The B-sides of a filmmaker’s body of work are often the most interesting; freed a little from what might typically characterise their storytelling. David Lynch’s The Straight Story is one such film. Released by Walt Disney Studios, the company’s name front and centre, the film is an ode to the pleasures of slow storytelling.

The Straight Story dramatises an event that occurred in 1994 when septuagenarian Alvin Straight (portrayed by Richard Farnsworth, who had once worked as a stuntman) drove about 250 miles from his home to visit his ailing brother. Alvin did not own a car and so made the journey by tractor.

It is wildly different to David Lynch’s previous road movie, Wild at Heart, yet has moments which similarly capture a sense of reality falling out of kilter very quickly: notice how neatly constructed the scene is in The Straight Story when Alvin encounters a driver who has, once again, had a roadkill moment.

Lynch’s producer, Mary Sweeny, read the screenplay by John E Roach that would became The Straight Story and was confident that Lynch would recognise the potential in it. When the movie was initially released in 1999, Sweeny, an interview with The Los Angeles Times, made a useful point about the film apparently being an anomaly in Lynch’s filmography, commenting that “dysfunction isn’t the only thing out there. He is pigeonholed as the master of weird, but is much more.”

This is a film about moving slowly and gently in a hard and fast world and, as others have observed, in this respect it’s akin to the films of Yasujirō Ozu. Like many of Ozu’s movies, The Straight Story quietly charts the pains of time’s passing and what the idea of a family means in both its potential for joy and for sorrow. The film’s moods shift easily from melancholy to glimpses of fleeting contentment in very ordinary situations and Alvin’s evident gladness at being alone in the American landscape.

In classic American road trip fashion, Alvin has broken free of the confines of the routine world as he passes through rural America. The images of fields, of highways and gently rising and falling ground suggests something of the ways in which the tradition of American painting has informed the tradition of American moviemaking. Lynch is a painter by training and The Straight Story is one of his most evocative and immersive canvases.

Here, the everyday is where the epiphanies roll in and out of view and one of the most affecting of these centres around Alvin’s encounter with a young woman who has fled home to avoid the family fallout around her pregnancy. After initially riding past her as she stands on the roadside the sequence then dissolves to sunset and a silhouette of ground against the sunset sky. Another shot shows Alvin sitting on a garden chair by a campfire he has made. Out of the darkness emerges the woman saying that she couldn’t get a ride. “Are you hungry?” Alvin asks, and in the solace of the campfire he and the young woman tentatively converse.

No music underscores the scene and it’s not too much of a leap to imagine that it could have been deployed. Alvin explains, “I’m heading to see my brother, Lyle.” While the conversation is a little faltering there’s a warmth to it and the pause and silences feel true to life. Alvin offers the young woman a blanket from the trailer and there is another prolonged silence before he adds, “My family hates me.” Alvin endeavours to provide some comfort as she explains her situation and he talks about his daughter Rose, ruefully relating something of her earlier life.

As he does the scene dissolves, taking us from the campfire and to a shot of a curtain gently lifting on a breeze at a window as the camera moves slowly around the room before the image dissolves again to show Rose sitting alone looking out of a window in which we see her face reflected. Now, we hear Angelo Badalamenti’s musical score at work and it enriches the scene. Alvin’s recollection ends and the scene returns us back to the campfire. In an attempt to break the melancholy mood, Alvin recalls a game he used to play with his children and in doing so the entire heartbeat of the film is at its loudest.

In 1999 a good friend of mine – a lifelong Lynch enthusiast – went to see The Straight Story as soon as it was released in the UK. Later, he told me how it moved him to tears. It’s one of those films that seems to resonate more the older you get. It’s a film about love and, to quote Blanche DuBois, the kindness of strangers.

The Straight Story marks a passage of time and the regrets and happiness that inevitably accumulate along the way. But, where it could have done all this with some quiet sound and fury, Lynch eschews it. Instead, like Alvin, his film sets out on its mission in its own unassuming way and; inviting as those campfire flames around which so many stories have been told.

Published 15 Oct 2019

By Adam Nayman

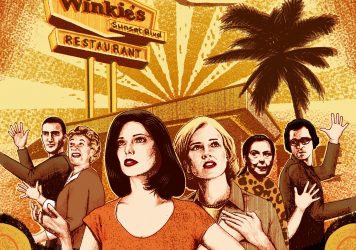

Is David Lynch’s warped Tinseltown satire from 2001 a contemporary riff on one of Hollywood’s classic-era staples?

Exploring the suggestive imagery and symbolic language in the director’s 1986 cult favourite.

By Greg Evans

If you recognise this scene, you’ll already know what’s coming...