Words

Adam Cook, Simran Hans, David Jenkins, Jessica Kiang, Nick Newman, Craig Williams

Illustration

An alphabetic index of the most marvellous and memorable final movies from famous directors.

We take for granted that when we wake up of a morning, art will be there for us to consume. And that our favourite artists will be there, ready and willing, to serve this unquenchable desire. But time is a cruel mistress, and just as, say, a film director has to make a first movie, he or she will also have to make a final movie.

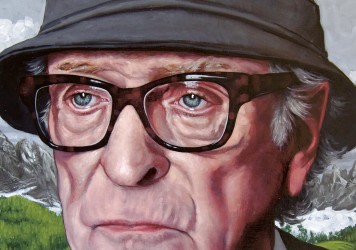

Our latest cover film, Paolo Sorrentino’s Youth, is about a retired conductor (played by Michael Caine) who is looking back over his life and working out which loose ends need tying, and which can remain forever frayed. With that in mind, we’ve decided to take 50 examples of cinematic swan songs and explore them individually in search of common themes and threads.

On occasion, a director will accept their mortality, creating a work that translates into a grand statement on a life lived and a corpus completed. Other times, we see reliable filmmakers who treat creating art as a job – a way to pay the bills – and they continued to carry this out until they found themselves stiff in a box. There are also examples where tragedy intervenes to stop a great artist in their tracks, making what some may have seen as an exciting new direction into a unpredicted exclamation of finality.

It seems sad to have to kick things off by writing about Chantal Akerman’s No Home Movie, not least because its swan song status was calcified so recently and so abruptly. The film was booed at its press screening at the 2015 Locarno Film Festival, and opportunist hacks later crassly speculated that this had a direct link to the director’s suicide two months later. Had those same hacks actually watched the film, they would’ve seen an extraordinarily moving and unguarded portrait of loneliness and existential bemusement as Akerman’s beloved mother deteriorates physically and mentally in front of her hand-held camera.

As final movies go, this one seems archetypal, drawing on her formative classics such as 1975’s portrait of enforced domesticity, Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, and more directly from 1977’s magnificent News from Home, whose narration comprised of concerned letters from Akerman’s mother as the director plied her trade in New York City. The opening long shot of a fragile tree being blown to breaking point by strong winds says it all. David Jenkins

Much like Alain Resnais’ Life of Riley, a film which appears to acknowledge that its maker knows his time is almost up, Robert Altman’s A Prairie Home Companion is a cavalcade of pure, downhome pleasure, but with a seriously bittersweet undertow. The film offers a fictional chronicle of Garrison Keillor’s famous, long-running live radio broadcasts from which the film takes its title – a broad mixture of teatime comic high-jinx, gather-round-the-hearth anecdotes, folk songs and miscellaneous merriment.

The show we’re watching is actually the final broadcast, and the old theatre in which it takes place is set for demolition the following morn. Convention would have it that some scheme needs to be executed to save the building and, by extension, preserve this grand old American tradition, but no-one seems that fussed about letting it slip away in the name of modernisation. Notable for a superb supporting turn by Lindsay Lohan, plus the patented Altman dialogue, which overlaps with itself like gentle waves as the tide flows out. DJ

Michelangelo Antonioni may not have known that The Dangerous Thread of Things, from the 2004 omnibus picture Eros, would be his final work. It’s a take on those plotless, “pretentious” films about aimless rich people, and as a swan song, it fits the bill.

At 91, the Italian titan was rendered incapable of speaking and partly paralysed by a stroke, but nevertheless produced this essentially silent featurette, a woozy union of experience and perception that asks us to devote no less attention to a glass rolling across a restaurant floor than it does two lovers whose quarrelling is the only ostensible human subject matter. What’s more important is that we look, hear and feel everything presented to us. The bizarre inner logic of the film becomes clear in the closing moments as nearly identical nude women observe one another on an empty beach – which may, all told, be the most purely serene moment in the director’s entire oeuvre. Nick Newman

You can’t keep a good man down, and having announced that 1982’s Fanny and Alexander would be his final film, Ingmar Bergman came back for one last (gentle, observant and meticulous) roll of the dice. 2003’s Saraband is an addendum to one of his great works – 1973’s Scenes from a Marriage. Yet instead of diving straight back in to the sharp rhetorical parrying of that film – in which Liv Ullmann’s Marianne and Erland Josephson’s Johan argue for the best part of five hours – the stirring Saraband stages a reunion highlighting the hideous lives of offspring and kin and how our heroes may have failed as both partners and parents.

