The box office success of this 1991 drama forced America to view the crack epidemic from a different perspective.

This essay series looks at how five films released during rap’s golden era – King of New York, New Jack City, Juice, CB4 and Menace II Society – helped to shape American hip hop culture. We speak to filmmakers, rappers and historians to find out why these iconic works continue to endure.

Historically, no substance has changed the social dynamic of America’s inner cities more than crack cocaine. Many have noted how the drug spread like a plague in the 1980s, with crack’s high purity and low prices changing America’s drug supply chain overnight. And thanks to President Ronald Reagan’s infamous War on Drugs, just about everybody associated with crack was vilified by the mainstream media. Dealers, addicts, crack babies – the drug cast a “dark cloud” over America. But while the hardline media agenda was to demonise crack culture, America’s burgeoning hip hop culture was busy humanising those caught up in it.

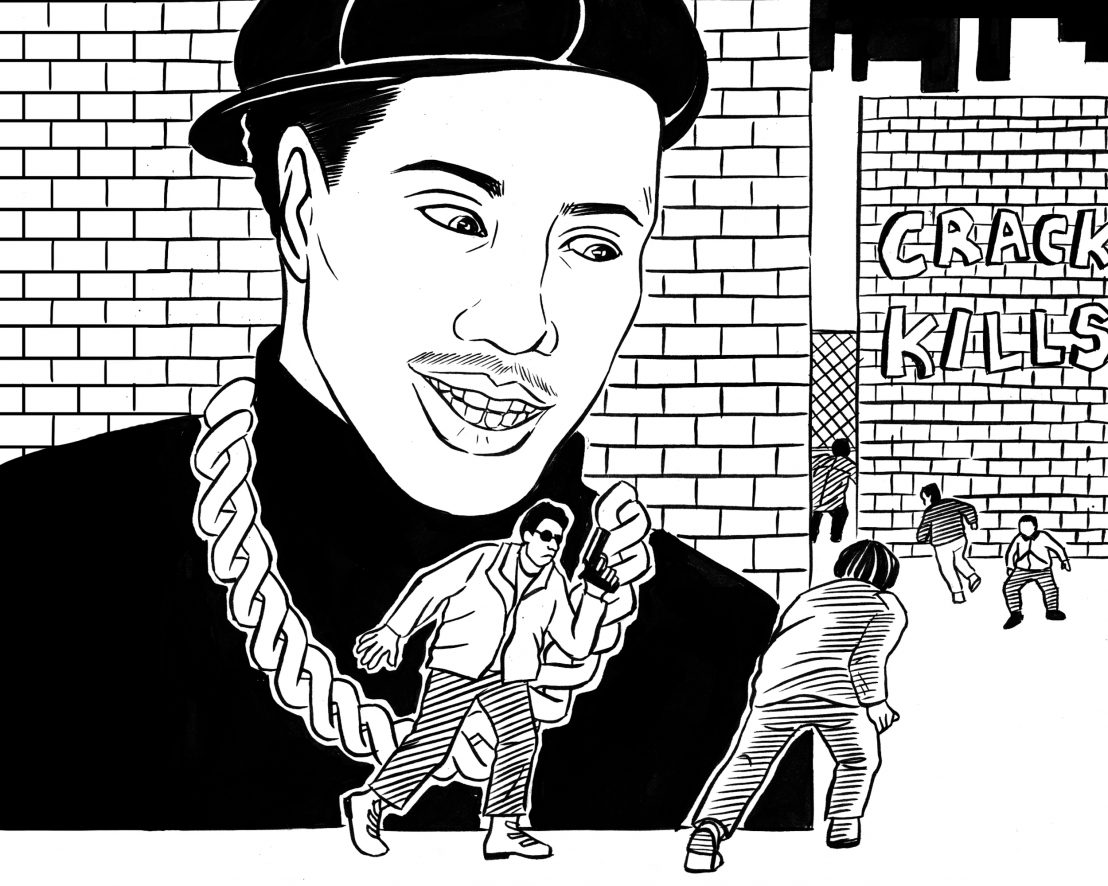

The rise of rap music went hand-in-hand with America’s crack epidemic, with some rappers warning against the drug (Kool Moe Dee’s 1986 song ‘Dee Crack Monster’ refers to the drug as the “devil”) and others painting its dealers as entrepreneurial figures (such as NWA’s 1988 single ‘Dopeman’). Director Mario von Peebles’ 1991 film New Jack City boldly did both, exposing how crack could lead to a path of opportunity as well as destruction.

The film documents the ascent of Nino Brown (a career-defining turn by Wesley Snipes), a rising Harlem drug pusher who quickly realises crack’s lucrative potential. He is hunted by Scotty Appleton, an undercover detective played by gangster rapper Ice-T, who wants to turn footsoldier-turned-addict Pookie (Chris Rock) into a weapon against Nino’s ‘Cash Money Brothers’ drug empire.

