Words

Jack Godwin, Gabriela Helfet, David Jenkins, Elena Lazic, Manuela Lazic, Adam Woodward, John Wadsworth

Illustration

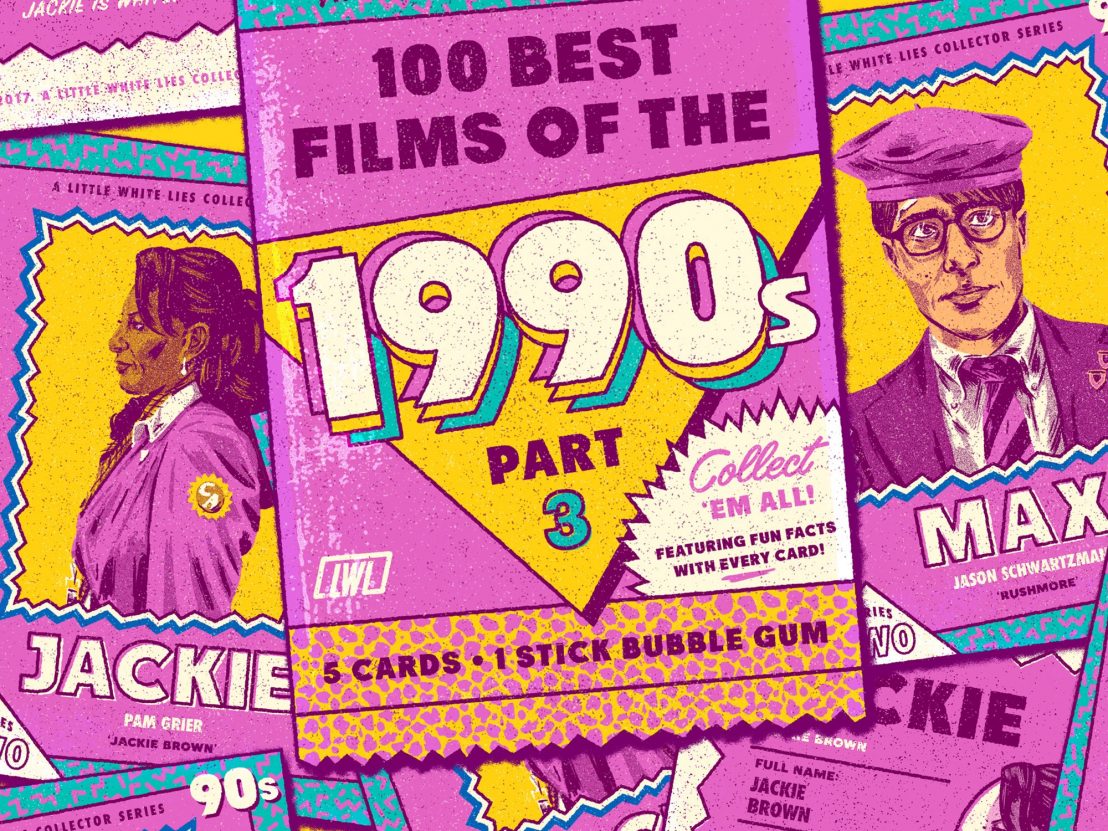

Martin Scorsese, Claire Denis and Terrence Malick break into the Top 50 of our ’90s countdown.

After you’ve read through this part of our countdown of the best films of the 1990s, check out numbers 100-76, 75-51, and 25-1.

They said that William S Burroughs wrote books that could not be transposed into other media, but that may be the very reason that David Cronenberg took on the challenge. This feature-length drug chimera sees Peter Weller’s lowly bug exterminator take a trip to the Interzone where he assumes the identity of a private detective in a space dominated by insectoid typewriters and sad-eyed Mugwumps. The film follows thrilling and intuitive narrative paths while embracing surreal imagery and plunging us into obscure, subjective dream states, and it is a supremely bold follow-up to the relatively crowd-pleasing likes of The Fly and Dead Ringers. Though drug movies tend to skew towards the comic and the absurd, this one actually stands as one of Cronenberg’s most strangely melancholy movies. David Jenkins

The name Ross McElwee is not that well known, and that’s because his films have seldom played in proper cinema rotation. But while they are certainly made for a small, discerning crowd who are open to the wry philosophical and cinephilic musings of a true southern gentlemen, it doesn’t mean they are not some of the great documentaries of the modern era. Time Indefinite is a devastatingly personal account of a filmmaker attempting to come to terms with his own mortality. He is enthralled by the prospect of bringing up his young son, but also has to deal with other personal tragedies that arrive from the other branches of the family tree. With a skeleton crew, McElwee ushers in his personal life as the film’s subject matter, but does so in a way which is never egregious or narcissistic. Quite the opposite: his self-deprecating wit and wisdom is a thick salve for the soul. DJ

