John Carpenter agreed to direct 1983’s Christine at a time when plenty of other directors were willing to board the lucrative Stephen King adaptation train. He wasn’t so hot on the idea of making a film about a killer car, but Carrie, Salem’s Lot and Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining had all fared respectably, and the American author’s bloated novels – this was King’s ‘lines of cocaine with a six-pack chaser’ period – were at peak popularity. The same year saw the release of David Cronenberg’s The Dead Zone and Lewis Teague’s Cujo. To paraphrase horror historian Carlos Clarens, there sure was money to be made in them there thrills.

Coming off the back of his expensive remake of The Thing – at the time critically reviled, barely scraping its budget back – Carpenter needed a sure thing and a movie based on a Stephen King novel seemed just that. In Hollywood, of course, you’re only as good as your last movie, as the famous saying goes. Today, The Thing is revered as a masterpiece of genre cinema, in large part due to the still-spectacular special effects work by Rob Bottin: hellish sculptures of gloopy, slimy, twisting tortured flesh, limbs and innards. In 1982 Rolling Stone magazine told its readers that the remake couldn’t “hold a candle to Howard Hawks’s trail-blazing 1951 classic The Thing from Another World.” A movie few people remember today, despite it featuring an alien with a carrot for a head.

While Carpenter has spoken in the past about “screwing up” Christine and described it as his least favourite work, the film has since received plenty of reappraisal and ranks among the best King adaptations. While very much a horror story about the American fetishisation of automobiles and consumerist materialism, to modern eyes it reads more like a prophetic vision detailing the rise of geek power and how such once-pitied figures turned out to be just as susceptible to corruption and mean-spiritedness as all the rest. Finding out a former bully has been murdered, “the kid was cut in half Arnie, they had to scrape his legs up with a shovel,” Arnie replies: “Well isn’t that what you’re supposed to do with shit?”

Arnie Cunningham (Keith Gordon) goes from being Rockbridge High’s preeminent dorkus malorkus to hepcat with the coolest whip in town. He rebels, starts swearing like a trooper, pushes his folks around (grabbing his father by the neck, Arnie spits “Keep your mitts off me, motherfucker”) and drops his pals. The character’s progression is basically Eugene from Grease into James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause with a sprinkle of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. The link to Nicholas Ray’s iconic own teen-rage classic is directly referenced in Arnie sporting a red suede jacket.

But what makes Carpenter’s film even more powerful is its electrifying reworking of the femme fatale figure of Romantic imagination. Put simply: Christine, the red-and-white 1958 Plymouth Fury, is one of the great seductress-monsters in big screen history, joining the likes of Joan Bennett in Scarlet Street, Ann Savage in Detour, Barbara Stanwyck in Double Indemnity and Jessica Rabbit in Who Framed Roger Rabbit. For Christine is John Keats’ ‘La belle dame san merci’, all shiny and chrome.

The scene in which she magically returns to original form, as if straight off the production line, after Arnie’s school bullies trash her with baseball bats – “One of them took a shit on the dashboard of my car” – is a thrilling seduction. The chilling synth music (a Carpenter speciality), use of off-screen sound (metal crunching), Arnie walking towards the camera and away from the car, then the absolutely note perfect zoom-in to his enthralled, expectant face – like somebody who knows they’re about to get laid.

“Okay, show me,” Arnie utters as Christine’s headlights burst into full beam – the lens flare shining with supernatural elegance – the score suddenly changing to a more bluesy-style mood, accompanied by a pulsing bassline and woozy saxophone melody. A magic moment of automobile erotica enough to give even JG Ballard the horn, Christine performs a demonic-mechanical striptease, her bewitching beauty and display of power hypnotising the poor kid.

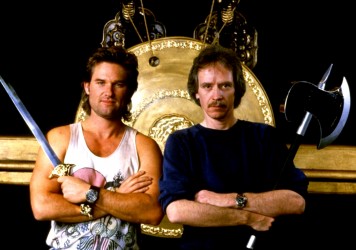

Arnie willingly hands over his heart and soul, and feels empowered by Christine’s beguiling influence and mystique. The unsuspecting fly in the black widow’s web tells concerned best buddy Dennis (John Stockwell) all about the workings of their grand pairing – his first true love – and how such passion has “a voracious appetite. It eats everything. Friendship. Family. It kills me how much it eats. But I’ll tell you something else. You feed it right, and it can be a beautiful thing.”

Published 30 Oct 2016

He may be all but retired from feature filmmaking, but traces of the genre director’s legacy can be found everywhere.

The cult director talks remakes, his love of early synthesisers and why nostalgia works in mysterious ways.

By Lara C Cory

Thirty years on, Sigourney Weaver’s iconic hero stands as a defiant symbol of gender equality.