Rare works from Satoshi Kon and Osamu Tezuka were presented at this year’s festival.

Hidden inside the London East Asian Film Festival’s programme was a rare treat: three animated features celebrating the centenary of the birth of Japanese animation, an art form that has since grown to become one of the country’s most important, valued cultural exports. Anime has always had a certain eccentricity about it (think of some of the stranger sequences in touchstone titles like Akira or Ghost in the Shell, or anything at the edges of the output of supposedly child-orientated Studio Ghibli), but the films which LEAFF selected to honour the medium’s milestone take this eclectic, imaginative approach to storytelling to new levels, loosening the limits of the logic of reality, and travelling through the very fabric of space and time.

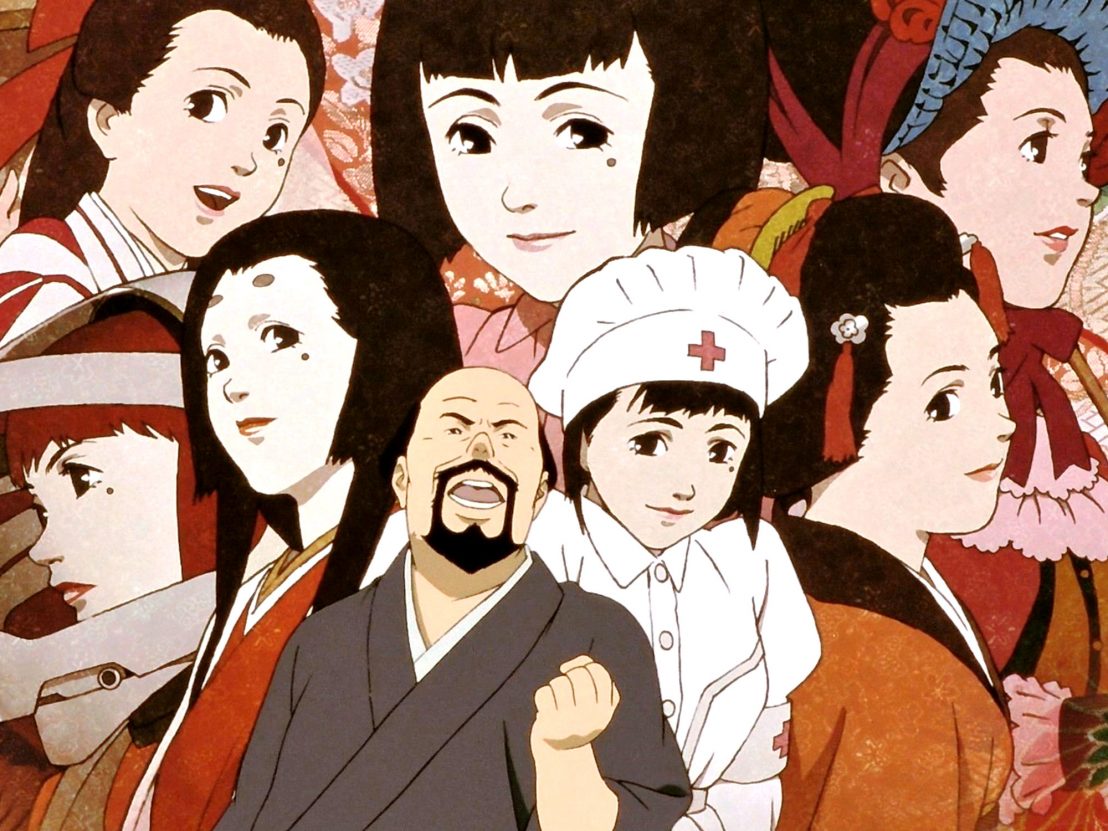

Their first selection was the most well known, Millennium Actress, a 2001 film from recently departed, much missed director Satoshi Kon (Paprika, Perfect Blue), one of the form’s true visionaries and inspiration for a great many filmmakers in the animation world and wider. A film about film, Millennium Actress begins simply – two documentarians interview a reclusive former actress about her career, probing open up a chasm of memories that she had buried – before unfolding into something more complex, a meta-cinematic, hyper-referential puzzle about the entanglement of life and art, a fever dream of cycling subjectivities and blurred boundaries.