The opening credits sequence of the Coens’ gangster-noir runaround, Miller’s Crossing, sees a hat float off through a forest clearing, an unchased McGuffin dreamt up by an unchaste mobster. Tom Reagan (Gabriel Byrne) loathes losing his headwear and his dignity, but he struggles to hold on to either for long. Caught up in a convoluted web of lovers and murder, he relies on his hard-boiled survival skills – manipulation and dirty tricks – and achieves mixed results. In typical Coen-brothers fashion, mistakes and misinformation abound. In such moments of confusion, we recall Tom’s fluttering fedora. It seems to promise answers to his many questions but, blowing in the wind, its own meaning proves just as elusive. John Wadsworth

It’s our firm belief that true greatness cannot be measured in shiny trinkets. As far as movies are concerned, awards are essentially arbitrary and certainly not an accurate indicator of quality. That said, it really is criminal that Denzel Washington didn’t receive every major acting gong going for his towering lead turn in Spike Lee’s biopic of the titular black activist. Malcolm X was a complex man and a controversial public figure whose life captured in microcosm America’s long struggle with race and class – Washington embodies this as perhaps no other actor could. Adam Woodward

The French filmmaker Arnaud Desplechin does good chat. He has the natural ability to turn banal conversations into enthralling spectacles, and that’s down to his incredible ability as a writer of dialogue (mellifluous, literate, but never too much so) added to the fact that he works with awesome actors. The stars of this winding autobiographical epic from 1996 include Mathieu Amalric as the charming, changeable Paul Dedalus (Desplechin’s screen alter-ego), and the always-scintillating Emmanuelle Devos as his more cultivated on-off lover, Esther. There’s no handy three-act structure or cosy resolution – My Sex Life… is a hardcore, outspoken slice of life, and it thankfully includes lots of the really juicy stuff. DJ

As the old internet meme goes, this one is back in the news. Not because of Warren Beatty’s unfortunate foul-up at the 2017 Academy Award ceremony, but due to the fact that this outspoken and provocative 1998 film is about a suicidal Republican senator who decides that he’s going to tell the unvarnished truth. And what’s more, he’s going to spit it out in hip-hop couplets. And the people are going to love him for it. As star, director and co-writer (along with Jeremy Pikser), Beatty is some twenty years ahead of the curve in his all-guns-blazing desecration of corrupt politicians, toadying lobbyists, and a system built on the crooked foundations of greed, racism and lies, lies and more dirty lies. DJ

Badass doesn’t even begin to describe John Woo’s gloriously overblown pistol opera, in which a self-styled “supercop” named Tequila (Chow Yun-fat) gives himself the considerable task of taking down the local arms cartel run by peach-suited bastard, Johnny Wong (Anthony Chau-Sang Wong). Ammo is no object as he leaps and dives through tea-shops and dockside factories whacking out an almost endless succession of gurning goons and minions. He tries out all manner of firearms, and eventually settles on a giant pump-action shotgun, with explosive results. This is an exhilarating dirty bomb from peak-era Woo – his sole aim as a director is to make the next action set-piece more insane, more violent, and more unforgettable than the last. And, dammit, he succeeds with fiery gusto. DJ

Is it possible to be killed by cinema? Not just emotionally, but physically too? Lee Kang-sheng – actor and muse of director Tsai Ming-liang – plays a young man who unwittingly agrees to become an extra on a film shoot, possibly to impress a woman. He is asked to pretend to be a corpse floating in Taiwan’s Tamsui river, and he just has to float in the polluted water for a few seconds. The film then plays out like an lugubrious urban nightmare, as he develops an itch in his neck that he can’t quite scratch, and it drives him towards madness and beyond. And that’s before we’ve met his parents. Tsai is one of the progenitors of so-called “slow cinema”, and rather than that unhelpful tag pointing towards abject dreariness, it’s more that this master director allows you to (literally) drink in all the mysterious detail he delicately places on the screen. DJ

