While Scream is generally considered to be director Wes Craven’s meta-masterpiece, his 1994 film New Nightmare poses even deeper questions relating to our collective lust for horror. The seventh instalment in the Nightmare on Elm Street franchise sees Craven return to a character he no longer recognised. Over the course of the 1980s, endless cheap sequels, a television show, cuddly toys and, most bizarrely, a phone hotline where Freddy Krueger could speak to your children before bed, had turned this once terrifying character into a laughable parody of itself.

Craven saw an opportunity to reclaim his creation and New Nightmare is purposefully designed to be viewed separately from the rest of the series. It portrays Freddy as having outgrown his own mythology – he invades the real world to haunt the cast and crew responsible for the original film. At one point, Heather Langenkamp, the actress who played Nancy Thompson, tells a nurse caring for her son – who is being tormented by the ‘fictional’ character, “Every child knows about Freddy, he’s like Santa Claus or King Kong!”

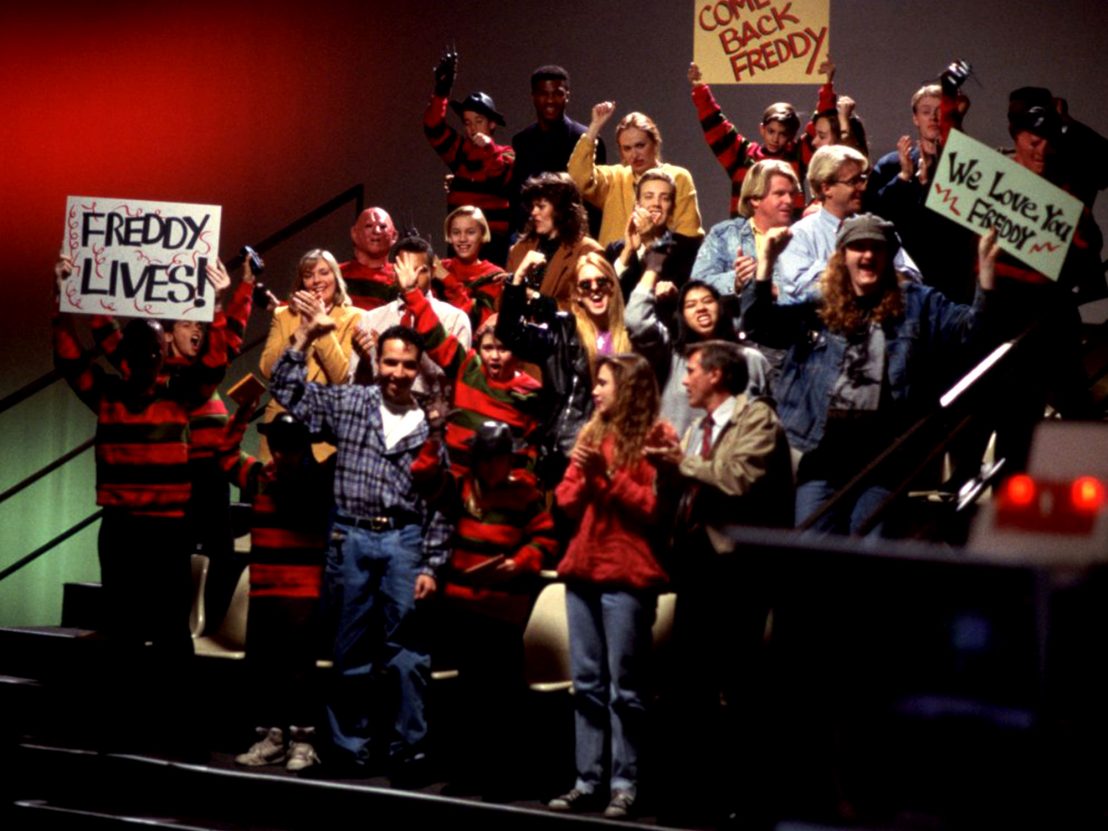

In one of the film’s strangest scenes, Langenkamp is interviewed on a TV chat show. To her surprise, actor Robert Englund is brought out in full Freddy attire, waving his menacing claws to an audience full of adoring children who are all dressed in his famous striped jumper and waving signs declaring, ‘We love you Freddy!’ alongside their parents. He even high fives one small child wearing a Freddy mask. The scene is particularly disturbing when you consider the character has always been a paedophile, someone who preys on young children and is burned alive by vengeful parents in the first film.

According to BFI’s cult film programmer, Michael Blyth, the chat show scene was a suggestion from Craven of what lay ahead. “It’s a warning about parental responsibility but also how the media is getting darker and darker,” he tells LWLies, “and how that is fundamentally changing audiences. He’s asking audiences to take a step back and look at this monster we’ve all created. Freddie was never intended by Craven to be a joke or hero, yet here we are.”

The underlying themes of New Nightmare are nothing new, according to film historian Paul Duncan. “Historically, we’ve always been the audience in the crowd that is cheering Freddy on,” he explains. “From Guy Fawkes to Frankenstein, society loves to glamourise its biggest monsters. Horror movies help us face our fears so that we can then digest them and turn them into something meaningless. By making it into a joke, we become less scared.”

It’s clear that Craven’s New Nightmare is first and foremost parodying the increasing commercialisation of horror as a genre, but it also works as a social commentary about the new media age. When the film was released, the nascent internet was developing at an express rate. Through the chat show audience, Craven foresees how something like the World Wide Web would whip audiences into a frenzy and almost commodify murder in even more disturbing ways.

Duncan agrees: “Craven was very interested in the media and how it takes hold of something and distorts it through commercialism. He’s warning us that the media will commercialise the darkest actions possible and that even a paedophile being cheered on by kids will one day not seem too ridiculous a concept. The media makes money from information and then sells it to audiences, no matter how disturbing it is.”

In a chilling late scene, having stopped Freddy from terrorising her son and defeating him in a dream world, Langenkamp wakes up to find a copy of the film’s events in a screenplay at the foot of the bed. Inside it is a note from Craven, thanking her for defeating Freddy and imprisoning the character to the fictitious world, once and for all. The scene appears to be a plea to audiences to prevent horror from being commercialised to the point of losing all meaning. You sense even Craven would have smiled sarcastically when Freddy was dragged back by Hollywood to fight Jason Voorhees just eight years later.

Published 17 Jan 2017

By Adam White

Wes Craven’s seminal 1996 film occupies a uniquely female space.

Movies have always reflected social attitudes and trends – and that could prove especially vital over the next four years.

The sudden passing of the horror maestro reminds us that the fear he produced transcended the screen.