Known variously as the father, godfather and god of manga, Osamu Tezuka revolutionised comic books in Japan with influential series like ‘Astro Boy’, ‘Kimba the White Lion’, ‘Black Jack’ and ‘Phoenix’. In 1963 he founded the company Mushi Productions and created an animated version of Astro Boy for television – the first popular Japanese series to deploy the aesthetic that would become associated with anime, and the first to be broadcast overseas (and dubbed into English).

In the late 1960s, Tezuka conceived and initiated a new series of anime features, known collectively as Animerama. These films were to look to the past (whether historic or mythic), were to be formally experimental, and were to be aimed, with their erotic content, at an adult audience.

Though the first film made under the Animerama umbrella, Tezuka’s A Thousand And One Nights, was a box office hit in Japan, the other two, Tezuka and Eiichi Yamamoto’s Cleopatra and Yamamoto’s Belladonna of Sadness, were commercial flops, leading to the collapse of Mushi Productions. Part of the problem was their innovation, which is never easy to market to audiences looking for more of the same. The demographic of previous animated features had been children and families, and there was no pre-existing market for the bawdier content of the Animerama features (Ralph Bakshi’s much more successful Fritz the Cat came out two years after Cleopatra, but was directly plugged in to a very specific American counterculture).

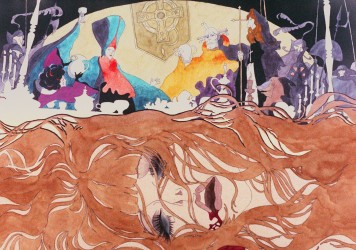

The lengths, too, of A Thousand and One Nights and Cleopatra – each clocking in at around a hefty two hours – were without precedent for animation at the time. The last of the three Animerama titles, Yamamoto’s Belladonna of Sadness, is now the best known internationally, not least because, after a very limited theatrical rerelease in the US in 2009, it underwent a 4K restoration in 2015 and enjoyed a new life (and a critical reassessment) in cinemas. Yet, so many decades after their initial box-office failure and years in the wilderness of cinematic oblivion (the original English-language dubs are apparently lost forever), Tezuka’s first two features also merit new eyes and new attention, and are now welcome precisely for their refusal to fit the cookie-cutter model of animation from their own time.

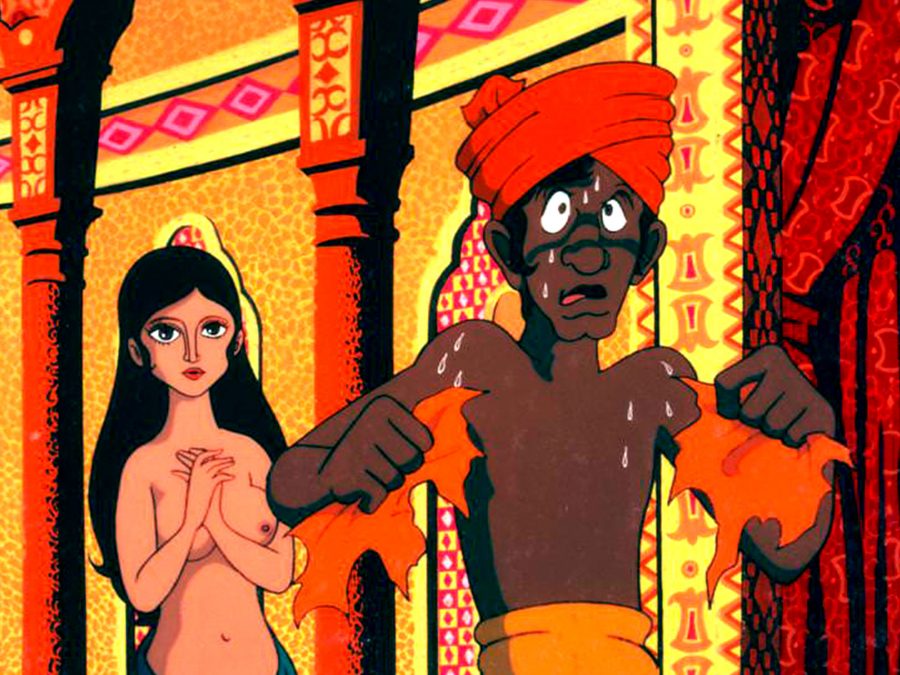

First, a corrective. Despite their reputation as ‘X-rated’ animation, these films are not in the least bit pornographic. The dialogue can be on the blue side, and women’s breasts are regularly bared, but Tezuka is extremely coy about showing the genitalia of either sex, and the sex act itself is reduced to curvy, multi-limbed abstractions or visions of flowers with gaping tunnels. Visually this is the very softest of soft core, even if these story worlds are populated with the priapic and the promiscuous, and if part of the message of Cleopatra, encapsulated in its closing theme song, is that “We are all monkeys” driven by our animalistic urges.

A curious example of orientalism done Japanese-style, A Thousand and One Nights certainly draws from the Middle Eastern corpus of folktales from which it has taken its name, but also conflates and confounds them to delirious effect, while sexing them up no end. Aladdin (here called Aldin) merges into, and is expressly confused with, Sinbad, and undergoes all manner of adventures by land and sea. Tezuka’s merging of traditional animation, still paintings, modernist design and real footage makes for an anything-goes mode of fable where magic and the unexpected always seem possible, and where the very forms that constitute this story world are presented as unstable.

