In 1998, Chicago Reader critic Jonathan Rosenbaum compared two new releases by two filmmakers of roughly the same generation: Steven Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan and Joe Dante’s Small Soldiers. One is a prestigious and patriotic war picture that took home five Oscars, the other is a silly movie for kids. Though Spielberg’s film is generally considered to be the superior and more serious of the two, Rosenbaum preferred the latter, praising Dante’s criticism of “not just culture and violence but also everyday cultural violence.”

Both films are now 20 years old, but history sided against Rosenbaum: Saving Private Ryan is considered one of the great modern war epics while Small Soldiers has been largely forgotten, except perhaps as an object of nostalgia. But perhaps the argument made two decades ago is worthy of revisiting. What if an often-overlooked children’s movie is actually one of the great American anti-war films?

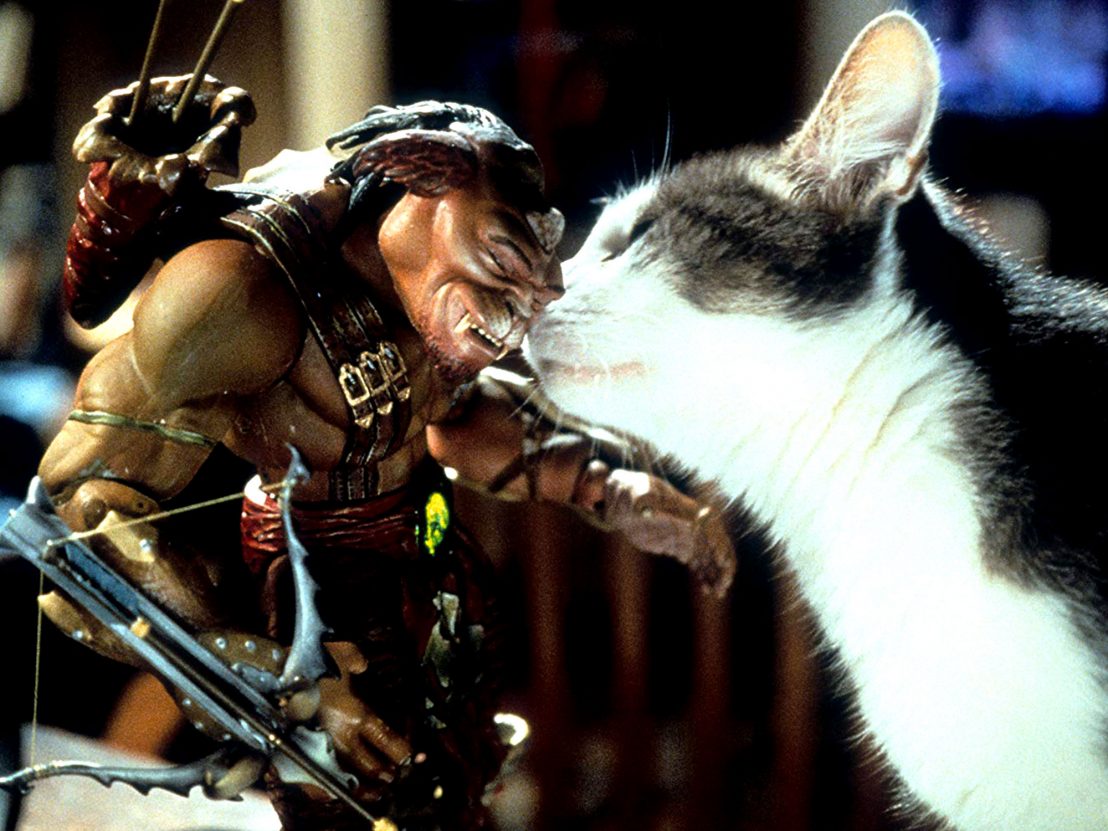

The hero of Dante’s film is Alan Abernathy (Gregory Smith), a troubled teen who accidentally acquires a set of state-of-the-art playthings developed by Heartland Toy Company, a new division of defence contractor GloboTech. Heartland’s new toy lines, the Gorgonites and their sworn enemies the Commando Elite, have been inadvertently installed with microchips intended for ballistic missiles and programmed to wage very real war against each other. This conflict explodes in the backyard of Alan’s home, where toys and humans alike are tortured and traumatised. As the tagline for the Commando Elite prophetically reads, “Everything else is just a toy.”

