Words

Mark Asch, David Jenkins, Trevor Johnston, Matt Thrift, Ethan Vestby, Craig Williams

Illustration

From Yilmaz Güney to John Huston, read part two of our essential guide to the last films by famous directors.

There’s never been another filmmaker like Yilmaz Güney. On-screen the Kurdish-born firebrand specialised in moody Brando-esque roles in the ’60s. He then wrote and directed his own politicised neorealist movies, becoming an insurgent voice who was repeatedly imprisoned by military authorities throughout the following decade. Sentenced again for the murder of a state prosecutor, he continued writing scripts in prison (which were then shot clandestinely by his assistant Serif Gören), among them Yol, the joint winner of the 1982 Palme d’Or.

To date, he’s the only prizewinner to turn up having escaped from jail, allegedly pursued by Interpol. While in France he made one more film before dying suddenly of cancer, aged 57. Yol remains his testament. It’s no fist-pumping call to arms but a despairing picture of what he called ‘the moral debris left behind by feudalism and patriarchy’. Following various prisoners allowed home on leave, Güney shows us a Turkey gripped by army checkpoints, locked in a virtual civil war, yet choked just as much by its own repressive moral values and ingrained traditionalism. Complex, challenging and magnificently authentic, it’s a film to leave us asking why none of his work is readily available on DVD. Trevor Johnston

Of their five collaborations, Rio Lobo remains the picture for which Howard Hawks and John “The Duke” Wayne are least likely to be remembered. And rightly so. Hawks’ indifference to his material extends far beyond his complete abandonment of the film immediately after shooting. He flew straight to Palm Springs and played no part in its editing. The often wince-inducing, in-camera sloppiness feels a far cry from both the drum-tight rhythms of his ’30s and ’40s work, and the shaggy-dog looseness of his post-Rio Bravo best. Hawks brought in writer Leigh Brackett for a third (after El Dorado) reconfiguration of Rio Bravo’s jailhouse stand-off, but even the most ardent Hawksian would struggle to find much of interest beyond the most rote variations on this theme.

The opening train heist is handsomely mounted, but more often than not Rio Lobo feels like a half-hearted last stand; an anachronistic fuck you to the young turks riding in on horseback and motorcycle. John Wayne huffing, puffing and slapping women’s arses remains a craggy monolith carved from unreconstructed oak, but when Hawks famously said of The Wild Bunch, “I can kill four men, take ’em to the morgue, and bury ’em before he gets one to the ground in slow-motion,” few who agreed could be thinking of Rio Lobo. Matt Thrift

It’s incredible to think that Alfred Hitchcock’s directorial career started before Buster Keaton’s The General and ended in the year of Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. He was a silent pioneer and British maverick before developing into the signature stylist of his Hollywood prime. By the second half of the ’60s, though, he’d clearly peaked, and while 1972’s Frenzy marked a viciously provocative return to London, by then young pups like Brian De Palma were delivering better mock-Hitchcock than the old man might have managed.

Which is why the jaunty, decidedly urbane Family Plot is such a surprise, a gentle caper entangling a fake spiritualist and a fiendish diamond thief, its essentially comedic tone took Hitch back to ’30s British larks like Young and Innocent or The Lady Vanishes. True, the pace is certainly deliberate, yet the movie’s far from old fashioned, since the cast bring a quintessentially ’70s New Hollywood vibe to it. What with goofball vixen Karen Black in a blonde wig, Bruce Dern doing full-on whimsical as an inquisitive cabbie, and William Devane suave yet scary as the volatile villain, it’s a Hitchcock movie with a flavour like no other. Not a bad way for the 77-year-old to bow out. TJ

The cliché of the beloved director going out to seed, or losing his way in the final furlongs of an otherwise star-spangled career, is all present and correct in the case of John Hughes’ Curly Sue. It’s a film that’s so sickeningly sentimental that not even prattling Chicago dough-boy Jim Belushi can help toughen it up. And yet, watching it now, there is a defensible husk at the core of this story of two noble transients. It’s about Belushi’s Bob and his frizzily-mopped daughter, Sue (Alisan Porter), who makes up in mildly astringent barkeep patter what she lacks in formal education.

Kelly Lynch’s basic bitch lawyer takes pity on these lovable hucksters, and the film transforms into an essay on class consciousness which questions whether there is any way to bridge the cultural and economic chasms of ’90s America. There’s a sequence where the three go and see a Looney Tunes cartoon in the cinema (screening in 3D?), and Hughes attempts to leaven the film’s violent overtones by synching in comedy sound effects when characters are, say, run over, receive a serious head injury, or are simply booted in the swingers. We know how you feel, John… David Jenkins

Despite tackling a number of literary adaptations throughout his career, John Huston certainly saved his toughest customer for last. His final film would be The Dead, taken from James Joyce’s collection of short fiction, ‘The Dubliners’. By this point in his life, Huston considered himself an honorary Irishman having bought land and set up home at St Clerans outside Galway. One can feel the affection for his adopted country coursing through the film. It’s easy to see why Huston was tempted, given the sense of bittersweet celebration and doomed masculinity found in the text. Yet Joyce remains a writer whose work remains resistant to screen adaptation, and there’s little in Huston’s visual style that suggests previous success with such literary introspection.