Meanwhile, the inclusion of anachronistic items (the Caliph has, among his rare, exotic treasures, what look like a television set and an automobile; a towering edifice, as it collapses, reveals a label that self-referentially if cynically reads “Made in Japan”) further destabilises our grip on Tezuka’s fairy tale confection. All the while, a trippy colour palette and Isao Tomita’s psych-rock score ensure that the film’s story belongs as much to the late Sixties as to some mythic period in and around ancient Baghdad.

If Aldin, as a humble itinerant water vendor persecuted by the wealthy and powerful, at first seems relatable, by the film’s final act he has acquired riches and the caliphate for himself, and we see the power go right to his head as he tests “how far a king can go” with a series of arbitrary and destructive proclamations. This concern with the corrupting dynamics of power is a central theme in Cleopatra too. which – perhaps uniquely among the many film versions of the Egyptian Queen’s tragedy – opens with a spacecraft hurtling across the stars. This unexpected coupling of sci-fi future and historic past is typical of the film’s slippery approach to time.

For in a city of the future, as caviar is served with champagne (from an 1849 vintage), Jiro, Maria and Hal are informed by their chief that guerrillas from the planet Pasatorine are resisting the Earth’s ‘Universe Plan’, and have their own ‘Cleopatra Plan’ prepared to assist their rebellion. In order to determine what this mysteriously named plot might be, the trio are sent back in time via prototype “psycho teleporters” which enable them to inhabit the bodies of, respectively, Caesar’s slave Ionius, Egyptian ‘city girl’ Libya, and Cleopatra’s pet leopard Rupa.

Meanwhile, Cleopatra is undergoing her own body swap, transformed by a magician from a plain princess to the most beautiful woman the world has ever seen – all so that she can murder first Julius Caesar, then Marcus Antonius, and finally Octavian. Caesar, too, seems to harbour more than one personality in his body – not just because he is a complex, multi-faceted character but also because he is expressly schizophrenic – and his roles as patriotic general, passionate lover and devoted husband seems mere performances, leaving everyone confused who ‘the real Caesar’ is.

Likewise Cleopatra is forced to play the part of seductive assassin, and really just wants to be loved for who she is, so that she finds her own allegiances – no less than Jiro’s, Maria’s and Hal’s – being repeatedly tested. All are caught in time’s ebb and flow, in a story set across two very distinctive time periods where the human history of erotic and territorial conquest seems nonetheless doomed ever to repeat itself.

The tone here is mostly comic, but the montage introducing us to the Roman occupation of Alexandria casually sets depictions of mass torture, rape and slaughter (no doubt echoing what Earth later has in store for Pasatorine) alongside goofy upskirt gags, all in a manner that lays out the gravity of the themes underlying the scabrous jokes. Meanwhile, Cleopatra deploys surreal anachronisms and transnational forms to suggest a continuum between disparate eras and cultures.

It makes perfect narrative sense that Ionius, using Jiro’s future knowhow, can fashion grenades and a revolver during the Late Republic of Rome, but far less sense that Caesar’s triumphal return to Rome should be accompanied by Toulouse Lautrec’s can-can dancers, Botticelli’s Venus, a winking, topless Mona Lisa, Dalí’s burning giraffe, Bosch’s hellish monsters, Picasso’s abstractions and various Pop Art figures; or that a self-conscious Antonius should call his diminutive penis a “compact car” compared to Caesar’s which was “a dump truck that required a special licence”; or that an Arab Airlines plane, a plummeting airship and even a floating Apollo command module should all be spotted during the naval Battle of Actium.

There are even references to Tezuka’s own past (future) art: Rupa is seen using ‘White Lion’ toothpaste; and when, as Ionius is about to be killed in the Coliseum, Cleopatra calls for a hero to “save that man!”, there is a cutaway to Astroboy himself flying through space. Meanwhile, the murder of Caesar in the Senate is presented as a stylised nōh play, complete with flute-and-drum score and bamboo trees painted on a screen backdrop.

The point would appear to be that the drama of love and power played out here in Rome and Egypt – and repeated in the conflict between Earth and Pasatorine – sends its echo across time, space and art in every era of humanity. It is a satirical, and rather unflattering, depiction of our species (here renamed ‘Pithecanthropus Guerrillatus’ in song), collapsing the distance of Ancient Rome into a non-evolutionary, retrofuturist, postmodern timeline that includes and implicates us all. Third Window Films’ new double-set is worth getting for this astonishing UFO alone – but A Thousand and One Nights, both simpler and similar thematically, rounds things off nicely.

A Thousand and One Nights and Cleopatra are released as a double-feature in the world’s first ever Blu-ray and remastered DVD edition by Third Window Films on 18 June.

Published 18 Jun 2018

By Giacomo Lee

Patlabor 2 and other classic-era sci-fi show the past, present and future of Japan’s capital.

Rare shorts from 1917 to 1941 are now streaming in celebration of 100 years of anime.

Look out for Eiichi Yamamoto’s transgressive epic from 1973, Belladonna of Sadness.