Kon makes incredible use of the freedom and mutability of his animated canvas. The film’s colour palette mutates from monochrome to increasingly saturated colour as time advances, scenes morph one into another in a mix of colours, shapes and matter, and everything passes with a remarkable, often breathtaking fluidity, crossing between styles and eras seamlessly, and constructing a pandora’s box style, multi-strand narrative that all fits together with surprising clarity. A profoundly ambitious film that entirely meets the demands it sets of itself, like the best films in the format, Millennium Actress is a masterwork that could only exist as animation.

Similar in conceit but far more surreal in execution, Masaaki Yuasa’s 2004 film Mind Game also begins with a straightforward scenario before spiralling wildly outwards from it. In the film’s opening scene, a man brashly enters a bar brawl only to find that his opponent is packing heat. The foe opens fire, and things get weird. The debut feature from one of Japanese animation’s most iconoclastic and exciting voices, Mind Game is precisely what its title suggests, an expressionistic, freeform and frequently bizarre headtrip of a film.

Facing death, the film’s protagonist is given a second chance, killing his aggressor and initiating a chase sequence that ends with him and his companions entering the belly of a whale, home to a mysterious man who has lived there for an eternity. Little that occurs after makes any objective sense, and an overall meaning – other than the oblique directive presented by the film’s tagline, ‘your life is the result of your own decisions’ – is hard to deduce. Unlike the journey presented by Kon’s film, where engaged viewership and active interpretation proves rewarding, this trip is best enjoyed abstractly, letting Yuasa’s psychedelic visuals, bright, painterly colours, and bouncy, energetic soundtrack wash over.

The last film was another time-warp, though this time not so much surreal as entirely unhinged. Co-directed by Osamu Tezuka (Astro Boy, Metropolis) and Eiichi Yamamoto, maker of the recently rediscovered and reappraised erotic animation Belladonna of Sadness, Cleopatra was never released in the UK. A genuine oddity – part surrealist retelling of the story of its title character, part brash pornographic comedy – the film, though not entirely without merit, is unlikely to be reclaimed as a lost masterpiece of the medium.

In the weirdest act of teleportation in all of the three animations at LEAFF, Cleopatra begins with a crew of future space travellers being sent back through time and space to ancient Egypt to inhabit the bodies of various characters peripheral to the “Queen of Sex”, to witness her attempt to seduce and assassinate Julius Caesar. Cleopatra features a strange mix of the oddly artful, such as the abstract, minimalist linework in the impressionistic sex scenes; and the entirely puerile, with plenty of randomised cartoonish nudity and course, broad humour. Fans of animated esoterica will find something in it, but most viewers will leave confused.

It seems slightly short sighted that a celebration of 100 years of Japanese animation contains two films released in the 21st century and nothing made before 1970. However, these three films traverse more ground than might be first thought. Between them they travel far further than even the cinematic century could, exploring a history stretching way back before the medium’s origin, diving into subconscious territories, and flinging forward into future and imagined worlds. Why try to surmise history when you can invent it?

The 2017 London East Asian Film Festival ran 19-29 October. Cleopatra screens again on 2 December as part of the London International Animation Festival. Other works celebrating the centenary of Japanese animation can be viewed online on the website of Japan’s National Film Centre.

Published 2 Nov 2017

Rare shorts from 1917 to 1941 are now streaming in celebration of 100 years of anime.

Satoshi Kon’s cult anime contains a vital message for modern audiences.

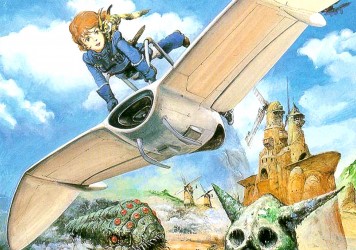

Gorgeous original artwork spanning three decades of the iconic animation studio.