The film opens and closes on Ullmann scanning a table of photographs and addressing the camera directly, and even though she was the emotional entry point in Scenes…, she professes to being lonely and unfulfilled despite her professional success. The film looks at Johan’s son from another marriage and his daughter, the former a widower and both musicians with an unhealthily close relationship. There’s an abundance of psychologically meaty material here, and Bergman, ever the light-fingered master, enhances it through making the film about how people interpret and deal with bonds they perhaps don’t fully comprehend. DJ

The final shot of Luis Buñuel’s final feature sees its two main characters randomly blown up by terrorists. But the way it is shot (you only see a fiery mushroom cloud) you could construe this as the director gleefully detonating the entire planet as a mischievous parting shot. A cine-rascal ’til the last, Buñuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire is perhaps a belated mission statement, as many of the films within his exceptional canon focus on the idea of arrogant, entitled people being unable to fulfil simple desires.

Here, Fernando Rey’s wealthy flaneur Mathieu clasps his eyes on lissom maid Conchita during a dinner party (played in alternate scenes by Carole Bouquet and Ángela Molina) and decides that he must have her. Initial gentlemanly advances swiftly give way to bald financial transactions, though Conchita will simply not let Mathieu into her sewn-on girdle. It’s a scalding tract on notions of social entitlement, machismo, pretension and those (men) who are so overwhelmed by their own lofty status that they can’t see the world falling apart around them. DJ

Claude Chabrol almost made a film a year from 1958 until his death in 2010. Given how extraordinarily prolific he was, his final picture was never going to be a self-conscious swan song. And yet his death inevitably enhances certain traits in his work, elevating a deceptively simple policier to the state of elegy. The director considered Bellamy to be like a novel that Georges Simenon never wrote, a film in which Gérard Depardieu’s titular police inspector finds himself drawn into a case while holidaying with his wife. Though Chabrol only made two direct Simenon adaptations, the author’s spirit found its way into so much of his work.

By creating his own version of Chief Inspector Maigret, Chabrol bridged the gap between Simenon’s world and his own. The crime itself in Bellamy is almost a side note; as always, Chabrol’s interest is in the hopes, fears and desires of his characters. As the critic Armond White noted, genre was Chabrol’s MacGuffin. The film concludes with lines by WH Auden which speak not only to the events therein, but to Chabrol’s entire body of work: “There’s always another story / There is more than meets the eye.” Craig Williams

Though hardly counted among Charlie Chaplin’s great works – when, indeed, it’s counted at all – A Countess from Hong Kong is a far sharper sign-off than many think. In Countess, Chaplin himself has only a bit part, which is a little more than 1923’s A Woman of Paris where the auteur-performer’s presence was entirely absent. Some folks would be hard pressed to see a Chaplin film as a Chaplin film when the man himself is not smack-dab in the frame. And in this case, it’s hard to blame them: wide-screen, colour, Marlon Brando in the lead – this is hardly the ingredients of a Chaplin classic. And yet, as critic Andrew Sarris claimed, it’s “the quintessence of everything [Chaplin] has ever felt.”

This mournfully comic tale of an unhappy diplomat, his cold wife (Tippi Hedren) and a firecracker stowaway (a never-better Sophia Loren) is one of deep longing, encapsulating a clash between idealism and the cynical world of money and politics that threatens it. Career obsessions with class issues and the language of gesture, plus a sheer mastery of form make A Countess from Hong Kong one of his most deeply-felt films, the swan song of an old man who lived a life dashed with equal parts passion and disappointment. Adam Cook

There’s a documentary profile of the late, very great director, artist, activist and champion of independent film, Shirley Clarke, in which the camera darts around a throw pillow conversation circle. Jacques Rivette sits grinning as the star waxes poetic about her idiosyncratic project. This state of perceived comfort penetrated all of this unheralded director’s film work, from crackling drug fix drama The Connection, to florid confessional Portrait of Jason and on to her climactic documentary work, Ornette: Made in America, about free jazz saxophonist and composer, Ornette Coleman.

