Steven Spielberg’s alien invasion epic offers a boldly personal take on a contemporary global crisis.

Tom Cruise has been many things – bartender, hustler, maverick, self-help huckster, super-spy, unicorn whisperer and vampire to name a few – but before 2005 he’d never been a dad. At least not in any real sense. The closest he’d come on-screen was 2002’s Minority Report, but his character’s son appears only briefly in flashback. Which meant that when War of the Worlds was released in the summer of ’05, audiences had no preconception of Cruise as a parent – it opened a month after he gave that Oprah interview but a full 10 weeks before Cruise and then girlfriend Katie Holmes publicly announced they were expecting their first child.

If the role of Ray Ferrier was at the time anomalous in Cruise’s career, however, the opposite was true for director Steven Spielberg. Fatherhood is a recurring motif in virtually all his films, from the first true summer blockbuster, Jaws, right through to The BFG. Spielberg himself has spoken about how his own father’s emotional distance affected him as a child, and he continues to consciously explore themes of paternal absence, neglect and reconciliation in his work. But unlike E.T., Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade and Hook, each of which gauges the impact of the estranged father figure from the child’s point of view, War of the Worlds is told from the father’s. For all Cruise’s known qualities as an all-action A-list movie star, his tacit paternal inexperience played a big part in the film’s success.

Kathleen Kennedy, one of the producers on War of the Worlds, has since recalled that Spielberg told her not to “freak out when you look at the script. Just recognise that there are three people in the movie – that’s the heart of the film, and every now and then 1,000 people are running around in the background.” Indeed, you could remove the aliens altogether and the core of the story – what it’s really about – would remain intact.

Ray is a divorced blue-collar docker who must literally save his two kids, Rachel (Dakota Fanning) and Robbie (Justin Chatwin), in order to repair the ruptured bond between the three of them. In the beginning, he’s depicted as hard-working, inattentive and tetchy. When his ex-wife (Miranda Otto) and her new partner (David Alan Basche) drop Rachel and Robbie off for a routine weekend visit, Ray immediately assumes the role of patriarch despite the fact his kids are quite obviously not emotionally, financially or spiritually dependent on him. He’s aware enough of what a father’s basic duties are, but seems fundamentally incapable of carrying them out. When he coerces Robbie into a game of catch in the backyard of his modest New Jersey home, the gulf between them feels insurmountable even though they’re stood just a few metres apart.

Then the sky turns black and the air becomes heavy with trepidation. Suddenly you sense this might be Spielberg’s darkest film. This abrupt tonal shift is foreshadowed by an ominous prologue, in which Morgan Freeman’s narrator paraphrases the opening lines from HG Wells’ source novel: “No one would have believed in the early years of the 21st century that our world was being watched by intelligences greater than our own; that as men busied themselves about their various concerns, they observed and studied, the way a man with a microscope might scrutinise the creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. With infinite complacency, men went to and fro about the globe, confident of our empire over this world. Yet across the gulf of space, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic regarded our planet with envious eyes and slowly, and surely, drew their plans against us.”

Ironically, no one has done more to soften the image of extraterrestrials than Spielberg. In Close Encounters of the Third Kind and E.T., the aliens are benign, cuddly creatures that reflect the more virtuous aspects of our own nature; here they’re the stuff of nightmares, the kind of creepy, bug-eyed freaks that would make even HR Giger’s skin crawl. These strange, hostile invaders are a nod to the films of Spielberg’s youth, but just as the ’50s golden age of big screen science fiction – an era of flying saucers, space monsters and exclamation marks – was an indirect expression of Cold War anxiety, the aliens in Spielberg’s film represent a distinctly modern threat.

‘The War of the Worlds’ has been adapted on numerous occasions, always at the point of actual or impending international catastrophe: Nazism was threatening peace in Europe when Orson Welles delivered his legendary radio play to millions of terrified Americans; the original 1953 film arrived amid an air of palpable unease about the possibility of a nuclear holocaust. In 2005, a US-led coalition was locked in a bloody stalemate with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq regime, and back on home soil people were still fearful of another 9/11-style attack. When the Tripods mobilise and begin vaporising unsuspecting civilians, Ray runs for his life.

It’s at this point that Ray’s paternal instincts kick in. Despite being visibly shellshocked by the terror he has just witnessed, he calmly instructs his kids to pack their bags, no questions asked. But a dismayed Robbie demands to know what’s going on: “What is it? Is it terrorists?” It’s a perfectly innocent but telling question. Crucially, though, despite repeatedly evoking the painful collective memory of the Twin Towers – in one scene Ray trudges solemnly past a building that’s plastered with missing person posters; in another he covers Rachel’s eyes as they navigate the still-smoking wreckage of a passenger jet – the film doesn’t feed the climate of xenophobic paranoia that prevailed at the time (and which has more recently reared its ugly head again). One available reading of War of the Worlds is that it is an anti-war film, but its message is much more nuanced than that.

Later, when it’s revealed that the Tripods have been laying dormant beneath our feet all along (a plot point alluded to by the spoilerific tagline ‘They’re already here’), the implication is that the most imminent threat to Western civilisation is often a lot closer to home than we’re willing to accept. Not having the aliens beam down in massive spaceships is a genius move on the part of Spielberg and screenwriter David Koepp because it forces us to question the protocols and systems that have been put in place to protect us.

On top of this, War of the Worlds exposes the inherent fallibility of military intervention – as in Wells’ source novel, the aliens are eventually defeated not by manmade weapons, but a wholly organic one. The deus ex machina twist ending may seem overly convenient, even by Hollywood’s standards, but in truth nature’s judgement is often just as swift and devastating.

For a film that features so much chaos and destruction, War of the Worlds is remarkably composed and even optimistic in its outlook. It could so easily have been a barbed critique of the Bush administration, yet there’s no underlying liberal ideology, no hint of the quasi-political grandstanding that has become so prevalent in contemporary blockbuster cinema.

Instead, Spielberg presents us with an idealised vision of humanity in which ordinary citizens set aside their differences, bridging both literal and metaphorical boundaries, to defeat a common enemy. Still, for all that War of the Worlds captures the 21st century mood in microcosm, its real power lies in its personal, ground-level perspective on a global disaster. Its primary concern is not government or religion or war but the individual actions of a father desperately trying to reconnect with his kids.

In The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology, rock-star philosopher and culture commentator Slavoj Žižek, while analysing James Cameron’s Titanic, argues that had Jack and Rose survived, the misery of everyday life would inevitably have destroyed their love. When the iceberg hits the ship, the true catastrophe – their proposed new life together in New York – is prevented; only in death is the romantic fantasy of their brief fling kept alive. Put in these oblique cause and effect terms, the alien armageddon in War of the Worlds provisionally puts an end to an even greater crisis: the gradual erosion of the American family.

What do you think is the greatest blockbuster of the 21st century? Have your say @LWLies

Published 13 Jul 2016

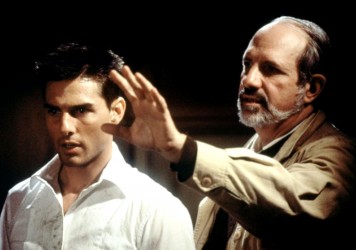

Twenty years ago Brian De Palma and Tom Cruise ushered in a new blockbuster era.

This tricksy, time-looping caper acts as a telling metaphor for the repeated resurgence of its leading man, Tom Cruise.

We take stock of the (almost) complete oeuvre of one of modern cinema’s true masters.