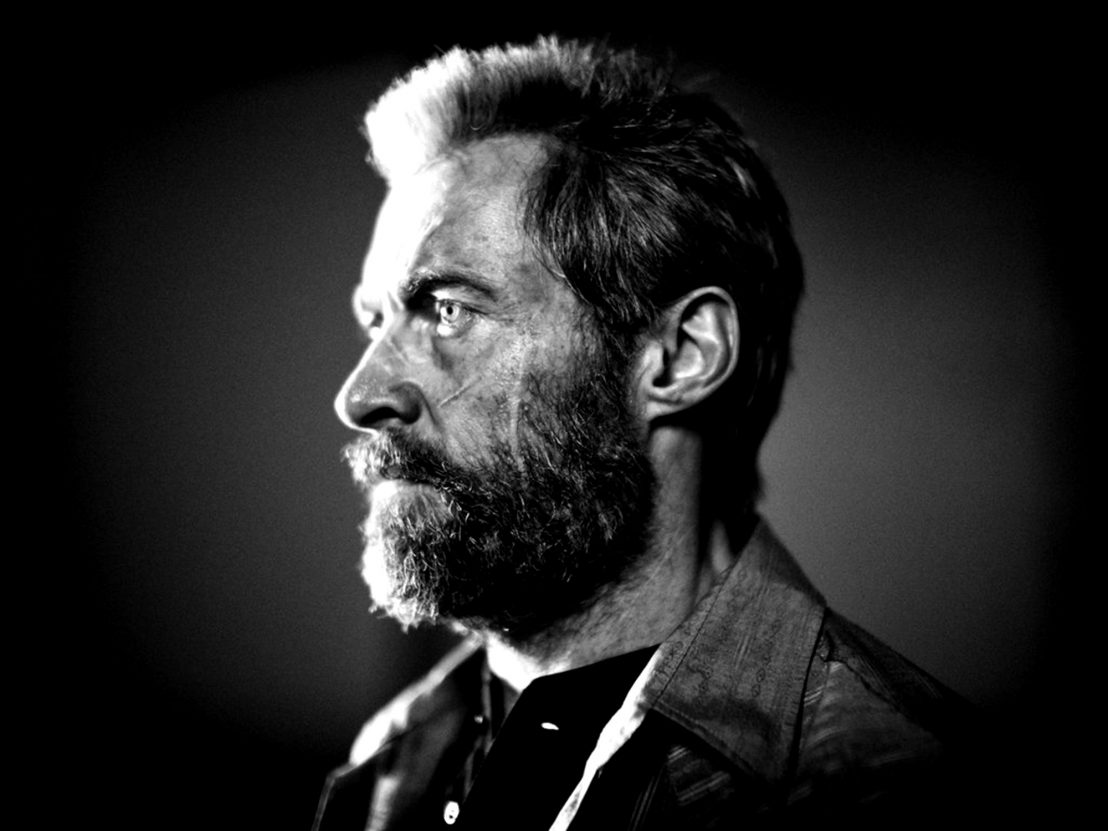

A fitting end to a incredible 17-year run, Logan, Hugh Jackman’s sensational curtain call as Wolverine, looks set to reinvigorate the X-Men film franchise and make a final, definitive statement on the actor’s most iconic role. In more ways than one, Logan marks the end of an era, the final word on a character that has been allowed to grow and develop on screen over the best part of two decades. Indeed, the mature, character-led approach that Logan takes is not only a major departure for the series, but a potential turning point for the comic-book movie genre as a whole.

With 2016’s damp squib, X-Men: Apocalypse, and outright stinkers like X-Men Origins: Wolverine, the series as a whole has suffered from a lack of consistency, but Logan shows there’s plenty of life left in the old mutant dog yet. One thing you can say about the X-Men films is they’ve always been willing to experiment, for better and for worse. Following Origins, for example, the ’60s-set soft reboot First Class sounded terrible on paper but remains a series highlight. And for all its low-brow larks, Deadpool broke new ground as an ultra-violent superhero film that mockingly breaks the fourth wall. Hell, even the otherwise risible The Last Stand killed off three of its main players, a trick we’ve yet to see the Marvel Cinematic Universe pull.