It’s a crying shame that the actor Danny Glover might end up being remembered as the cop sitting on a toilet that’s been wired to explode. In Charles Burnett’s haunting dissection of the modern black American family, To Sleep with Anger, he delivers a performance so subtle, so precisely calibrated and so utterly in tune with the tone of the material, that it should really go down as one for the ages. The film bares a light resemblance to Pier Paolo Pasolini’s classic Theorem, and sees a strange interloper (played by Glover) enter into a family and manage to tease out all the festering resentments and unfulfilled dreams. On the surface it’s a small, independent drama made via modest means by the pioneering Burnett, but it’s also the result of careful moviemaking craft that is powered by confrontational ideas and a sense of barely-concealed rage. DJ

The best biopics evade purely factual retellings of a life to create a more sensory experience of their subject, taking them out of school books and into the realm of everyday reality. Maurice Pialat’s penultimate film follows this principle to an almost painful degree. The last few days of the renowned Dutch painter’s life are told practically without any dialogue, the sounds of the French countryside dominating the soundtrack. The sense of place is overwhelming, and Van Gogh himself – wonderfully played by French pop singer Jacques Dutronc – does not try to stand out from it. On the contrary, the man seems engaged in an intimate relationship with nature, which the world is privy to via his vivid paintings. Pialat’s camera captures Van Gogh and his art in unvarnished shots that only emphasise their strength and radiance. This conflict between the rhythm of everyday life and that of history in the making permeates every frame, and it is beautiful. Elena Lazic

This tremendous and unheralded domestic drama from Australian director Rowan Woods is a film in which a sense of hair-trigger violence is floated into its every, beautifully-judged frame. A young, bog brush-haired David Wenham stars as thousand-yard, ex-con berserker Brett Sprague who is released from chokey on parole and heads directly back to the family nest. Everyone prays for a new, becalmed and tolerant Brett, but it becomes swiftly apparent that his time inside has cultivated rather than curtailed his festering resentments. Toni Collette turns in a spiky early performance as his jilted lover, and the film itself becomes an exercise in watching-through-your-fingers as you wait just to see how it all goes wrong, and how badly. And it’s one of those films that, when the credits roll up the screen, you’ll have to choke your heart back into place. DJ

Krzysztof Kieslowski made a career of challenging the very worst of human behaviour with unwavering compassion and understanding. It seems fitting that his last ever film, and the final chapter of his iconic Three Colours trilogy, explores one of the most painful of human traits: the capacity for deceit and betrayal. Through the character of young, idealistic model Valentine (Irene Jacob) and the disillusioned judge Joseph Kern (Jean-Louis Trintignant), the Polish master takes us on an emotional journey where appearances are treacherous and coincidences go unnoticed. Culminating in a moment of transcendent optimism and grace, this poetic masterpiece on forgiveness somehow lost the Palme d’Or in Cannes to another ensemble drama of sorts, Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction. EL

We, like you, utterly despise the term “game-changer”, and do everything in our meagre power to avoid using it, particularly when discussing the joys of the nickelodeon. However, the term seems necessary when referring to Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez’s shaky cam faux-doc – a bolt from the blue which altered the terrain for genre cinema and made an ungodly sum of money at the box office. Building a mythology around the film before its release, the makers worked hard to build conditions that would make potential viewers believe that everything they’re seeing is real. Luckily, they discovered a clutch of feisty young actors who were in on the game, and so delivered a film in which innocent folkloric superstition and guerilla student filmmaking join together in an pulse-quickening woodland nightmare. DJ

Al Pacino’s big, kind eyes say more about Carlito than his explanatory voiceover: the ex-conman, fresh out of prison, wants to believe again in the beauty of life. Director Brian de Palma employs his trademark voluptuous filmmaking to translate the hopeful passion that Carlito manages to bring back to his girlfriend, making this his most tender and romantic film. Yet the director’s pessimistic view of humanity hasn’t left him as Carlito can’t simply forget the code of the streets, nor can he rely on the law to protect him, corrupted as it is by selfish greed and rampant distrust. Even the most genuine and overwhelming love can’t survive when redemption remains but a dashed dream. Manuela Lazic

From things that are as intangible as mending heartache to those as real as a ceramic pot steaming with hot ramen, the Japanese are at their most awe-inspiring when focused on a single entity in a nuanced way. This film finds maestro Hirokazu Koreeda applying that attention to detail to the afterlife: when you die you can choose one memory from your existence to bring to the other side. Ethereal, moving, and exquisitely beautiful in its simplicity – like all great Koreeda films – it is a subtle exploration of the palimpsest that memories leave on your soul. Gabriela Helfet