Thomas Lee Wright based the film’s original script on real-life ’70s heroin trafficker Nicky Barnes. However, after his SPIN article about Baltimore’s teenage crack gangs made waves, freelance journalist Barry Michael Cooper was approached to modernise the screenplay. “I was broke and working part-time at the docks loading trucks,” Cooper recalls. “George Jackson [an executive producer with Richard Pryor’s Indigo films] called the loading bay and asked me to take a look at this screenplay. I knew instantly I had to change the story from heroin to crack, and from then to now. The film needed to be a social document of what we were surrounded by.”

The film’s most emotive social commentary comes through Pookie, a twitchy drug phene who cries at how, “the crack keeps calling me and calling me!” Harlem-born Cooper reflects, “When I was 18, I had one foot in the library and one foot in the street. I thought it was cool to sniff coke, so I’d go down to 123rd street and occasionally buy off the dealers. Pookie was based on the return customers I used to meet. A lot of them were Vietnam vets: just good guys who couldn’t escape this chemical slave master that held so much sway over their lives.”

Rock’s brave performance asks audiences to empathise with crack addicts rather than dismiss them. His honest portrait of a black drug addict opened the doors for similar characters such as Andre Royo’s “Bubbles” in The Wire and even Dave Chappelle’s Tyrone Biggums, with the latter mirroring the livewire comedic energy Rock brought to the role. “I remember watching the dailies and the scene where Chris is in rehab and says ‘I don’t want to die’ had us all crying,” Cooper adds. “He should have been nominated for an Oscar, but the idea of a black film about crack terrified most of white Hollywood back in 1991.” New Jack City made over $50m at the US box office, showing a side of American society that mainstream audiences had rarely been exposed to before.

If Rock’s Pookie is the heart of the film, then Snipes’ performance as Nino Brown is its soul. Cooper wanted to write the character as a walking contradiction, a man whose heartening social consciousness (in one scene, he hands out turkeys to the poor) is only matched by his brutal ambition (he later boasts, “You gotta rob to get rich in the Reagan era!”). This duality, much like 1990’s King of New York and its complicated protagonist Frank White, intelligently mirrors the contradictions of rap music itself.

But look a little deeper and Nino is just as much a personification of the paranoia felt by black America during the 1980s. When he passionately declares, “Ain’t no uzis made in Harlem! There ain’t no poppy fields in Harlem! This is the American way!”, he points to hidden forces having had a hand in New York City’s crack epidemic. “Why is it all the drugs come from only one area in Harlem?” Cooper asks. “The film is about how there was a cleverly designed strategy behind everything going on from the drugs to the gentrification. We now know the CIA might have been involved in crack cocaine trafficking, and I wanted to also show that Nino was somebody created by a white power structure.”

There is a comic book quality to New Jack City’s visual style, with cinematographer Francis Kenny’s garish colours evoking Tim Burton’s Batman. When we first see Nino’s mansion, it is filled with gothic artwork and atmospheric candles. In fact, it looks more like the lair of Count Dracula than a Harlem drug lord. According to Cooper this was completely intentional: “What Nino is doing to his community is vampiric as he’s sucking the blood out of his people, only via crack. We wanted where he lived – from the furniture to the candles – to show he was a monster just like Dracula.”

Yet even if a cautionary tale around the “monster” of Nino Brown is apparent within New Jack City, its impact on hip hop culture has been anything but cautionary. As rapper Daryl “DMC” McDaniels, one third of the legendary Queens rap group Run-DMC, puts it: “The film kind of made everyone think drug dealing was a good thing. Thanks to Nino’s confidence, style and swagger, everyone wanted to be like him. They loved him and all these drug dealing rappers were inspired by him. Nino Brown became the black Scarface! He gave the drug dealers a black ‘hero’ to look up to. That was ill.”

Cooper interjects: “Look, Nino dies at the end of the movie because it’s a cautionary tale. I’ve heard some people have recut the film so Nino doesn’t die – it’s a weird feeling man, but I’m just glad people still have so much love for a movie that’s nearly 30 years old.”

From Jay-Z to 50 Cent verses, New Jack City remains one of the most referenced films in rap history, its legacy most evident in Cash Money Records, a record label whose blockbuster roster of artists includes Drake, Lil’ Wayne and Nicki Minaj, and whose name and company logo is an obvious ode to Nino’s Cash Money Brothers – “Lil’ Wayne owes me a cheque!” jokes Cooper, who is currently writing a book called ‘The Diary of Nino Brown’.

Although New Jack City may have unintentionally glorified drug dealing to the hip hop community, Cooper believes that the film’s true message has been amplified by the current administration’s approach to tackling America’s drug problem. “The way Trump is being oppressive towards the black and Latino communities is just like the Reagan era, and it means antiheroes like Nino Brown will only rise again. It’s sad that that’s the case, but it is what it is.”

Published 14 Mar 2018

By Thomas Hobbs

How Abel Ferrara’s brutal 1990 gangster flick captured the imagination of the hip hop community.

By Thomas Hobbs

With its thrilling performances and damning anti-gun message, Ernest Dickerson’s portrait of America continues to touch a nerve.

By Thomas Hobbs

How a low-budget Chris Rock comedy exposed the absurdity of gangsta rap.