And now, James Mangold’s follow-up to his solid but standard-issue 2013 spin-off The Wolverine further subverts expectations. Patrick Stewart’s Professor X – the paternal centre of the series – is suffering from a degenerative brain condition that causes horrible psychic seizures, Logan’s adamantium skeleton is slowly killing him, and mutants are in worldwide decline. The happy future promised at the end of Days of Future Past is apparently all but forgotten amid a society on the brink of collapse, bringing into question whether the events of previous films ever happened.

The series’ sense of experimentation is something that the monolithic Marvel Cinematic Universe could certainly learn from. Guardians of the Galaxy and Ant-Man were pitched as risky propositions, but in truth they were the hardly the envelope pushers touted by Marvel’s acolytes. Although the studio’s risk-averse approach has resulted in a consistent level of quality, Marvel’s model is unlikely to produce something as authentically dramatic and gritty as Logan. Indeed, the film’s success as an emotionally-centred character study opens the door to future superhero films not beholden to the formula that has blighted Marvel’s middling efforts.

In terms of tonal and structural variety, no other series can touch the X-Men films – Logan is as different to Deadpool as Deadpool is to First Class. Compared to Marvel’s meticulous release schedule, however, Fox’s approach is more see-what-sticks; we still don’t know for sure what the next X-Men film will be. Continuity has never been much of a concern for the studio – it’s difficult enough finding two entries in the series whose plots don’t contradict each other, let alone making sense of all 10 of them.

Fans of the X-Men comics might baulk at these continuity gaps, but movies aren’t always logic puzzles with neat solutions. Good filmmaking requires emotional context, dramatic conflict, tension and catharsis. It’s not a case of simply slotting jigsaw pieces together. The X-Men films have long understood the functional messiness of storytelling, and Logan breaks the series’ loose rules in service of its own story. The film acknowledges this with its reference to the X-Men comics, a more elegant version of Deadpool’s arch meta-humour. More than just an easter egg, the comics in Logan represent a conscious unburdening of in-universe logic in favour of emotional and thematic integrity.

For years, commentators have heralded the death of comic-book adaptations. Even Steven Spielberg predicted in 2015 that superhero films would eventually go “the way of the western”. Of course, this ignores the fact that westerns are far from extinct – the so-called “post-western” era has produced some of the greatest examples of the genre, from revisionist masterpieces such as Unforgiven, to 2015’s haunting Slow West and 2016’s Hell or High Water. With its frequent hat-tips to classic psychological western Shane, Logan symbolically acknowledges the inevitable future decline of its own breed, while also pointing to a richer and more mature future for the genre.

Logan might be the best X-Men film to date, but much like 2008’s The Dark Knight, it also raises the bar in terms of quality and maturity in superhero cinema. Much has been made of Deadpool’s R-rating, which seemingly cleared the way for Logan’s bloody retribution and frequent F-bomb dropping. No doubt, Fox’s aversion to graphic violence and excessive cussing will have been allayed by Deadpool’s commercial success, but Logan isn’t made for sniggering adolescents – it earns its R-rating by employing a mature storytelling style.

It’s now up to Hollywood to learn from Logan. Not to merely ape its tone, but to realise that risk – real risk – can reap rewards at the box office, and that an entire generation which has grown up with comic-book adaptations is now ready for real drama and emotional complexity.

Published 28 Feb 2017

By Tom Bond

The prospect of Brie Larson as Captain Marvel is cause for celebration and concern.

By David Hughes

Like Superman during the Great Depression, today’s superheroes are in-sync with our complex political climate.

By Tom Bond

Brad Bird’s soaring 1999 animated feature taught us that true heroism is much more than quips and spandex.