFTA Screenwriting Talk during the BFI London Film Festival. Interviewing her is a complex pleasure, one that offers the opportunity to mine her rigorous technique and emotional savvy. It leads to an understanding of how form influences content, creating a fascinating reflection of the interests buried within her films.

LWLies: You make films about the complexity of human relationships. Does it make those relationships any easier to handle in real life?

Ade: A film for me is something that shows what I was thinking about the last five years, or sometimes three or six years. I discover things about myself. The films transform with what happens in my life. You cannot say it’s like this or that because I had this or that experience, it’s more that it gets richer the longer or the deeper I go into a topic. It feels like digging a hole and I come out somewhere else in the end. But actually, it’s also sometimes very stupid. With Toni Erdmann, for example, I’m doing a film about a father/daughter relationship and I don’t have any time to call my parents. Doing a film like that you could also become like Ines, so you have to be careful. There’s always a risk.

How do you give yourself over to making your films good while keeping life good?

That’s the thing. Films sucks a lot of energy out of you. When I do a film I give up part of my own life and that’s not always nice. That’s why it takes so long [to put out features] because I try to put a relaxed life in between. I have two children now, aged one and nearly five, and that’s a very good thing because there’s no discussion, you need to be in the moment with them.

When you’re dedicating yourself to life, does it get to a point where you grow restless to make your next film?

The moment I start doing something or the moment I have an idea I feel I will always go until the end. So, I said to myself that I really want to take a break now, after Toni Erdmann, just for a year or something. I finished the film with a small child, now and I need some time. I said to myself, ‘I’m not allowed to start writing something down’ because if I start I will continue. But actually there’s a lot of joy to making a film. There are so many different phases and not every phase is equally tiring. With the writing, you’re very free in how you spend your day. And with editing it’s the same. It’s just this thing in the middle – the shooting – where it feels like you go on an oil platform. You’re completely gone.

Do you remember where you were when the idea for Toni Erdmann landed in whatever form?

I don’t remember that. It goes back very far because since a long time ago there was an interest in doing something about family, or family structures.

What was that interest in family structures inspired by?

By my own family. My father is someone who also likes to joke. He has a good repertoire. It always interested me what he’s doing with this approach to life – to solve things with humour on one side and, on the other, how people react to him. This family thing is always an interesting topic because it’s a lifelong relationship so it’s very heavy. It’s hard to escape these roles. You don’t know where they really come from. It goes back so far into childhood.

If you’re naturally fascinated by a subject, that’s a good motor for you to address it in a film?

That’s good. ‘Naturally fascinated’. [Ade makes a note] That doesn’t personally interest me but beschäftigen… where I feel the need to say something about it that emotionally drives me.

What is ‘beschäftigen’?

Beschäftigen is things that you think about a lot.

Like obsessions or fixations?

Nah, that’s too much. It’s in between thinking and being obsessed. Sometimes in different languages you don’t have a word.

At what stage in the writing process do you bring in other collaborators?

I’m writing alone and I enjoy that very much. [Ade makes a note.] ‘Writing alone’ is good. I’m sorry! I’ve got that BAFTA talk and I didn’t prepare the intro so during the interview when something comes into my mind I have to write it down. So, I enjoy writing alone, but at a certain point I show it to several people and I also have one, the actress in my first film, The Forest for the Trees, who played Melanie Pröschle, the teacher? She’s a friend and she was a dramaturgy consultant on Toni Erdmann. We met and talked about what interests us, our families and the script. I always alternate between being alone with my subject and my script, and then I open it to the rest of the world – I go out, I do research, I give it to people, I try to see films. When I’m writing I’m completely into it and I’m trying not to analyse it.

That’s great, so you don’t judge yourself when you’re writing?

Yeah and that’s what’s important. I really try not to judge myself and I try to write down everything even if it feels stupid or not serving the plot or the script. Even if it’s like a completely different idea that maybe doesn’t really fit in at first sight. I try to be creative, you know?

You have these two big, rich characters in Ines and Winifred. How do you build up smaller characters and make them compelling?

