Directed by Andy Warhol’s lover Jed Johnson, a former Factory floor sweeper-cum-film editor (Flesh for Frankenstein) and interior design guru, Bad focuses on the exploits of a hairdresser who operates a hair removal service from her house, while simultaneously hiring out female assassins to perform a vast array of twisted assignments as a means of earning extra cash.

As with every other film made by Warhol’s production company, namely Paul Morrissey’s Flesh, Trash and Heat, Bad is traditionally discursive with the addition of a series of digressive subplots principally contrived to shock and exasperate the discerning viewer. The difference between the film and those earlier works is not only the change of director but also the bigger budget, which allowed Johnson to hire industry professionals.

In an opening scene that feels stripped from a John Waters picture, Cyrinda Foxe’s bleached-blonde bombshell, RC, struts through a drugstore with the voluptuousness of a bedraggled Jayne Mansfield caricature. She steals a dirty old man’s half leftover burger before blocking a toilet with tissue and trashing the joint. We’re introduced to the film as the toilet and its contents overflows. As the perfect curves of RC’s backside are followed down a street and she is wolf-whistled by lecherous bin man, it becomes clear that Bad has already subverted our understanding of the buxom heroine and by extension women in cinema at large.

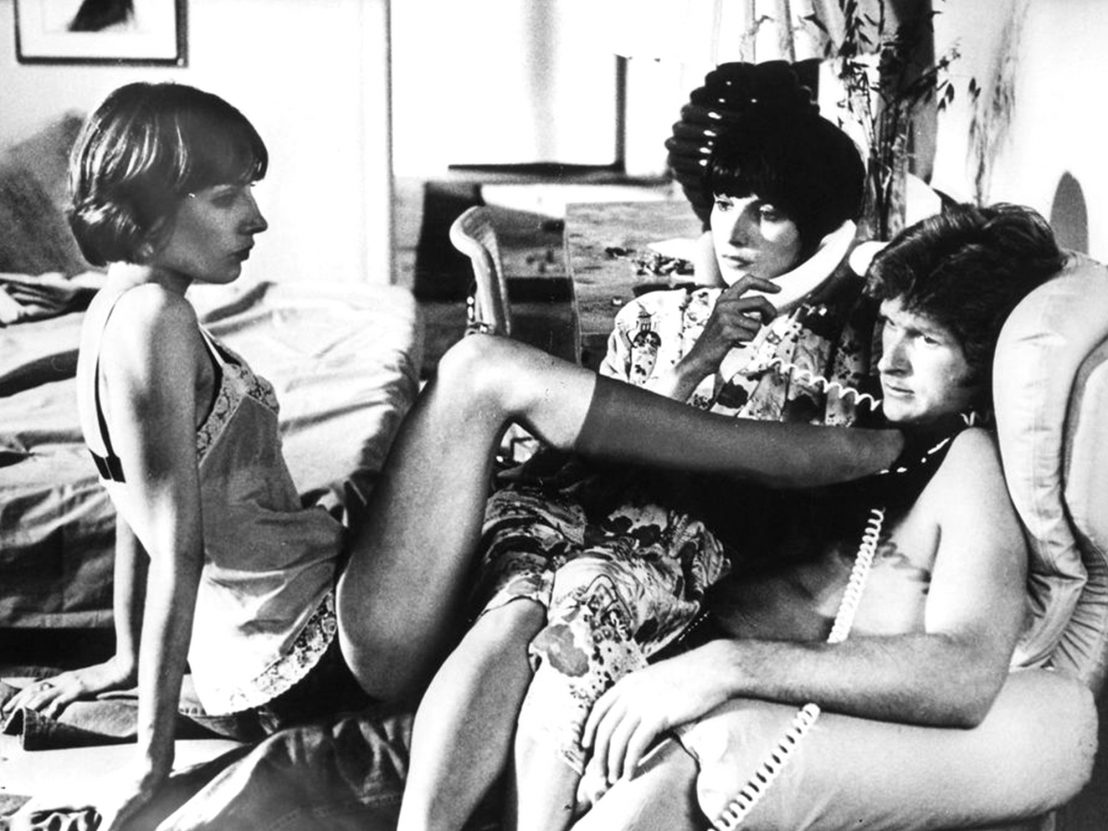

Warhol movies were among the first to objectify the male form, as Joe Dallesandro’s quiet and mostly naked performances attest to. Dallesandro turned down the role of LT in Bad, the part eventually going to lookalike Perry King, who looked decent enough with his shirt off and could act dumb while handling demonstrative dialogue.

Intriguingly, the film’s only sex scene is orchestrated by a horny woman after flicking through a porn magazine. A couple of passionless jerks later, she expresses her disappointment and leaves LT defiled in a shower of cutting and sarcastic remarks. Where Little Joe owned the Paul Morrissey trilogy, Bad very much belongs to the women.