Film lovers the world over waited 20 long years for Terrence Malick’s follow-up to his ravishing big-sky opus, Days of Heaven. And boy, the big man didn’t disappoint. Perhaps the most philosophical movie ever released by a major film studio, The Thin Red Line is less a war film and more a profound existential odyssey – not that the director told his ensemble cast as much: “It was physical, it was dirty – no shower in a week in the bush, digging our own trenches and staying up half the night on lookout, it was the real thing,” actor Dash Mihok has recalled of the experience. A film with grit under its fingernails and poetry in its heart. AW

The leap between Portuguese director Pedro Costa’s 1989 debut feature, Blood, and his 1997 follow-up, Bones, is a giant one, but not in the most obvious direction. He displayed a dazzling technical bravura in that impassioned opening missive, yet everything in this follow-up is tamped down to the point of poetic innocuousness. He captures the young derelicts of the grotty suburb of Lisbon called Fontainhas, and observes as drug habits and a general lack of opportunity drag them down to rock bottom. The manner in which he films his actors displays the patient quality of a master portrait painter. Yet these are not conventionally beautiful depictions of human frailty. The images he produces are haunting and indelible, as if his camera looks straight through the skin and into the soul. DJ

Draconian censorship laws in Iran push filmmakers to look beyond point-blank statement-making to matters more profound and poetic. In this strange film, veteran director Mohsen Makhmalbaf opts to restage an event for which he was sent to prison as a youth – the stabbing of a policeman during a protest. A Moment of Innocence presents an impulsive, life-altering act, but questions the power of cinema to ever be able to amply recreate the nuance and feelings that existed in a bygone past. It sounds deadly serious, but as with much of the director’s work, proceedings are shot through with levity and humour. The policeman on the business end of Makhmalbaf’s knife actually became an actor since the incident and, bizarrely, is discovered when auditioning for one of the director’s films. DJ

Long, heavily improvised rehearsals were integral to the process of making Naked, a collaborative exercise that ensured that the characters and interactions that make up Mike Leigh’s arresting drama remained unadorned in their emotional honesty. At its centre is David Thewlis’ brutally cynical gadabout, Johnny, an intellectual on the run from the past committed to convincing others of the futility and malevolence of the human race. Johnny is so steeped in hatred for himself, the world, and the people who inhabit it, that it spreads to every corner of the film. His odyssey through the hellish landscape of the city connects him with other lost souls, desperately seeking to survive without families, jobs, love or hope. Johnny’s motor-mouthed nihilistic rants have the eloquence of pulpit sermons, but are grounded by the authenticity of Thewlis’ masterful performance. Jack Godwin

There’s a significant shadow cast over modern cinema by Martin Scorsese’s mob epic, a film that is endlessly re-watchable even as we follow Henry Hill’s (Ray Liotta) increasingly perilous descent into criminality. Despite arriving 30 years into the director’s career, it is the central reference point for Scorsese’s distinct filmmaking style. The director builds Henry’s life through small interactions with a richly detailed cast and extraordinary dialogue often developed from improvisations. The long tracking shot through the Copacabana club demonstrates the allure that this life holds for Henry, the scale of which is communicated entirely through Scorsese’s formidable camerawork. There’s no condemnation or glorification of Henry’s criminal lifestyle, but razor-sharp awareness that allows us to enjoy his exploits again and again. JG

If films only ever focussed on likeable characters, they’d be boring. Yet not every director can make a flawed person worth watching for hours. Whit Stillman’s debut feature consists entirely of obnoxious people, centring as it does on a group of preppy New Yorkers during gala debutante season: not even the not-so-elite Tom Townsend (Edward Clements) or the gentle Audrey (Carolyn Farina) remain pristine. Yet by highlighting the existential questions constantly on the minds of these beautiful people, Stillman avoids sentimentalism to instead find touching humour in their at once elevated yet somewhat petty discussions. Eschewing melodramatic and upping the witticism quotient, the film sees relationships gently evolve until these privileged youngsters suddenly realise their attachment to each other – and the audience to them. ML