This film, which innovates with form in the same way its subject did, is about the process of making music, but it’s also about how artists talk about themselves and create an image they present to the world. Clarke’s genial presence is journalistic though she never hectors, managing to tease out personal, private and profound details from Coleman, including the intertwining of his convention-busting musical odyssey with the fact that he once physically attempted to suppress all erotic desire from entering into body and mind. Clarke died in 1997, leaving behind a petit, ugly/beautiful body of work that we should cherish. DJ

The career of the late Jacques Demy can be sliced roughly down the middle. Everything from 1961’s Lola to 1970’s Donkey Skin is great, everything from 1972’s The Pied Piper to his final film, Three Seats for the 26th, from 1988, is of variable quality. The stand-out in that shaky latter period is 1982’s A Room In Town, though his of-its-time and hearteningly sincere swan song, Three Seats…, does have much to recommend it. The film is an electro-pop love letter to working class chanteur (and sometimes actor) Yves Montand, who has returned to his hometown of Marseilles to star in a gaudy musical extravaganza based on his life.

Though this might seem of marginal interest to those not up with Montand, Demy’s character becomes a personal surrogate, dredging up and exploring themes from the director’s own classics – the melancholy rapture of French provincial living, fiery affairs extinguished by time and distance, reunions with family and loved ones through happenstance, and the sheer joy of singing and dancing in public. DJ

It’s only after watching Carl Theodor Dreyer’s imperious and imposing oeuvre in its entirety that you see that the director’s project was one of refinement. He came tantalisingly close to finding the primordial essence of pure cinema on many occasions, not least in films like 1955’s Ordet and 1928’s The Passion of Joan of Arc. However, it’s his gently devastating parting shot, Gertrud, which stands as his most breathtaking, nuanced and radical masterstroke. “A woman’s love and a man’s work are mortal enemies.” It’s a garish, off-hand sentiment which nevertheless colours the life of tormented society dame, Gertrud (Nina Pens Rode), whose search for a form of pure and selfless love goes tragically unfounded.

Though theatrical in its basic scene construction, Dreyer’s shattering masterpiece is boldly cinematic in its composition and lightly expressionistic in its performances. During long dialogues actors stare not at each other, but into some mysterious middle distance void, in a film about the impossibility of attaining strict gender equality in heterosexual relationships and, thus, being unable to see eye to eye. The film was loathed when it was originally released – dismissed as antiquated and stuffy. It has, of course, since grown to be recognised one of modern cinema’s most emotionally bracing achievements. DJ

The godfather of the modern movie montage set fire to his own playbook in this Mexican adventure which cinema lore dismissed as a muffed-up folly. Though intended as a puff piece quickie by the film’s local producers and paymasters, Eisenstein had other ideas. He shot away to his heart’s content and – on the evidence of the morass of images – tried to tell the unvarnished truth about an impoverished country in the midst of political and cultural upheaval.

While features such as Battleship Potemkin represent the innovations of early cinema, ¡Que viva México! comes across as a film that could’ve been made in the 21st century. And that’s not a comment on its subject, more an admission that it feels sprightly and modern. Some commentators have even pegged it as an early surrealist film. Pooh-poohed by some because Eisenstein’s footage was belatedly edited by one of his creative partners, Grigori Alexandrov, and thus not “strictly” part of the director’s body of work, it remains a fascinating and singular film, whatever its auterist credentials may be. DJ

Rom-com queen Nora Ephron directed just eight films, though she wrote twice as many (the 2000 John Travolta flop Lucky Numbers was the only one she directed but didn’t write herself.) Her last film, 2009’s Julie & Julia, focused on the parallel careers of two women, sidelining the love stories on which she made her name. Yet in many ways, this film is the most personal the writer/director ever made. Firstly, it reunited her with long-time muse Meryl Streep with whom she collaborated as writer on Silkwood and Heartburn. Secondly, it gave her the chance to pay cinematic homage to a subject she regularly wrote about in both newspapers and novels: Food.

