Words

Forrest Cardamenis, Phil Concannon, David Jenkins, Trevor Johnston, Jessica Kiang, Nick Newman, Justine Smith, Ethan Vestby, Craig Williams

Illustration

From Joseph L Mankiewicz to Eric Rohmer, check out the penultimate batch from our rundown of memorable last movies.

Despite a career that spanned four decades, which saw him win writing and directing Oscars two years running (for A Letter from Three Wives and All About Eve) Joseph L Mankiewicz is rarely mentioned in the same reverent tones as the Hitchcocks, Wilders and Fords of Hollywood’s classic era. The diversity of his output and his unobtrusive visual style perhaps make him less readily identifiable as an auteur (although Jean-Luc Godard’s first published criticism was a laudatory 1950 overview of Mankiewicz’s career). But one recurring Mankiewicz trait is dialogue that often yields great performances.

To that end, Sleuth is a fitting grace note. Based on Anthony Schaffer’s play, it’s about the cat-and-mouse games between a wealthy mystery novelist (Laurence Olivier) and his estranged wife’s callow lover (Michael Caine). It’s a tricksy, theatrical, not particularly “deep” film, and since its central gimmick cannot work a second time (and not even a first time really, to a Caine-literate modern audience), it could feel stagy and somewhat disposable. But because of Mankiewicz’ particular talents, Sleuth is in fact highly rewatchable, as two crackling performances deliver Schaffer’s witty, baroque words with just the right amount of self-aware ham. Jessica Kiang

Having made a name as a maestro of film comedy, with the likes of Marx brothers’ classic Duck Soup and The Awful Truth on his CV, Leo McCarey struck out big time in his twilight years with a string of whimsical faith-based “comedies” which are almost wholly lacking in the rapier sharp irony and visual exuberance of yore. In an interview with Peter Bogdanovich, McCarey admitted to not only despising the three stars of the awfully titled Satan Never Sleeps – William Holden, Clifton Webb and France Nuyen – but the actual production of the film itself, bowing out five days before it was completed and leaving the tidy-up to an assistant.

The film’s staggeringly non-PC plotline would likely cause the internet to implode if something of its ilk released today, with Holden’s rugged Christian missionary holed up in revolutionary China to spread the good word, while his trouser chasing cook (Nuyen) is raped by a Communist boot boy. The film is then about how Holden and fellow priest Webb go about rehabilitating the Communist so he can raise the child that he forced upon his unwitting female prey. The final shot sees rapist and victim christening their child and laughing heartily [sound of skin crawling]. David Jenkins

I remember going to see Don’t Make Waves at the London’s BFI Southbank, the decision to head down more because I wanted to watch something, anything, than any great affinity with its director, Alexander McKendrick. His “great” movies – The Ladykillers or Sweet Smell of Success – never really did it for me, so the impulse to make a point of catching Don’t Make Waves was mystifying to say the least. The film ended up being a major hoot, a riotous parody of flesh-parading west coast surf pictures which can now be seen as an important forerunner to Paul Thomas Anderson’s Inherent Vice.

“Turn on! Stay loose! Make out!” read the poster tagline for a film which sees Tony Curtis’ New York journo forcibly dunked into the deep end of seafront hippy culture, free love, surfing, sky diving, and a beachfront houses with poor foundations. It’s a very funny and flip film which miraculously manages to sustain its wild sense of humour until the last. Even though Don’t Make Waves was made in 1967, MacKendrick never made another film, instead accepting a cushy job at the famous Cal Arts institute as the Dean of Film, and died in 1993 at the ripe old age of 91. DJ

Not to second guess the sleuthing skills of our readers, but were you to watch Jean-Pierre Melville’s Un Flic shorn of all context, it’s unlikely that you’d guess it was the director’s final movie. There’s the sense that he’s attempting to court a more mainstream audience, as it not only boasts two of France’s most beloved stars – Alain Delon and Catherine Deneuve – but Rambo’s Colonel Trautman himself, Richard Crenna, potentially in a bid to lure in American cinemagoers. The story of a team of crooks bungling a bank robbery and, later, a drug heist on a moving train, does that Melvillian thing of lightly romanticising the skill-sets of cads and robbers while celebrating the intricate and exotic processes they develop to execute their schemes.

In the film’s central set piece, Crenna is lowered onto a moving train from a helicopter, and stealthily breaks into a compartment to nab two briefcases full of drugs. To bring this scene to the screen, Melville uses some sneaky illusions of his own, bringing in a model train set, remote control helicopter and smoke machine to offer an effect without shattering through budget constraints. In that sense, this is an impressionistic gangster film – a story of debonair crooks that’s been made by one. DJ

When it comes to cracking through the smiley façade of American picket fenced suburbia to reveal violence, vice and transgression, David Lynch is your go-to guy. However, roistering bosom man Russ Meyer used his final movie to assure that if you enter into any house on any street in what he and screenwriter Roger Ebert refer to as “Small town America”, you’ll be party to scenes that are hotter than a Mexican’s lunch. Junkyard dogs, religious radio announcers, blue-eyed decathletes and horny, hairy clock punchers manage to find ways to slot aggressive sex into their daily routines.