Here we have a powerful and mercilessly angry hit-harem, characterised chiefly by their actions. Heartless and hungry for money, there is literally nothing that these extreme feminists won’t do for a pay cheque. And we’re not talking Pretty Woman – more Shirley Stoler in The Honeymoon Killers, fed after midnight and multiplied. Conscience is non existent in this brood of audacious ladies.

Caroll Baker excels in the lead as hitman king pin Hazel Aiken, whose ability to remove “650 hairs an hour” and run a murder-for-hire business is ignored by her vapid and useless husband. Her pungent one-liners are delivered with laughable soap opera histrionics that blend congruently with the rest of the cast. Although Hazel herself never knowingly commits a single crime within the film, her knowledge of the homicidal assignments and the flippancy with which she delegates tasks to her girls makes her so much more chilling than, say, Kathleen Turner and her darkly comic, Hazel-inspired, Serial Mom.

In contrast to Hazel’s total lack of humanity is Mary Aitken, the grouchy daughter-in-law played by a scene-stealing Susan Tyrell. For the majority of the film, Mary sits shaking her head in disbelief at the actions of everyone around her. “People are so sick,” she tells LT, “The more you see ’em, the sicker they look.” Mary is the sweetest anomaly. Her face is constantly on the verge of tears, her tone emotionally heightened, yet she is the only character in the entire film with a relatable sense of morality, which suggests that the film is not set in modern day Queens but a malevolent and inhumane alternate universe, an intrinsically “bad” place where human nature is overthrown for the sake of money and the illusion of a vacuous and easy life.

Children and babies play a significant role in Johnson’s film. Serge Eisenstein’s silent classic Battleship Potemkin laid down the gauntlet in terms of tension and large-scale action when an unattended baby makes the long journey down the Odessa steps. One of the most famous sequences in the history of cinema, the scene has been homaged many times before and Bad, with its subversive agenda, gamely obliges – without warning, a baby is tossed from a multi-storey building where it hits the city street below with hideously gruesome aplomb. Pushing the boundaries of taste and black comedy, a mother then threatens her son with similar consequences if he doesn’t behave himself. It’s very funny, but with a splattered baby laying before you, it’s impossible to even crack a grin.

Infanticide is used ironically, of course, not solely to shock the timid viewer but to satirically shake America while providing comment on the issue of abortion, an issue insouciantly discussed during the film. In fact, it’s worth noting that in there is no such thing as a happy mother in Bad. Children are routinely chastised, beaten or murdered for nothing more than being a disturbance. Maternal instinct is aggressively rejected by all of the women in this universe.

LT’s paternal instincts come under scrutiny when he is hired to murder an autistic child (the child’s mother initially requests a woman for the job). Occupying the role of the objectified male, however, he fails to carry out the task, thus highlighting both his already evident emasculation as well as reflecting the pro-life ideologies of the misinformed male. Rendered pathetic in this world of empowered women, he carries the child into its parents’ bedroom and yells “Do it yourself!” Not everything goes according to Hazel’s masterplan, then, as the incompetent actions of others and a callous racist slur lead to her melodramatic final breath.

The film’s curious footnote is delivered in its closing scene when Mary crosses over to the dark side. A baby is again used to signify this shift. Her son, who has been held so tightly under her arm throughout, falls to the floor as her grip loosens. With the evil matriarch dead in the sink, Mary clasps her mother-in-law’s lipstick in one hand and her earrings in the other. “Looks aren’t everything,” she says with the awkward self-awareness of a child in a school play.

It’s fascinating to envisage Mary’s next move beyond the end credits, like the Witch from The Wizard of Oz, she is left with some wicked shoes to fill – but could they ever fit the film’s only vestige of mercy? Bad relishes flipping gender roles, underlining in its last line the fact that there is so much more to a woman than just her image.

Other than Jonathan Kapland’s all-girl western, Bad Girls, or F Gary Gray’s Set It Off, it’s hard to think of another film that interchanges gender roles with similar visceral impact. As such it’s disappointing that Bad is the only film from the last 40 years to deliver a plethora of female characters who openly and violently reject social conformity. It should not be buried or forgotten, because as nasty and as rotten as it is on the surface, Bad is a vital cult treasure that’s ripe for a major reissue.

Published 21 Feb 2017

Anna Biller’s The Love Witch offers a playful take on a genre dominated by male perspectives.

The Pope of Trash reflects on his controversial career ahead of the re-release of his black comedy Multiple Maniacs.

By Thomas Hobbs

I was skeptical about pairing The Wizard of Oz and Pink Floyd, until I decided to put the fan theory to the test...