Set against the backdrop of post 9/11 New York, it follows the gastronomic journeys of food blogger Julie Powell (Amy Adams) and her culinary inspiration, the celebrity chef Julia Child (Meryl Streep) – both sous-chef their respective ways to self-actualisation. While Julie and Julia perhaps doesn’t offer the same pleasures as Ephron’s classic romance films – sadly absent are the autumn leaves and Ernst Lubitsch-esque screwball patter – it does argue that women amount to more than their love lives. Simran Hans

Read part two of our guide to great cinematic swan songsThere would have been a certain grim poetry had Veronika Voss been the great Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s final film. It concerns a crumbling celebrity whose drug dependency expedites her tragic demise. But instead it was to be Querelle, made in 1982 from a beautifully lurid book by Jean Genet and released after the director’s death in June of that year. With its snow-globe set design – a Brest port lined with phallic bollards – and a dreamy choral soundtrack by the director’s long-time musical collaborator, Peer Raben, the film stands alone within the director’s oeuvre as a fantastical fairytale with gay romantic trappings.

It’s almost like a more brassily subversive Jean Cocteau movie. It’s possibly Fassbinder’s most invigoratingly visual film, one in which every fight, every act of aggression and flurry of naked passion translates into a dance or mating ritual. Bodies glisten in the golden sunsets, and Fassbinder uses every trick in the book (and some new ones) to enter the mind of his murderous hero. DJ

Spoiler: the closing scene from John Ford’s 7 Women is one of the greatest final sequence of any filmmaker’s career. The icy, life-hardened protagonist DR Cartwright (a marvellously brash Anne Bancroft), is in an impossible situation and held captive at a Christian mission. Having handily picked apart the foundations of the mission’s residents, one value at a time, she then sacrifices her life to save the people around her. At odds with the seven women of the film’s title (she not counted among them), the atheistic DR is brought in as a desperately needed doctor, and not long after her arrival, a company of Mongolian savages take over. She offers herself as a concubine to their leader to spare the others, a great example of a lone Fordian outsider acting on behalf of the greater good.

Ford spent a lifetime looking at how individuals find their place within society at large, and with 7 Women he arrives at a troubling and powerful act of martyrdom, thus closing a rich oeuvre on a note of devout existentialism — abruptly turning away from society or nation, and towards a relationship with one’s self and the universe. Like so many last films, this one concerns death — not ageing, but dying, and by extension, how to live. Every moment is integral to its purpose, communicating emotions and ideas with devastating aplomb. A swig of poison, the extinguishing of a light, the ignition of Ford’s most bluntly philosophical proposition. The End. AC

Bob Fosse’s most substantial legacy is as a Broadway choreographer/ director, but his five feature films suggest that theatre’s gain was cinema’s loss. His debut, Sweet Charity is strong, and Cabaret, Lenny and All That Jazz are Best Director-nominated touchstones (he won for Cabaret). And then there’s Star 80, as close to overlooked as a film representing one fifth of an Oscar-winning director’s output can be. Delivering a tabloid-sleaze salacious story with extraordinary compassion and insight, it tells of the tawdry murder of 1980 ‘Playmate of the Year’ Dorothy Stratten (Mariel Hemingway) by her estranged husband Paul Snider (Eric Roberts).

The performances are outstanding: Roberts’ Snider is a volatile cocktail of fury and inadequacy, embodying the inchoate violence of a Travis Bickle and the hopeless famewhoreishness of a Rupert Pupkin (reportedly, Fosse once circled The King of Comedy). And Hemingway is a revelation, heartbreakingly evoking Stratten’s dawning self-worth that wars with her misguided sense of gratitude, en route to an almost unwatchably visceral climax. Fosse had plans to direct other films that never came to fruition, but Star 80 deserves to be reclaimed as an uncompromising example of his chilling, incisive investigations into fame, image and destructive ego. Jessica Kiang

Cinematic Swan Songs: G-L | M-R

Published 4 Feb 2016

Take a look inside our latest print edition in which we meet British screen icon Michael Caine.

From Yilmaz Güney to John Huston, read part two of our essential guide to the last films by famous directors.

The British screen icon reflects on his remarkable career ahead of his starring role in Paolo Sorrentino’s Youth.