It’s an openly, barbarically lewd picture, but Meyer manages to transform the material into a work which wouldn’t look out of place as a video installation at an art gallery. Every shot is intricately framed, and the exuberant editing patterns and detailed visual coverage suggest a man with a precise vision of what he wanted to achieve. At the climax of this breathless sex montage movie, Meyer himself appears, realising that his entire crew has walked out on him. The randy bulldog of big screen titillation bids a fond, personal farewell to his audience, as their eyeballs are harvested by the demon of cheap, tacky, mass-market VHS bongo. DJ

It’s rare that anyone would associate Kenji Mizoguchi’s films with anything close to cheeriness, but even a familiarity with his dark work wouldn’t prepare a viewer for his final film, Street of Shame. Moving away from the period settings of his best-known work and into the modern world, Mizoguchi put his eye – an eye that, above all else, understands the visual significance of myth and iconography – on a matter that few, even 60 years on, will directly confront: sex work, prostitutes, and the unfathomable pain that their lives can yield. The fusion of clean framing and editing with legitimate horrors make this film even more tragic in how they hint at what work might have followed. It’s one of the great dramas of postwar Japan, a film that can be turned over and debated even to this day. Nick Newman

When we talk about the grand masters of postwar Japanese cinema, two names often arise: Yasujiro Ozu and Kenji Mizoguchi. Thanks to DVDs and clandestine networks of online cinephiles, Mikio Naruse is now a name that can be added to that extremely refined list. Scattered Clouds (aka Two in the Shadow) is Naruse’s parting gesture, and there’s no doubt that it stands up as a film which deserves a place alongside the likes of Ozu’s Tokyo Story or Mizoguchi’s Ugetsu Monogatari. It follows a theme the director often returned to: the idea of two people being in love with one another, but never both at the same time.

Mishima (YûzûōKayama) accidentally runs over and kills a man who happens to be the fiance of Yôko Tsukasa’s Yumiko. He agrees to pay her financial support by way of an apology, and over time, an impossible love blossoms. However cordial and loving this man can be, will the association with death ever escape him? Are people fated to be defined by their actions? And can we suppress those dark associations in the name of love? Naruse’s diplomatic answer to this question is that humans are beautiful and complex creatures, and to answer that conundrum would be unlock the secret to life itself. DJ

Catch up with the first part of our guide to great cinematic swan songsA friend’s remark that the economic crisis should compel him to make a film about poverty was the reported inspiration for Manoel de Oliveira’s final film, Gebo and the Shadow. It is worth mentioning, however, that his very first film in 1931, Labor on the Douro River, was a look at industry and poverty in his hometown of Porto, Portugal. A silent short portrait of a town, Labor… could not be more different from Gebo, a feature-length, digitally shot, single-setting story with four main characters and just nine in total.

Gebo includes numerous shots that run for 15 minutes and are lit without the excessive artificial lighting that shooting on film demands. It is no coincidence, then, that light becomes the film’s central metaphor, with sunlight signalling the isolated family’s entrance into a world of corruption. Eighty years did not stop the 103-year-old director from turning the specific properties of new technology into his film’s defining virtues. Nothing suggests the work of a master, like an exit so similar and yet so different to his entrance almost a century earlier. Forrest Cardamenis

Critic Andrew Sarris once declared, “Lola Montès is, in my unhumble opinion, the greatest film of all time.” But upon its release it was critically maligned and for years only a heavily cut version was screened. Told through flashbacks, Lola Montès is a romance that focuses on the beats of regret. It’s about this fantastic woman who did fantastic things and fell in love with fantastic men, but lived to see it all fall apart.

As one of the true great tragedies of the screen, the film uses shrill audio and visual flourishes to raise Lola to the realm of mythology. Like Icarus, who flew too close to the sun, the camera itself does the impossible in charting Montes’ rise and fall. Ophüls’ work, which has always involved a moving and spinning camera, never felt so magical and so effortless. While the film has a grand scope, spanning many decades and crossing continents, its greatest appeal lies in its intimacy with Montes’ passion and solitude. Justine Smith

The title translates as Taboo, prime territory for director Nagisa Oshima until ill-health eventually ended his filmmaking career. Having deconstructed narrative as he dismantled Japanese social mores, Oshima brought hardcore sex into the art-house mainstream with Empire of the Senses and paired Charlotte Rampling with a frisky simian in Max, Mon Amour. Where could he go after all that? To some extent Gohatto revisits the homoeroticism in war which marked 1982’s Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence, here framed within a historical drama about the pro-Shogun militia, the Shinsengumi. The rigid discipline that is key to their operation is destabilised by the arrival of androgynous Ryûhei Matsuda, who stirs yearning throughout the ranks, even in stoic lieutenant Takeshi Kitano.