I try to be equally interested in them as in the main characters. Actually, I think it comes out of the fact that I’m interested in the characters and not in the plot as much, so I’m thinking of working out of the situation – ‘What is the biggest need for a character in this situation, even if it’s a side character?’ and, ‘Where does he come from?’ and ‘Why is he saying what he’s saying?’ and ‘What is he hiding?’ This is the story for me. The story is not, ‘How do they solve the problem they are discussing?’ It’s more the dynamic between two characters. It’s always about hierarchies or the status between characters.

Do you let yourself be influenced by your collaborators once you’re building a crew and once you’ve cast your characters?

The actors always bring something in so you have to work with them, for sure. But with Toni Erdmann and all my other films, although they feel improvised, it’s 95 per cent a written script. The actors learn the dialogue. The dialogue is something that I try to make as natural as I can. It’s something that I hear.

Is that because you listen to people?

I don’t know. Maybe. I don’t know if I’m such a good listener. At a certain point I allow the actors to improvise a little bit and then I feel, ‘Ah no, it gets unprecise, so please, let’s stay with the script.’ Sometimes I’m so obsessed that I let the assistant control each sentence so that we’re really sure that nothing is forgotten. Improvisation always makes things longer, and often the actors have the feeling that they have to be inventive and that they maybe have to put emotions into the dialogue. That’s something that I don’t like so much. I like it more when the emotion happens on a sub-level and the dialogue is often very banal.

Something that’s fascinating about your films is that at the same time as you’re showing very naturalistic situations, yet there’s always emotion underneath it.

That’s a process. The dialogue and the staging is something that I prepare with the actors before the shooting day. That’s something that is planned. They learn the text. We meet before. I try to always get a rehearsal on every location, which is really important. Directing is so often just about arranging people, chairs, glasses and a camera until you really come to the point where you can work on emotions. It takes a while and sometimes you don’t have enough time for that on a shooting day. I try to leave something open for the shooting day to be able to surprise the actors with ideas of what happens on the sub-level. The sub-level work is tiring for everybody because, for me, it works better when you have to repeat it more often as it’s much harder to hit.

The thing with directing in general is if you say how you want it to look, in the end you almost never get that result. If you have a very good actor, he can do that but imagine you say to someone, ‘You sit there and feel sad.’ Imagine how you would play that yourself. You would sit and play sad. [Ade mugs exaggerated sadness]. Sometimes you need adjectives to direct. You nearly always need to find a better reason for the actor, and it’s good when you have an active verb, where it’s really something going on inside of someone. Like saying, ‘You’re not sure if you’re going to leave’, ‘You’re afraid that you might start crying’.

I like when a scene is rich on the sub-level. I think that we often do things that we don’t want to do. For example, Winfried, he buys that cheese grater and he knows it’s a very bad present. It’s the fifth bad present he has bought, and he knows all about this present, but still he has to go through and give it to someone. Immediately, you have a much more complicated scene. With that scene it seems very simple. She gets a present from her father. She should be happy. It’s nice to get something. Still, it’s very annoying that it’s a cheese grater. She’s not saying it. With family so many things are ritualised. People cannot escape. There was always a conflict going on.

When you describe the cheese grater scene it sounds so melancholic, but then it’s so funny.

For us in the end, yeah, but for them it’s not funny! With a scene like that, it’s just the fact that he’s giving her a cheese grater and the dialogue that is funny, that he’s saying the flight was cheap, cheese grater and that’s it. It’s not a funny scene. Definitely not when we were filming. Maybe watching it behind the video monitor I have a feeling that it will be funny in the end but in the first place it’s painful.

Is it funny for you that Toni Erdmann is categorised as a comedy?

Yeah, he plays comedy in the film but the reason he’s doing it is completely drama. It’s very desperate. He’s doing what he’s doing out of desperation and it’s the same for Ines. I’m happy that it’s a comedy.

Published 30 Jan 2017

Say hello to your new favourite movie as we pay tribute to Maren Ade’s tragicomic masterpiece.

Before you see Toni Erdmann, seek out the director’s brilliantly observed second feature from 2009.

Read part one of our countdown celebrating the greatest female artists in the film industry.