Among the most striking images to emerge from the Grenfell Tower tragedy were those of Adele visiting the site. They show not a celebrity but an ordinary woman, tired and distraught, reaching out to help. Meanwhile, the stories of the victims’ lives suddenly become swathed in significance. Before political lines are drawn, tragedies such as this reveal concentrated moments of humanity when the impulse for compassion and the shock of loss transcend social position.

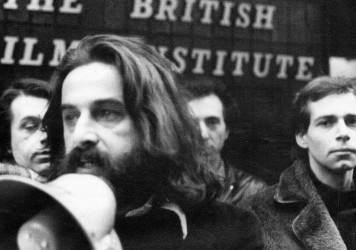

Humphrey Jennings, one of British cinema’s most influential if lesser-known directors (Lindsay Anderson went so far as to call him “the only real poet that British cinema has yet produced”), crafted his films out of such images. In a time where voices feel they are going unheard, his films probe scenes of British life for a sense of a unified consciousness, showing us ways of seeing – and hearing – a Britain divided.

Born in 1907, Jennings died prematurely in 1950 when he fell from a cliff while scouting for locations in Greece. His film career was brief but busy. He started out making documentaries with the General Post Office Film Unit while acting as the principal organiser of the 1936 Surrealism Exhibition in London (where Salvador Dalí lectured from inside a deep-sea diving suit). In 1937, influenced by the Surrealists’ attention to the everyday, Jennings set up Mass-Observation, where volunteer observers would anonymously record aspects of daily life, including ‘the anthropology of football pools’ and ‘the private lives of midwives’ (the archived results are still accessible at the University of Sussex).

Multi-faceted and generous in his interests and actions, Jennings was a proponent of social realism while simultaneously breathing poetry into a form as potentially dour as government sponsored documentary. Against the more staid productions of the time which sought to expose the harsh realities experienced by workers, Jennings’ more oblique and whimsical accounts reveal a vibrant and markedly self-sufficient community.

1939’s Spare Time looks at the leisure activities of workers in the coal, steel and cotton industries. In line with the surrealist use of montage, Jennings draws out new realities through contrast: darts, choirs and football are woven together with more peculiar moments, such as the Lancashire youth kazoo band, complete with their own Britannia held aloft.

World War Two, and more specifically the Blitz, was a period when Britain had to consider anew its own sense of self, a context that allowed Jennings’ films to come into their own. Commissioned by the British Government and intended to boost morale, his output in the early ’40s sought to understand and preserve ways of life directly under threat and reflected the ideals present within his form by creating a unity among previously disparate people.

Jennings’ only feature, 1943’s Fires Were Started, depicts a day and night in a volunteer fire department with remarkable subtlety. Just as these men and women found themselves in new roles protecting the city, Jennings allows them to become film actors by creating a space in which they can express their own characters and experience. Jennings draws out humanity through humour until, as the tension rises with the growing fire, all faces and voices are blackened out in a harrowing depiction of these volunteers’ nightly pursuit. The endeavour to protect the city and its inhabitants from physical elimination provides the ground to eradicate social distinctions, and a powerful empathy emanates from these unassuming protagonists, recalling the responses of today’s emergency services operating under increased financial pressures.

Jennings’ masterpiece, 1942’s Listen to Britain, has no voiceover and simply knits together scenes and sounds from a day in the life around Britain. Showcasing rural and urban communities, soldiers and civilians, propaganda filmmaking has never been so indirect or un-militaristic. Jennings creates a patchwork that invites the viewer to perceive continuities, whether it’s a cigarette behind the ear, the whistling of wind or the slow looks of thinking eyes. These details feel trivial until they are illuminated by crisis, by sharing the same warplane-filled skies whose sinister low drones sound throughout.

In the film’s standout scene, a lunchtime RAF concert at the National Gallery, cracked windows and naked walls speak of evacuation and fragility. Small moments of repose and of melody give voice to an unspoken vulnerability that is even more affecting in its contrast to the self-mythologised British spirit that is still trotted out by politicians ad nauseam after each successive violent event.

Cries of Britain standing united ring hollow throughout today’s sociopolitical landscape. Catastrophe has become an opportunity in which marginalised positions might be heard, as the Grenfell residents’ blog exemplified in many warnings which fell on “deaf ears”. In this state of confusion where voices feel lost and the country’s tower blocks are allowed to burn, the genius of Jennings feels so vital simply because his work does not speak for others after the fact but rather reveals something that was always there. He listened so that the rest of us might hear.

Published 30 Jun 2017

London Symphony is a collage of scenes capturing the richness and poetry of life in the British capital.

This 1966 TV play on a young woman’s descent into homelessness has lost none of its impact.

By Sam Thompson

Radical socialist filmmaker Marc Karlin emerged as a key counterculture figure in the 1970s and ’80s.