Oshima teases with hints of conventional action choreography and writhing physicality, yet his approach also matches the military’s controlling mindset by deliberately withholding key scenes and filling story ellipses with pared-down intertitles. This distancing effect forces us to consider the story’s contemporary ideological relevance, most strikingly in the climactic slashing of a cherry tree suggesting that modern Japan’s rigid social consensus is at odds with its own unruly desire for beauty. Far from Oshima’s most ferocious offering, yet its steely resolve is rewarding. Trevor Johnston

One of the most controversial films ever made, Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom was Pier Paolo Pasolini’s critique of Italian fascism, and it encapsulates his communist and anarchist views held throughout his career. Pasolini was murdered shortly after the film was completed, with suspicions that he was targeted because of his politics. Based on a story by the Marquis de Sade, whose philosophy celebrated hedonism, Pasolini associates the pursuit of pleasure with evil. If absolute power corrupts absolutely, then upper classes, comfortable in their material wealth, inevitably dehumanise and abuse those who beneath them?

Challenging audiences by featuring young victims beaten, used as slaves and forced to eat their own faeces, Pasolini’s film dares us to look away. The rise of hedonism suggests that fascism is not a quirk of “evil” but is possibly ingrained in human nature, or at the very least a symptom of capitalism. Evil in the film is a scapegoat, a way to explain away our responsibility. The horror of Salo is that it does not exist outside the realm of possibility – it is a heightened reflection of the evils of which we are all capable. JS

Situated far from the working-class milieu of his first film, 1968’s L’Enface Nue, Maurice Pialat’s final work stars his favourite actor, Monsieur Depardieu as (who else) Gerard, a charismatic, quasi-bourgeois with his attention divided between his four-year-old son, Antoine, his ex-wife Sophie, and his various girlfriends. Life is further complicated by his potential romantic adversary, Jeannot – Sophie’s new partner. While on his occasional visits he may shower his son with gifts and retain at least some form of connection with Sophie, as someone settling into middle-age, Gerard’s tenuous relationships can’t help but make his happiness utterly uncertain.

Yet even with all the required emotional turmoil, Pialat creates levity through bouts of movement, such as a dancehall sequence from his otherwise appropriately downbeat biopic, Van Gogh, which sees a modern day equivalent in a synchronised waltz scored to both Bjork’s ‘Human Behavior’ and, yes, Corona’s ‘The Rhythm of the Night’. Simpler, if just as effective; Gerard taking his far-too-small son around on his motorcycle, or Antoine in his new toy car noisily circling around his mother’s spacious apartment. These are, in pure Pialat fashion, the kind of brief snippets of time that only heighten the sting of the eventual and far-too-abrupt cut to black. Ethan Vestby

For a director who spent much of his career exploring the concept of crumbling manhood, this courageous kiss-off, which was co-directed by Wim Wenders, sees Nicolas Ray turning the camera on to himself. Riddled with cancer, but never without a smouldering cigarillo between his lips, the physically fragile legend muses artfully and obliquely on his career and his impending expiration, all the while playfully slipping between reality and artifice, delirium and calm.

The title refers to a film Ray wants to make about a man who sails to China to find a cure for his mysterious ailment. Shots and motifs are explained to Wenders, who attempts to recreate fragments in posthumous reverence to his friend and mentor. While Ray remains understandably cantankerous, dryly humorous and invigoratingly poetic through the film’s first half, his health starts to falter as the film comes to its frenzied close, and the unmatchably sad final take is just a shot of Ray – with eye patch – monologuing incoherently before aggressively daring the cameraman to cut. DJ

Satyajit Ray knew The Stranger was going to be his final film. Still suffering from the debilitating effects of a heart attack years earlier, Ray wrote the screenplay in his sick bed and directed much of the production from inside an oxygen tent. Despite the knowledge of his death being imminent, The Stranger is not presented as a grand final statement; instead, Ray’s last work is an intimate and engaging character-driven drama set almost entirely within the confines of a single location. His story is a simple one that accumulates metaphorical weight. Utpal Dutt is the stranger of the title, a man who unexpectedly turns up at the home of middle class couple Anila and Sudhindra (Mamata Shankar and Dipankar Dey), claiming to be Anila’s uncle, a long-forgotten character who left the family 35 years earlier to explore the world.

