In the first part of a new series, Lucy Brydon talks us through the early stages of her debut feature.

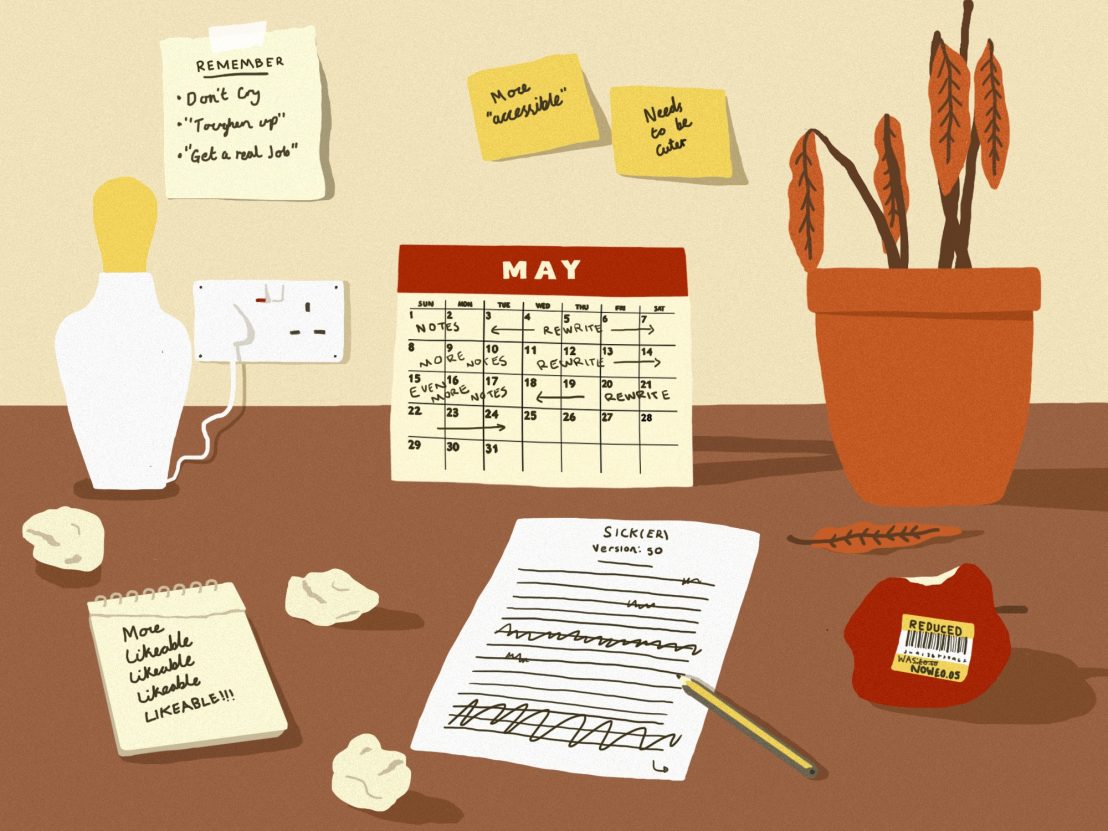

Being a filmmaker is the shit job that everyone wants. For every Pedro Almodóvar or Andrea Arnold, there are thousands of film school dropouts who are now producing digital content for your local financial institution. For the reckless few like me that hang on to the dream, there are years of development, rejection, ugly-crying in private (and occasionally in public), being told to ‘toughen up’ by people who don’t think your life makes any sense whatsoever, more rejection, and living on yellow-stickered supermarket catering. But seduction is about possibility, not probability. The more elusive measures of success are, the sexier they become.

I’m making my first feature film this year as a writer/director, so as you can imagine I’ve had a reasonable amount of time to ponder such matters in the contemporary filmmaking climate. The film is called Sick(er), and it follows a recovering anorexic in her mid-thirties, Stephanie, after she returns home from rehab as she tries to prove herself as a fit parent to her teenage daughter who now hates her. (It does have some funny bits in, I promise). The major roles are all written for women.

But to start from the beginning, Sick(er)’s existence is largely the result of a week-long boot camp as part of Film London’s Microwave scheme. Set up to give emerging filmmakers a platform to produce micro-budget films with a budget of £150,000, the Microwave scheme has previously released a range of critically-acclaimed productions including Lilting, iLL Manors and Shifty among others. The programme included several experienced mentors. The week was an intense and truncated version of what could otherwise have taken months in ‘normal’ development which is the process of readying a project for production.

We had discussions and feedback with our mentors several times throughout the week which led to frantic evenings writing and re-writing in response to their comments. This helped me to focus on exploring all elements of the script – breaking it all down and building it up again. This part of the process whittled down the 12 projects to a mere six. It’s particularly hard on writers, who had to edit and rewrite quickly. After that, we were selected to go through to the next stage of development, along with five other projects.

The next few weeks were very intense. The main issue was that the main character in my script was too inaccessible for an audience. This is a common complaint, and I have to say in my experience it’s too often levelled against female characters. The frustrating question is, ‘Why can’t she be more likeable?’

Fuck likeable. Likeable doesn’t make for a memorable character. Niceness doesn’t turn a cinema audience on. It’s just that we are culturally set up to demand female ‘likeability’ more than male. Besides, anorexia – so often identified with women, though increasingly noted as being an issue for men and transgender people – is a tricky thing to portray in an authentic way without softening it or making it seem in some way ‘glamorous’. I was drawn to writing about it because of personal experience, but I do recognise that there are a lot of people who may not understand why someone can’t just have a burger. I hope the film can go some way to adding to the narrative on the subject in an informed and compelling way – but I don’t want to offer trite or easy answers.

In May 2016, having made it through to the last stage, we were commissioned by Film London to go into production along with another project called Looted. The next few months were spent on a treatment – the writer’s nemesis – which is basically a prose summation of the entire plot of your film. In what has often felt like a protracted game of verbal Jenga, I worked on that until we finally moved back to script again in December. I have never been happier to type INT. STEPHANIE’S HOUSE – DAY in my life. But writing all those treatments had hammered out all the crap and left what was important. When I finished it, I had the sense that it was getting there. And I’ll take that.

Does development have to be hell? Any screenwriter will tell you that it can be. I often felt like my head was going to explode with the Groundhog Day-esque rhythm of notes, rewriting, and more notes. But what I have learned is that sufficiency in development is a case by case thing. It’s also about the people you work with; Angeli MacFarlane, the story editor at Film London, really got where I was trying to go before I could really see it myself and my producers have been endlessly patient.

Film projects can be developed to death, but without spending enough time with your characters, and allowing yourself to have breaks to create distance and perspective for the stand-out ideas, your Great Script Idea™ is going to fall flat on its arse. The main thing to hold on to when it gets tough – and it gets very tough – is the belief that what you are doing is significant, even if it’s just in some small way. That’s all any writer can really hope for. It’s why we do what we do.

Stay tuned for the next part in this series and in the meantime follow Lucy’s journey on Twitter @brydon_lucy

Published 16 Mar 2017

Five emerging filmmakers offer essential first-hand advice for how to bring your creative vision to life.

Director Tom Geens offers an essential eight-point guide to filming in exterior locations.

An aspiring filmmaker reveals how she set about channelling real-life struggles into her first script.