When François Truffaut saw Alfred Hitchcock’s penultimate film, Frenzy, he was of the opinion that it was a young man’s film. While the irony is obvious, in this singular moment Hitchcock had rediscovered his artistic youthfulness.

Only a year separates Hitchcock’s Frenzy from Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets, and during this narrowest of windows the same energy that rejuvenated an old master lit a spark for a future master of cinema. Both of these films exhibit a youthful exuberance that offers an impression of two individuals at different stages of their career, but with an abundance of energy to expend.

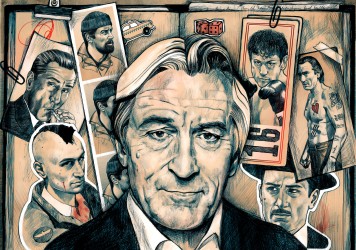

Now looked upon as a modern classic, Scorsese’s first full foray into the gangster genre sat on the cusp of his burgeoning youthful prowess. But rewind the clock back to 1973 and Mean Streets offered only an early impression of the great American filmmaker. Looking back on the early impression of Scorsese that Mean Streets offers, what is revealed is a musical and pictorial moment that has evolved throughout his body of work, alongside a reliance on interpersonal relationships that are a cornerstone of his cinema.

These have sought to draw our interest through a back catalogue of human dramas that touch upon self-sacrifice, loyalty, friendship and the familial. But equally the acknowledgement of the importance of Mean Streets serves to contextualise Scorsese as the artistic conscience of the New American Cinema.

The opening of Mean Streets transitions from pictorial subtlety to an explosive musical and visual aesthetic. Keitel’s angst filled voiceover reflections about repenting on the streets quickly transitions to the home video montage set to The Ronettes’ ‘Be My Baby’. From here the stage is set for the infusion in Scorsese’s cinema of the literary methodology alongside the powerful unity of music and image. From The Ronettes to the Big Band music of Goodfellas’ opening scenes and onto the classical repertoire through a collision of the glitz and glimmer of Las Vegas with Bach’s St Matthew Passion for Casino’s colourful titles, and Cavalleria Rusticana for Raging Bull’s poetic black-and-white title sequence. The way in which Scorsese marries moving image and sound infers his appreciation of film as not an exclusively visual medium, but a sound medium in equal measure.

The Ronettes home video sequence offsets the angst ridden opening scenes with a playful and light musical accompaniment, an approach that will be explored again by Scorsese. Consider Raging Bull’s title sequence, which is infused with both a swirling aesthetic beauty and foreboding sense of tragedy, and Goodfellas’ musical opening which offsets the dark undertones with a playfulness that allows us to enjoy the tragic tale of this flawed character who always dreamt of being a gangster.

Mean Streets represents a point of creative conception, although borrowing George’s Delerue’s Theme de Camille from Le Mépris for Casino’s rendezvous in the desert is a high point of the marriage of image and sound in Scorsese’s cinema. It is sprawling, fantastical and dreamlike that transports the poetry of motion to a whole new level. First there was Mean Streets and the home video aesthetic, and then there was cinema; a technological and aesthetic evolution.

Mean Streets is a tightly woven interpersonal drama centred around Charlie’s (Harvey Keitel) relationships with his family, his girlfriend Teresa, and his friend Johnny Boy. This interpersonal tension is threaded throughout Scorsese’s cinema, although of course if characters are a tool to tell the story then a lonely or isolated character cannot fulfil the storyteller’s purpose as the need for conflict inherently comes through interpersonal relationships. Scorsese’s cinema is memorable for deeply rooted interpersonal relationships of which he adds a twist.

The use of voiceover in Mean Streets, Goodfellas and Gangs of New York laces his cinema with a literary quality that connects protagonist and audience, forging a bond in the literary tradition, or as close as a film can come to entering the mind of its protagonist. Although dating back to Mean Streets this has been a pre-occupation of Scorsese’s that takes the interpersonal beyond the screen through this literary preoccupation to connect on a more intricate level with his audience.

Charlie is torn by the expectations of individuals that are compounded by issues of loyalty, friendship and the familial. These are the themes that crop up again and again in Scorsese’s cinema. The warning given to Charlie to be cautious of Johnny Boy is mirrored by Paul Sorvino and Ray Liotta’s father-son relationship in Goodfellas, when the former warns the latter to be cautious his mob friends do not lead him into trouble. Of course loyalty, friendship and the familial are cornerstones of the interpersonal drama of the archetypal gangster narrative, but even outside of the gangster chapter of his oeuvre the interpersonal remains thoughtful in what it has to say.

1982’s The King of Comedy is constructed around the awkwardness that derives from unrealistic expectations that Rupert Pupkin (Robert De Niro) has of Jerry Langford (Jerry Lewis), but also the latter’s conflicting relationship Lewis has with his fans as a celebrity. Meanwhile for Taxi Driver’s Travis Bickle his loyalty to the young prostitute Iris is a reflection on the individual’s self-sacrifice that mirrors the self-sacrificing nature of his protagonist friend Charlie in Mean Streets.

The timing of Mean Streets is of particular significance as following the collapse of the studio system and the emergence of the auteur theory, the directors had wrestled a degree of totalitarian or dictatorial control away from the producers. The 1960s and 1970s represent a moment of reinvention or reshaping of the American cinematic brand. It was in this fortuitous moment that Scorsese and his fellow Movie Brats emerged to enter the fray.

If, however, Scorsese was on the cusp of his burgeoning youthful prowess, then his contemporaries, notably Steven Spielberg and George Lucas were on the cusp of leaving their own mark or scar on the story of film, in a moment that divides film from movies, and art from spectacle. While Spielberg and Lucas remain known for dropping the blockbuster bomb, Scorsese’s personal dramas (Mean Streets and Taxi Driver), full of grit and a grainy image to accompany them, define his work in this period.

In the shadow of age and stature Mean Streets has a distinct feel; a product of its time and perhaps how Scorsese fitted into the turbulent New American Cinema in contrast to his contemporaries: Coppola’s larger than life cinematic vision of the mob and war, and the less personal but more archetypal storytelling through spectacle with the blockbusters that were just around the corner. While Coppola, Spielberg and Lucas all made smaller more personal films, the scale of their bigger productions overshadowed them.

For Scorsese, 1977’s underwhelming big production musical New York, New York has both been lost and dismissed in the shadow of these smaller and more personal films. This therein frames Mean Streets as an historically significant moment in his career, and the obvious first step in his gangster canon. But it also serves to frame Scorsese as the historic conscience of the personal for the New American Cinema.

Published 20 May 2015

Steven Spielberg’s beloved 1993 movie is about so much more than dinosaurs.

By Matt Thrift

Dirty Grandpa may be an indefensible dud, but the actor’s recent output is nowhere near as bad as everyone seems to think.

Wes Anderson’s brilliant debut, which turns 20 this month, channels the youthful spirit of Mean Streets.