As the sceptical family interrogates this interloper, he spins them a series of tales from his global travels, none of which make clearer whether he is who he claims to be, or if he’s simply a very skilled conman. In fact, it is those asking the questions who end up revealing more of themselves through this process. Throughout The Stranger Ray observes his characters at close quarters, his camera moving around the family home with effortless grace. His ability to find humour and pathos in every human interaction had not deserted him at this late stage. The Stranger might be viewed as a minor work, far from the scale of Ray’s masterpieces, but it is a rich and engrossing film about trust, judgement, understanding and – fittingly for this great director – the power of storytelling. Phil Concannon

The Little Theatre of Jean Renoir gets barely a page of consideration in the French director’s brilliant and eloquent memoir, ‘My Life and My Films’. When mentioning it he channels a certain frustration, as this trio of short moral tales (plus a midpoint sing-song) was made for TV after, “seven years of unwilling inactivity”. Having set his own creative bar stratospherically high with classics like The Rules of the Game, The Grand Illusion and The River, it’s hard to see this climactic statement as more than a compendium of odds and ends.

But the film was put together with the same verve and essential human compassion that characterised everything the great man put his hand to. The second chapter is a bizarre techno-operetta, and the finale is a moderately successful colloquial farce. Though it’s the surprising opening chapter that hits home the hardest, initially looking like a sentimental live-action Disney film about the fantasies of homeless pensioners left in the snow for Christmas. Just as you think they’re going to rise up out of their riverside hovel, they freeze to death, their belongings are stolen and the film ends. DJ

When Life of Riley premiered in competition at the 2014 Berlin Film Festival, even seasoned Resnais acolytes were left a little underwhelmed by this self-consciously theatrical Alan Ayckbourn adaptation. It sees a group of people rehearse a play while a close friend, George Riley, suffers from a fatal illness in the background. When the director passed away barely a month later, the film was suddenly seen in a very different light, its intentions perhaps more vivid than they were when its creator still walked among us.

The film openly inspects the links between life and art. Artifice is emphasised at every turn through brash performances, the stripped back, vibrantly-coloured sets, the use of “off-stage” space, and even knowingly bad special effects in the form of a toy badger that’s digging holes in the lawn. In bringing together members of his regular repertory company – Hippolyte Girardot, André Dussollier and his widow, Sabine Azéma – it becomes clear that George is a stand-in for the director himself, a character whose unseen hand appears to be guiding the lives – artistic and emotional – of all around him. DJ

To say the least, the final movie by one-time Nazi totem and cine- ethnographer Leni Riefenstahl is extremely unexpected. In 2002 and at the age of 100, Riefenstahl addresses the camera as a preface to her 45-minute documentary, Impressions of the Deep, explaining that the film we’re about to see has no narration and that the images are vivid enough to speak for themselves. The upshot of a later-life fascination with Scuba diving and undersea exploration, this Cousteau-like montage of exotic sea life swimming in and out of pulsing coral shelves is simple, neat and pleasurable. It confirms Riefenstahl’s promise as a maker of arresting images.

Naturally, this is a more superficial work than, say, Triumph of the Will, and it’s not helped by Giorgio Moroder’s dire Muzak score in which he uses synthesiser effects as commentary on the fish captured on camera (example: when a fish whose skin resembles a decorative Japanese garment, Moroder breaks out the koto sound effects). Riefenstahl herself features in the final minutes, and the moving climactic shot observes as she swims up to the surface, directly towards a white light beaming down from above. She died the following year. DJ

The Romance of Astrée and Céladon is more of an epilogue to Eric Rohmer’s career than a swan song. If we take Rohmer’s oeuvre as an extended conversation about the romantic lives of young people in modern France, then An Autumn Tale – his final contemporary-set picture – is the film that closes the cycle, with the three historical films that followed serving as reflective afterwords. The Romance of Astrée and Céladon still focuses on young love, but its central concern is the way we frame stories around it; the creative mechanics behind the art of love.

At its heart, the film shows how each era’s storytelling customs ultimately obscure the essence of romance. Though Rohmer’s films were meandering and discursive, they were often structured like age-old parables. This film slyly deconstructs this approach, with elaborate period clichés – fair maidens and Sapphic sirens – comically pronounced and exposing the artificiality of each generation’s storytelling devices. And yet it’s hard not to get swept up in the woozy mysticism of Rohmer’s fable. The director evidently surmised that, in constructing narratives around love, we enhance its mysterious power. Perhaps this is the key to his entire body of work? Craig Williams

Cinematic Swan Songs: A-F | G-L

Published 5 Feb 2016

An alphabetic index of the most marvellous and memorable final movies from famous directors.

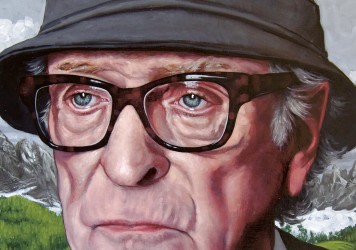

Take a look inside our latest print edition in which we meet British screen icon Michael Caine.

From Yilmaz Güney to John Huston, read part two of our essential guide to the last films by famous directors.