Small Soldiers is two things at once; as Roger Ebert noted in his review, it’s a “family picture on the outside and a mean, violent action picture on the inside.” Dante himself acknowledged this tension in a 2008 interview, claiming “[he] was told to make an edgy picture for teenagers, but when the sponsor tie-ins came in the new mandate was to soften it up as a kiddie movie. Too late, as it turned out, and there are elements of both approaches in there.”

Though many critics at the time considered Dante’s fusion of family fun and horror violence a failure, this synthesis is actually to the movie’s benefit: Small Soldiers is about how violence is sold to us. As the defensive company executive played by Denis Leary remarks, “Don’t call it violence. Call it action. Kids love action.” The most effective way to sell conflict to the voting public is to make it attractive to children. Then parents have to buy it.

A number of critics, including both Ebert and Rosenbaum, compared Small Soldiers to the earlier Toy Story. A more useful parallel might be Jurassic Park, both in its narrative about a science experiment gone wild and the tension that exists between its onscreen politics and off-screen merchandising. Jurassic Park might have criticised those who would exploit nature for profit, but it attempted to do the very same thing through its voracious marketing campaign, which stamped the franchise’s tyrannosaurus logo on everything from fast food to lunchboxes, inside and outside the movie.

Small Soldiers, the sixth film produced by Spielberg’s DreamWorks Pictures, attempted to pitch a similar multimedia tentpole. The VHS for Small Soldiers included a promo for the Small Soldiers “Total Experience”, advertising a soundtrack album, video game, and action toys with names like “Ground Assault Vehicle” and “Buzzsaw Tank”, all set to the ironic tune of Edwin Starr’s ‘War’. Major Chip Hazzard (voice by Tommy Lee Jones), the film’s primary plastic antagonist, is more prominently emphasised in artwork and advertising copy than the gentle Gorgonites.

This might seem to contradict the point Dante makes about how “action” toys normalise our culture’s thirst for warfare, but it only emphasises his message further. Denis Leary’s defence executive uses the toy division of his company to create a need for the weapons wing of his multinational corporation. Images of strong soldiers and heavy artillery are pushed on children and their parents in order to reaffirm America’s original pastime: armed conflict. Seeing that Small Soldiers exists inside the same culture Dante seeks to criticise, it only makes sense that the movie’s advertising campaign would mimic its diegetic equivalent, advertising aggression over peaceful understanding.

Small Soldiers goes beyond Jurassic Park in its diegetic critique too: the film’s real villain isn’t a misunderstand grandpa with an overambitious dream like John Hammond, but the entire military-industrial complex. In a world where Amazon works with the Pentagon and Disney wants to own every pop culture icon it can, Dante’s critique of multinational monopolisation resonates even more today than it did in 1998.

While Small Soldiers may not be included in the conversation about the great war movies, maybe it’s time we change that conversation. Small Soldiers criticises the American military apparatus by moving the frontlines from historical battlefields to the suburban home, focusing on the cultural normalisation of war instead of war itself. Just as he did in Gremlins, Dante reveals the combat zone hidden inside the American household. Potential weapons, from garbage disposals to chainsaws to Barbie dolls, lurk in every corner. Dad’s tool chest can become a torture chamber. A Spice Girls CD can be an instrument of psychological warfare. Every plowshare is a sword in disguise.

Small Soldiers avoids making war look glamorous by making it look unfamiliar, revealing the horrors hidden in our own homes. So maybe it’s time we took this particular kids’ movie seriously. Everything else is, after all, just a toy.

Published 21 Jul 2018

By Greg Evans

Between them Batman & Robin, Spawn and Steel pointed the way forward for the genre.

In the wake of his untimely death, we remember James Horner’s vital contribution to this family classic.

By James Clarke

Does the director’s take on JM Barrie’s classic tale of arrested development deserve its reputation?