So it’s remarkable that a film as often lumberingly flat-footed as The Dead – see the dance sequence – should also find such lucid moments of poignancy and grace, rendered all the more powerful by the fact they appear out of nowhere. Aided immeasurably by DoP Fred Murphy’s whiskey-dipped glow, and wonderful performances from Anjelica Huston and Donal Donnelly, it’s in quieter moments that The Dead soars more so than in the literalism of its overtly poetic finale. A small film of overwhelming power, you can feels Huston’s kinship with Joyce’s closing passage: “Better to pass boldly into that other world in the full glory of some passion than fade and wither dismally with age.” MT

Read part one of our guide to great final films by famous directorsThe tragedy of Satoshi Kon’s sudden demise to pancreatic cancer is the feeling that as a filmmaker, he was only just warming up. That’s not to say that titles already in the can such as 1997’s Hitchcockian J-Pop satire, Perfect Blue, or 2001’s exploration of Japan’s classic-era leading ladies, Millennium Actress, weren’t brilliant in their own right. It’s that Paprika seemed to anticipate and out-class Christopher Nolan’s Inception by some four years, and with it, Kon had passed through the looking glass, had found a way to make a purely experimental movie that carried the base emotional conventions of straight drama.

The film is about a contraption used to enter into the dreams of others with the aim of fixing psychological maladies. It gets into the wrong hands and all hell breaks loose. Kon’s handling of this interior battle between good and evil sets fire to the rule book then tosses the ashes into a canyon. The world and the movie business desperately need those whose ideas are unshackled from the bounds of banal human experience – people who can dream big and not stupid. Kon was one of the very best before he was snatched from us. DJ

Even Kubrick’s comedies are schematic and grandiose. His last film was elegantly, mysteriously so. In stately Steadicam shots, Tom Cruise’s lucky, limited doctor wanders a backlot New York that, with its Christmas lights and stilted interactions, is like a waking dream. Haunted by wife Nicole Kidman’s confession of an emotional life beyond his understanding, he chases a conspiracy of platonic shadows, whose Fellini-esque masked orgies offer tempting flickers of authentic knowledge.

Eyes Wide Shut is the culmination of the late-’90s run of brain-in-a-jar sci-fi flicks – Dark City, The Thirteenth Floor, The Matrix, virtual realities hinted at by movie- movie production design – crossed with Paul Bowles’ philosophy of death as transcendent truth: “Reach out, pierce the fine fabric of the sheltering sky, take repose.” Yet the film’s final moments are as touchingly earthy as any in Kubrick’s career. Mark Asch

It seems fitting that Madadayo would be Kurosawa’s final film, given its reflective nature. A gentle tale of a much-loved professor’s autumn years, it’s a quietly profound work that eschews the filmmaker’s characteristic propulsive narratives for something more contemplative, its title (meaning, ‘Not yet!’) a battle cry taken from scenes of lively birthday celebrations at which his students ask if he’s ready to die. It’s not the first of Kurosawa’s films to tackle questions of mortality, but neither does it frame its protagonist’s impending shuffle in explicitly sentimental terms like his earlier Ikiru.

There are no life lessons to be learned here, beyond the good humour and grace with which Tatsuo Matsumura’s professor awaits the inevitable. Flowing with all the properties of a final sigh, Kurosawa switches out his muscular editing patterns for a series of fades to black, his interior compositions more often appearing to echo the poise of his contemporary, Yasujiro Ozu than himself. An expressionistic final sequence can’t help but take on the sense of cinematic valediction for one of its true master craftsmen. MT

No, this 1983 Hollywood comedy doesn’t begin with Chevy, Eddie or Bill Murray making a pratfall accompanied to their star billing, but rather the words: “Jerry… Who Else?”. Despite America’s efforts to leave its clown laureate to the French, Jerry Lewis was back for one last directorial effort in which he stars as Warren Nefron, a klutz of apocalyptic proportions. In other words, a Jerry Lewis character. Yet the predicament that separates Nefron from Lewis’ other screen nerds like The Nutty Professor’s Julius Kelp or Herbert H Heebert from The Ladies Man isn’t based on the need for attention from a pretty girl – a motif that led to accusations of misogyny and narcissism throughout his career.

What Nefron hilariously fails at again and again through his klutziness is killing himself. Despite his inability to exit stage left as a performer and icon, Cracking Up didn’t end up being a testament to his immortality, but rather a bittersweet swan song. While the lack of a follow-up could be chalked up to Lewis’ poor health (he suffered a heart attack while in post-production) or likelier, the film’s lack of commercial appeal (it went straight-to-cable in the United States), it’s fitting that his finale embodies his famed belief that there was no gap between comedy and tragedy. Ethan Vestby

Cinematic Swan Songs: A-F | M-R

Published 5 Feb 2016

An alphabetic index of the most marvellous and memorable final movies from famous directors.

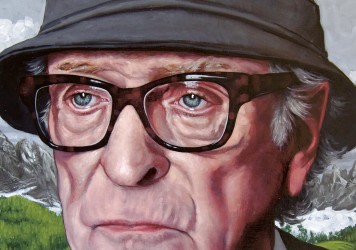

Take a look inside our latest print edition in which we meet British screen icon Michael Caine.

The French maestro has died at the age of 87, and leaves behind him an unimpeachable canon of work.