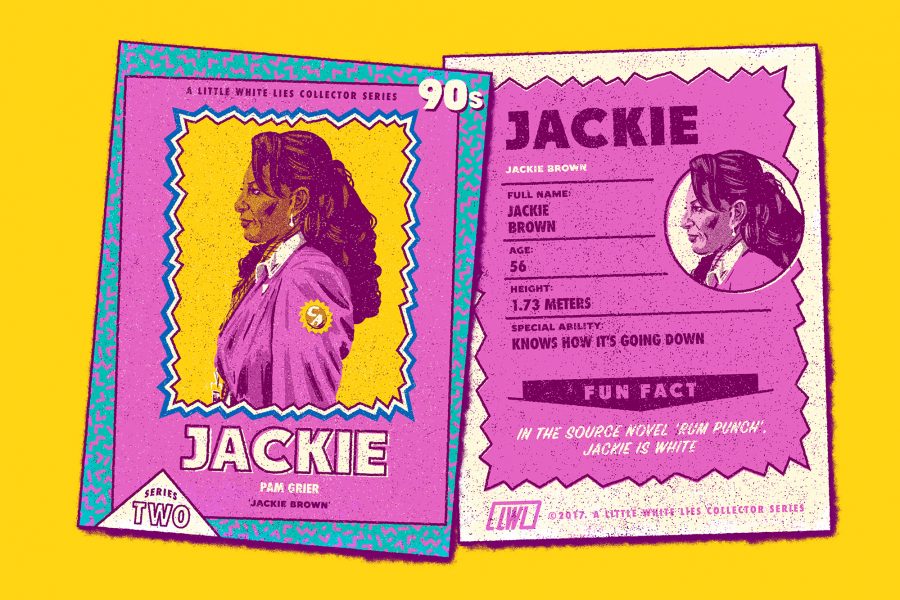

Jackie Brown is probably Tarantino’s least bombastic film, but also, more interestingly, his most romantic. Jackie (Pam Grier) belongs to the Blaxploitation tradition, but the director updates the physical prowess and Manichaeism typical of these heroines into a more realistic shell of endurance and wit. Besides smuggling arms money for her boss Ordell (Samuel L Jackson), middle-aged Jackie isn’t looking for trouble. But when complications occur, it’s to each their own, until she finds in bail bondsman Max Cherry (Robert Forster) an unexpected partner in crime, and maybe more. Crosscutting between the disturbed people around her, Tarantino creates a medley of opposing atmospheres through which he presents the title character as a complex woman, at once strong and sensible, independent yet emotional. ML

A miniature treat from the ‘Tous les garçons et les filles de leur âge…’ TV series made for French television, as Claire Denis whisks heady magic from a wisp of a set-up. It’s 1965 and two girls living in the Parisian suburbs want to lose their virginity, and so saunter off to a nearby US army base looking for some action. What they find is Vincent Gallo’s kindly Captain Vito Brown who, shall we say, takes them on a unique journey. More than a conventional drama, the film is an example of how Denis is able to formulate an atmosphere, and here it’s propped up by a succession of ’60s radio alt-rock hits from the likes of The Animals, The Troggs and Nico. A small but perfectly formed gem. DJ

There’s hard, there’s double-hard, and then there’s “Beat” Takeshi Kitano. When talking about the “serious” film work of this Japanese stand-up and TV celebrity, conversations begin with his matter-of-fact 1989 debut, Violent Cop, and end with 2003’s sword-swishing crowd pleaser, Zatoichi. Smack dab in the middle of that period is his masterpiece, Hana Bi, a film whose story makes a habit of turning on a dime from hushed, Zen-like contemplation to brain-splattering violence. It’s a melodrama of sorts in which a Christ-like cop (played by a perpetually poker-faced Kitano) resorts to crime as a way to care for his old injured cop buddy and his dying wife. Every shot is calculated to perfection, with each edit slicing through the action with almost surgical precision. And Joe Hisaishi’s swooning score is the cherry on the top. DJ

“How long has it been since you fired a gun at a man, Will? Nine, 10 years?” “Eleven.” Clint Eastwood’s revisionist western is set in a world in which things are not only bad, they are also sad, and more than a little pathetic. William Munny (Eastwood), a retired gunslinger ridden with guilt for his violent past, retrieves his gun for one last job and immediately finds himself faced the same egomaniacal and hostile machismo he had hoped to leave behind. The spectacular deaths and shootouts that myths are made of recover here their full gruesomeness and disheartening sense of waste. Eastwood and the flawless supporting cast – Gene Hackman is a highlight – deliver some of the most rich and nuanced dialogue of the decade, every line heavy with deeply miserable implications. It’s a hell of a thing, killing a man. EL

Now read numbers 25-1Published 15 Mar 2017

By Tom Graham

Twenty five years on David Cronenberg’s adaptation of William Burroughs’ classic novel remains a bold and transgressive vision.

A comprehensive guide to the directing credits of this great American auteur, from Mean Streets to The King of Comedy to Killers of the Flower Moon.

By Taylor Burns

Terrence Malick’s 1999 epic is a stunning meditation on the natural world and our relationship to it.