While it has been showered with a great many (much deserved) compliments and labels, one word that could never be used to describe Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro is ‘conventional’. Utilising the genius of the late author James Baldwin, Peck explores race in America and the untimely deaths of Baldwin’s friends and contemporaries Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X via excerpts of his books ‘Remember This House’ and ‘The Devil Finds Work’.

Rather than construct a simply biopic of Baldwin, or a film about the racial climate in America during the 1960s, Peck skips between time periods, showing us civil rights marches one moment and Black Lives Matter demonstrations the next. It’s not the only unconventional element of the film – his choice of Samuel L Jackson as the film’s narrator, who delivers a performance that channels but never seeks to impersonate Baldwin is particularly inspiring. But one of the most delightfully unexpected moments of I Am Not Your Negro comes when Kendrick Lamar’s ‘The Blacker the Berry’ plays out over the film’s closing credits.

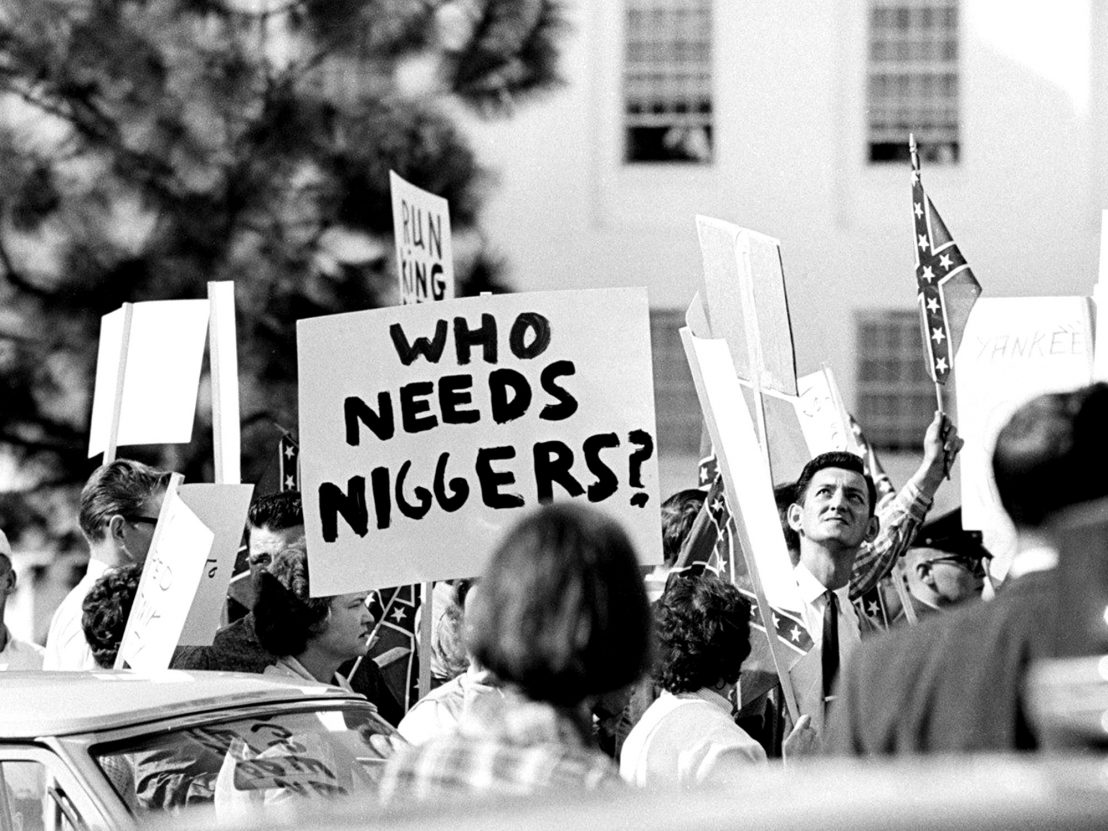

What is remarkable about Peck’s use of this song, setting aside the joy that one gets from imagining a 64-year-old man listening to contemporary hip-hop, is the way he uses it. Rather than playing the track from the top, Peck jumps straight from Baldwin’s closing remarks – “If I’m the nigger here, and you, the white people invented it, you’ve got to find out why. The future of the country depends on if they’re able to ask that question.” – into the song’s chorus.

What may seem like an easy or obvious choice – using a Kendrick Lamar song for the sake of using a Kendrick Lamar song – is actually an astute one. (And if Peck were indeed bending to populism, surely he would have gone for Lamar’s ‘Alright’, the adopted anthem of Black Lives Matter.) It’s a pointed choice, too – rather than leave the viewer ruminating on their thoughts while a piece of inoffensive music plays, Peck continues to run with one of the film’s recurring themes. ‘This is not over’, he is saying. ‘You’ve listened to Baldwin’s words about what happened then, and you will listen to what’s happening now.’ Accountability is a crucial part of I Am Not Your Negro, and Peck uses this aural motif to continue to hold his audience to account.

Not only is Peck’s choice of song radical in the way it is used, it also speaks directly to the means by which Peck, Lamar and Baldwin make their respective points about the “Black American experience” – through anger. The intense rage felt in ‘The Blacker the Berry’ is right there in Lamar’s lyrics: “You hate me, don’t you / You hate my people, your plan is to terminate my culture.” But there’s something specific about the type of anger that these three men share. They pull away from the irrational ‘angry black man’ stereotype that we’ve seen countless times before in film and television, because there’s no need to be irrational here.

No one has ever appeared cooler while dropping bombshells than Baldwin, cigarette in hand, on The Dick Cavett show. And Lamar is scathing and measured when he delivers the line: “I’m the biggest hypocrite of 2015 / Once I finish this witnesses will convey just what I mean.”

Marlon James writes of ‘The Blacker the Berry’ for the New York Times: “He has just realised that the only response to the stereotype of the angry black man is to get angrier.” The reasoning for this calm, collected anger? These men have the facts. The discourse around the subject of racism has changed thanks to the progression of technology, and you’d now be hard-pressed to find someone who hasn’t seen at least one video of police brutality in recent years. Lamar and Peck are simply laying out preexisting facts.

It’s clear that Peck isn’t using Lamar’s song for the sake of being down with the kids. He’s pointing to this contemporary cultural moment, with its blistering lyrics that could easily have been drawn from the pages of one of Baldwin’s novels, in order to highlight the similarities between the two. Lamar’s ire is an echo of Baldwin’s. The anger these men share is not based in a single moment or specific time period – as Baldwin says, it’s something that will continue until white America asks the question. Until then? Men like Baldwin and Lamar will continue to be angry, and men like Peck will continue to unite them.

Published 1 Apr 2016

By Matthew Eng

James Baldwin reclaims the spotlight in Raoul Peck’s magnificent film essay.

How a handful of filmmakers and a simple hashtag turned stories of African-American oppression into a national concern.

Stanley Nelson offers a broad survey of the militant political party.